By Ilma Hackett, Balnarring and District Historical Society

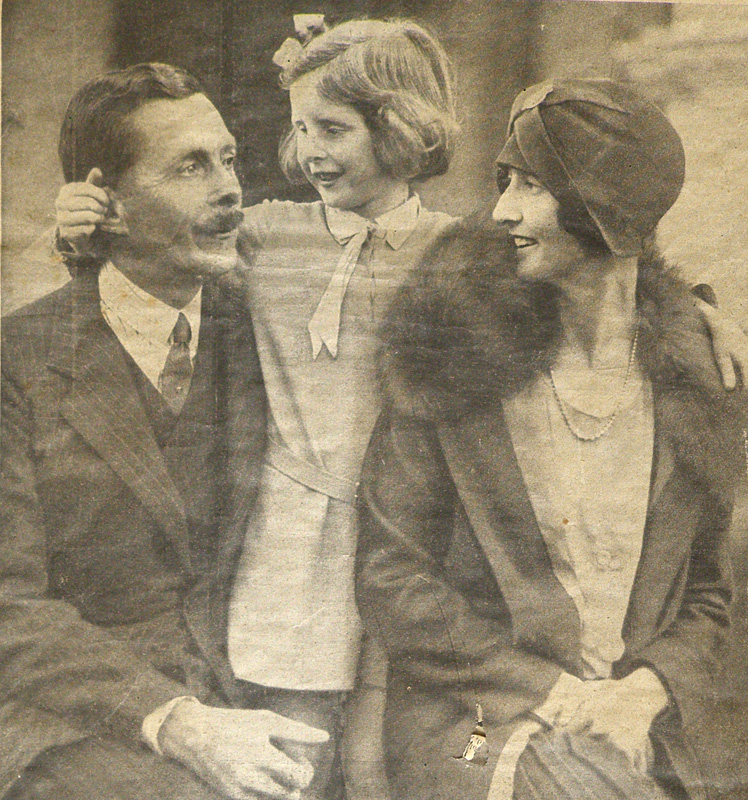

When Victoria’s new Governor walked down the gangplank of H.M.S. Cathay on a ‘cheerless’ winter day in 1926 a ripple of surprise ran through the dignitaries waiting to meet him. Tall and athletic, he looked so young! The Right Honourable Lieutenant–Colonel Arthur Herbert Tennyson Cocks, Sixth Baron Somers of Evesham, otherwise known as Lord Somers, was thirty- nine years old. He was a military man, a war hero with a string of letters after his name – KCMG, MC, DSO, LOH (Knight Commander of the order of St Michael and St George, Military Cross, Distinguished Service Order, Legion of Honour). With him was his attractive, thirty-year old wife, Finola, Lady Somers, and their three-year old daughter, Elizabeth. The new vice-regal couple were welcomed enthusiastically. Boy Scouts formed a guard of honour on the pier while the road into the city was lined with school children. It was a fitting welcome for a couple who would do much for the youth of the state during their time in Victoria.

The Duke of York’s Vision

The following year the Duke of York (later George VI) visited Australia for the opening of the new Parliament House in Canberra. Whilst in Victoria he shared with Lord Somers his ideas behind the annual camps he had initiated in the U.K. These aimed at bringing together the youth from different levels of society to live and play together on an equal footing. Disturbed by the wide-scale industrial unrest that followed the First World War, the camps were an attempt to foster in young people a sense of co-operation, comradeship and camaraderie. Lord Somers was much taken by the idea and discussed it with others involved with youth groups, in particular with Dr Cecil McAdam. ‘Doc’ McAdam was District Scout Commissioner and honorary medical officer to a number of youth groups, including Toc H. an international movement that, through acts of service, improved things for others. He was a brilliant youth leader and organiser. The two men shared similar ideals, believing in service to God, king and country and both had served in the First World War. Their plan was to bring together forty boys from public schools and forty boys from industry to participate together in a camp to be held at the personal invitation of the Governor. The boys, aged between seventeen and nineteen, would spend a week on a summer camp to be held in mid- January. By living, playing and working together on an equal footing it was hoped that social barriers between the two groups would be broken down and lead to greater understanding. So enthusiastic was Lord Somers that he contributed £450 of his own money towards making the camp a reality.

The First Big Camp

The Scout Camp at Anglesea was chosen as the site for the first Lord Somers Camp in 1929.

This was home to Harold Hurst’s 1st Otway Foresters’ Troop. Hurst was Scout Commissioner of the Geelong area. A quiet man but an excellent leader and organiser, he was well-liked and respected by the scouts who called him ‘Boss’. Boss Hurst was the obvious choice for Camp Chief.

The site was in a secluded bushland setting by the Anglesea River and located close to the surf beach. Here the boys, guided by camp leaders, could learn bush lore, enjoy swimming and boating activities and take part in group games on two nearby ovals. Accommodation was in huts, not under canvas, and basic camp chores were undertaken by scouts from the Geelong area who dubbed themselves ‘Slushies’. Meals were provided by a professional caterer. It was a week of both outdoor sports and indoor activities with the emphasis on fun. All participants were treated equally including the Governor himself. The camp was a huge success and a second one was held at the same venue the following year, again with Boss Hurst as the Camp Chief. In order to maintain the friendships made during these camps, a reunion was held at the Melbourne Town Hall where it was decided to form the Power House, an organisation for former camp participants, both boys and leaders. The idea had been proposed at the first camp, “a brotherhood under such a name as the Power House . . .to organise reunions and carry on the social service begun in the camp.” [Rear Admiral Napier, from his address at the first camp].

The camps had gained the support of the wider public and it was assumed that they would become an annual event. Lord Somers also saw the possibility of groups bringing children from poorer metropolitan areas to the camp for a holiday by the sea. However the Lord Somers Camp would need its own camp site.

Establishing a permanent location

The hunt began to find an ideal location. It had to meet certain criteria: it must be within a reasonable distance from Melbourne, be close to a creek or river, have a nearby beach and be in a bushland setting. Maps were consulted and likely sites considered. A group, including Lord Somers, set out on a tour of possible sites along Western Port Bay. It was