By Lance Hodgins

For 40 years the Moorooduc Quarry was the main source of stone for the roads of the Shire of Frankston and Hastings. It nearly didn’t survive past its second birthday.

The ridge on the northern edge of the Moorooduc Plains held a hard, high quality stone. It was first exploited in the late 1880s by David Munro & Co who found it to be perfect ballast under the new railway lines he was building to Stony Point and Mornington.

After this, the quarry lay idle – the motoring age had yet to make its mark on the landscape with its need for roads. It was not until well into the twentieth century that cars became more common and local governments realised that they would face an ever-expanding road network to build and maintain.

For most of the Peninsula, these needs were being met by several private quarries. Not so in the north, where Frankston Riding councillors saw that their requirements would soon outstrip the existing supply from the quarry in Cole’s Paddock. They eyed the old Moorooduc one, which sat on 400 acres of timbered land belonging to the Stenneken family. Money was tight, however, and when the Great War rolled around to demand different priorities, plans for a Shire quarry were put on hold.

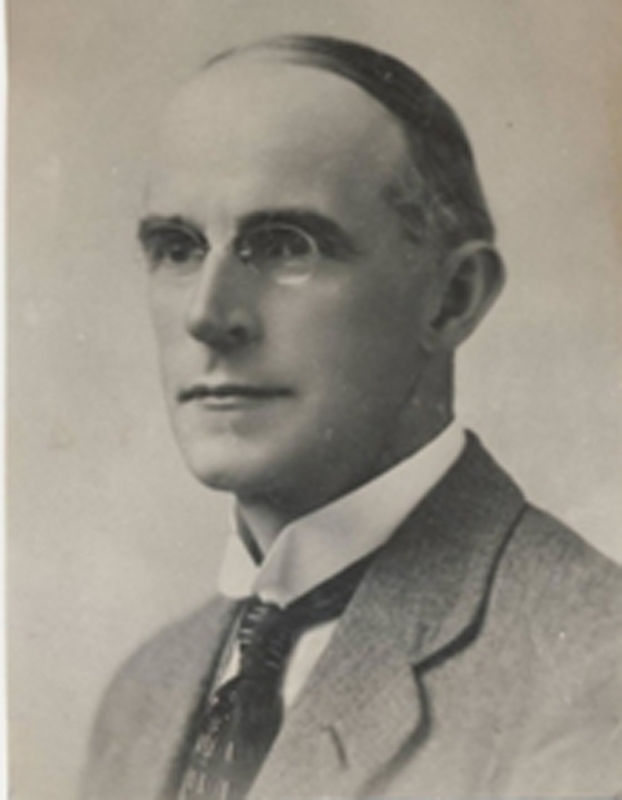

Frankston Shire Engineer A. K. T. Sambell

The Good Deal

Finally, in 1919, the land became available for purchase and the Council made its move. On top of the purchase price, Council would have to borrow £6,500 (about $3 million today) to buy and instal the necessary equipment.

A public meeting was held to explain the economics of the project. A 50 feet face of high quality rock could be quarried immediately. There was a twenty-year timber supply to feed the steam engines. The newly-formed Country Roads Board would guarantee a steady market, and pay a bonus for locally crushed material. Council calculated that it could halve its road construction costs if it could provide its own stone.

By December 1920 a second-hand plant had been erected and on Friday 7 January 1921 William Calder, chairman of the Country Roads Board, performed the official opening.

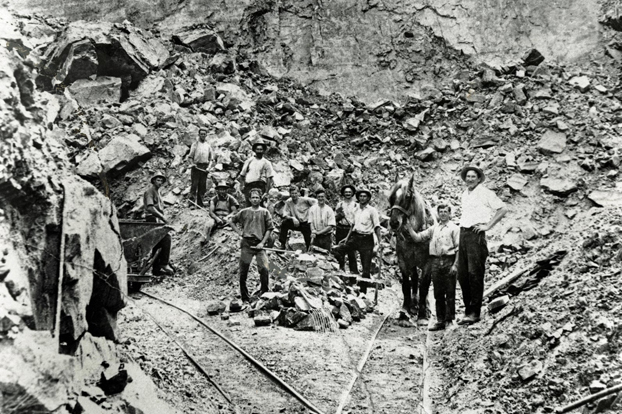

Members of the Shire of Frankston and Hastings Council on an outing, 1923

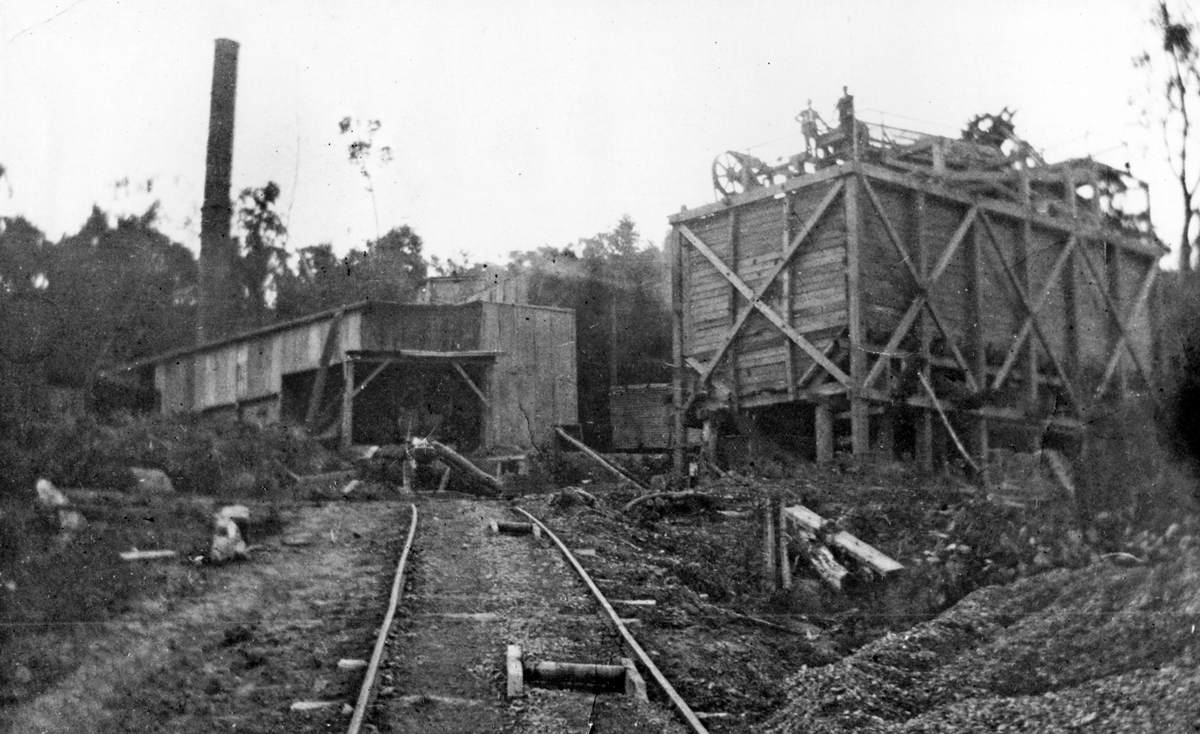

The new works were impressive. The crushing plant was worked by a 90hp duplex steam engine, and the boiler was 30 feet long and weighed seven tons. The immense flywheel was a whopping 14 feet in diameter and, with its shaft, weighed another seven tons. It had been constructed by the same firm which had built both Victoria’s first locomotive engine and the government steamer Lady Loch.

The two Jacques stone-breakers could produce 180 cubic yards a day. Water from a hill-top reservoir was superheated before reaching the engine, thus ensuring extra steam pressure. The stone was then graded by size and delivered to storage bins, which emptied into trucks on a tramline which led to the railway siding lower down the hill.

Overall, the plant was regarded as a credit to the Frankston Shire Engineer A K T Sambell, who designed and supervised its erection. Sambell was a most capable engineer. He went on to establish the Peninsula and Naval Base water supply network before moving to Phillip Island, where he ran the Westernport Shipping Company and became the local Shire’s first president.

The quarry was initially managed by a father-son combination, Frank Jolly snr and his engineer son Frank jr, who were experienced quarry operators from Glenrowan. Most of the workmen, however, were new to the job and the first few months saw some minor teething problems.

Output was fairly steady for the first two years, but questions were starting to arise inside the Shire Offices over its profitability. In 1923, when one councillor suggested they visit neighbouring quarries for advice, Cr Longmuir stated that this would not improve matters as the quarry had been put in the wrong place to begin with.

“They should put a charge of dynamite under it, blow it into the gully and start all over again,” he said.

The Moorooduc Quarry in disrepair

Towards the end of 1923, increased wages were being blamed for the lack of profits and it was suggested that the quarry double the price of its product “in order to pay its way”. The Shire embarked on three months of financial soul-searching and when the plant closed down over summer for a general overhaul and repairs, some councillors were even asking if it should ever be re-opened.

The quarry cost money to stay open, it was argued. Yet, on the other hand, if it closed there would be insufficient screenings for the Shire’s tarring program and roads would slip into further disrepair and create a future expense of their own.

“A mountain of stone badly managed.”

Enter one George Nelson of Baxter – a quarryman with Broken Hill experience and no hesitation in coming forward and speaking his mind. In fact, his comments were scathingly blunt.

To him, the quarry was “a mountain of stone badly managed. It had run for four years at a loss of £16,000. The engine was worn out, the crusher jaws were getting worn out … and so were the ratepayers who were asking when the profits are going to come.”

He claimed that the quarry should have shown a profit right from the start. The rock was excellent and there was nothing wrong with the machinery. It was simply being run poorly. He made it clear that he was prepared to undertake the working of the quarry if the present system was adjusted to meet his ideas, which he outlined in detail, and he guaranteed to make it a success.

“With better management, I can turn this white elephant into a gold mine, and the ratepayers will not be ashamed of it as they are today. In six months’ time I could be turning a profit of £10-£15 a day, and possibly double that.”

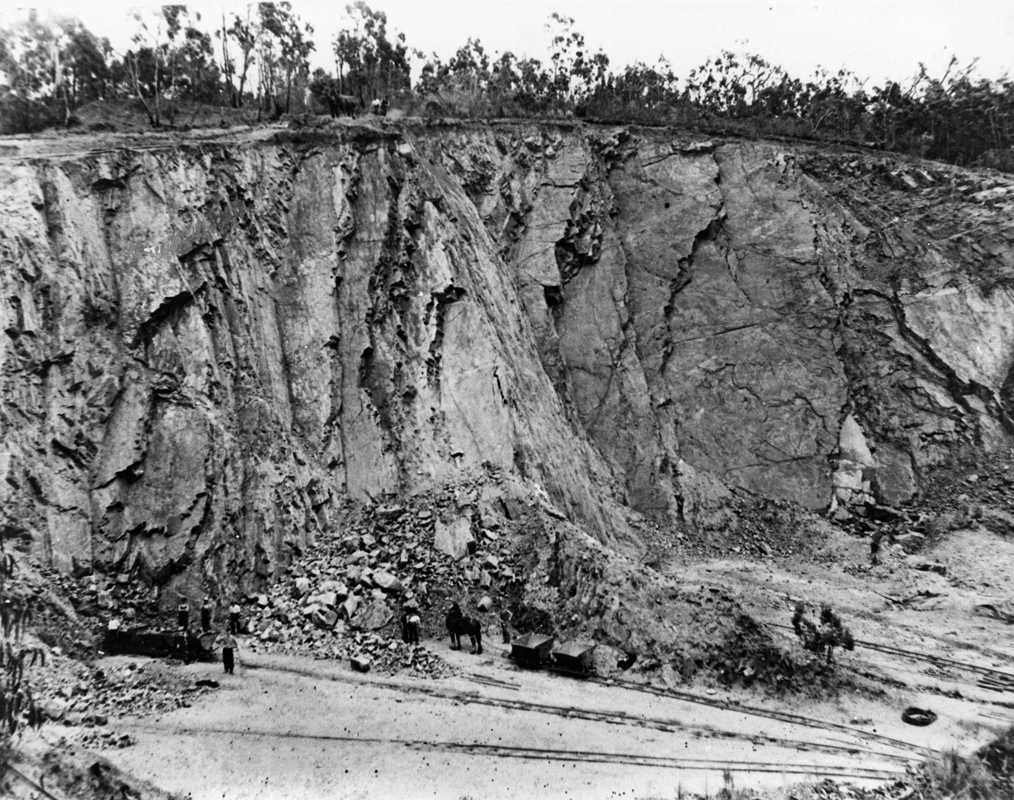

The quarry in 1935

Despite his forthright comments, Nelson failed to convince the Councillors and he was passed over for the position of manager.

By April 1924 the new boss, Chester Pullen, was able to report steady production – but at a heavy cost: several workers had to be retrenched. When orders declined in the following month, he was forced to put off three more workers “of the type that would be hard to replace when business picks up again.” It was clear that something drastic needed to be done to achieve a profitable output.

Nelson fired another salvo at management: “Any responsible person should not be allowed to stop there if he could not show improvements and a profit. If he can’t show from £10 to £18 per day by the end of six months then the council should remind him that the ratepayers need a fair deal, and it would be better if he looked for another job.”

This drew a spirited reply from a Mr W J Hills who had worked at the quarry for almost two years under four different foremen. Hills disputed Nelson’s claim that the crusher was often lying idle waiting for a supply of stone and he explained that the muckiness of the stone was due to the wet weather. He defended the present manager, who “had 14 years’ experience in open-cut and underground mining and could in no way be called a learner.”

Nelson replied that it was the workers, and not the manager, who he had called “learners”. He maintained that the mucky stone was the result of poor quarrying and that if better quality had been produced then the stone would “sell itself” and Council would have no trouble in getting orders.

Back to work at the quarry

All of this was happening at a time when the Council was extremely short of cash and they were getting desperate. In an attempt to save money, even the Shire Engineer’s permanent position was axed and the “founding father” of the quarry, A K T Sambell, found himself working in the position of consultant engineer on a daily rate.

In September of 1924 the quarry shut down for maintenance and, once again, the councillors argued about its future. Orders were drying up as a result of the poor stone and private quarries were having a field day. Some councillors feared that if the quarry was closed now it would never re-open.

The Frankston Comfort Station

Quarryman Hills took this opportunity to attack Nelson for having given “cheap advice to the ratepayers”. He warned that “Nelson would cull workers to the point of no return. He was only after the £8 a week manager’s salary and would promise all sorts of good things to get it. His figures just don’t add up. It is clear why the Councillors had not employed him 12 months ago.”

The quarry remained closed whilst Council continued to discuss its future. With every week it remained closed it cost £34 – made up of £22 bank interest, £8 manager’s salary and £4 assistant’s salary. Carrum Shire were approached to lease, buy or be a partner in the quarry. After one inspection, they decided to give it a miss.

Cr McCulloch moved that the quarry reopen under electric power and pushed for a sales agent to gather fresh orders. Cr Pratt cautioned that the quarry at that moment seemed to be poorly managed. The head of the Shire quarry committee, Cr Wells, argued the quarry could return to being worked properly once 500 yards of rubbish was removed. The vote was finally carried and the quarry was reopened.

The stables at Cruden Farm

One last roll of the dice

George Nelson had one last chance – he arranged a meeting of all interested ratepayers and councillors. On a Saturday afternoon in November 1924 a small group gathered at the quarry, but some councillors were conspicuous by their absence. Only Cr Wells and Cr White were present, along with one former councillor and eleven other gentlemen.

The visitors saw neglect all around them. The tram line was almost covered in mullock and it was accumulating rust. The line was kinked, sleepers were hanging in mid-air, and observers wondered how the trucks could stay on them. Plenty of good stone could be seen but careless stripping of the overburden had left it covered with poorer stone and hard to get at.

Nelson addressed the small assemblage: “This quarry has been worked for three years and not one improvement has been made. At the end of the first year there was a loss of £3,000 and at the end of the next year there was a further loss, and still no improvements. The quarry has shown a loss of £10 per day whereas it could be made to show a profit of £10 per day.”

The old explosives store

Nelson’s talk was not idle criticism and he had definite plans for improvement. He would build a 300 yard line of bins so that 10-15 rail trucks could be loaded from chutes at the same time, by gravity rather than a steam-driven winch. He would also strip the overburden using horses and scoops instead of the archaic wheelbarrows and shovels and thus follow the better seams of rock.

Nelson related that twelve months ago he had inspected the quarry with the Shire President and Engineer who both seemed satisfied that he knew his business. They told him that he could manage the quarry when he finished his current job but, within a fortnight, he learned that there had “been a re-shuffle” and he was no longer required.

“Can the councillors tell me why I was not given a chance to prove myself? Where were my improvements wrong?” he asked.

“If the councillors thought that I did not know my work, I am now convinced that they do not know theirs. They have one of the best quarries in Victoria to be worked by gravitation, but nothing there is worked by it. There were plenty of improvements to be made but they have stumbled over them for years and been left with one of the dirtiest worked quarries in Australia. And that is praising it!”

Cr Wells, as chairman of the quarry sub-committee, made a couple of conciliatory comments before offering Mr Nelson a vote of thanks for his trouble in arranging the group’s visit. And everyone went home.

A new start

Within six months, however, the quarry was converted to electricity and the Shire threw its support behind other improvements.

A new compressor and plant were installed and in 1927 the official opening was performed, once again by William Calder, Chairman of the Country Roads Board.

The quarry went on to survive the Great Depression of the 1930s. After an initial slump, it successfully operated two shifts a day and every month over 1500 cubic yards of Moorooduc stone were being poured onto local roads.

A truck was purchased which could deliver stone to the Country Roads Board at four pence a ton per mile cheaper than any other source in the State. The truck made a profit of £1,000 in its first year and soon led to the purchase of others.

An aerial view of the quarry as it is today

The Second World War saw the quarry hit hard by a nationwide shortage of labour but it was declared a protected industry and managed to avoid closure. In April 1945 accusations of ineptitude and inexperience led to an inspection by a gathering of journalists who were given a candid view of the operations. Their reports in the local press put the criticism to rest.

They found that the foreman, Mr Shimmen, had 30 years of quarrying experience. Mr Johnson, the leading hand, along with Charlie Upton and Jim Holley, had all been there for some time. The Shire Quarry Committee chairman, Cr Wells, was also serving as quarry manager and saved the Shire £8/10/- a week in wages. Before he was elected to council, he had been a road contractor and quarried his own metal.

The visitors found the works to be in excellent condition. The plant had been overhauled and the crusher recently repaired. A new face of stone had been opened and output had risen to 40 cubic yards a day. The plan was to remove the plant and reconstruct it closer to this new face of stone. The liability of the quarry in its early days had been £26,000 – this was now down to £4,000.

The stone itself was widely popular and used in several landmark buildings of the district.

One example was the stable and garden walls of Dame Elizabeth Murdoch’s Cruden Farm. Another lasting memorial stands on the Nepean Highway in the middle of Frankston – the Comfort Station – built and faced in Moorooduc stone in 1941. Parts of Frankston State School used the decorative stone as did most of the houses in Gull’s Way, Mt Eliza.

Persistent flooding, however, caused the quarry to close in 1961 and twelve years later it was designated a flora and fauna reserve by Frankston Council. Today, several species of eucalyptus and acacia dominate the Reserve and there is an abundance of orchids, native grasses and wildflowers. Many species of birds breed there.

There are several walking tracks, along which the ruins of an old explosives store can be seen – one of the few remnants of this once important site.

Footnote:

This is a chapter from “Tiffs over Time”, a collection of arguments from earlier times on the Mornington Peninsula. Copies are available from the author for $20 plus postage if necessary. Contact Lance on 0427 160 892.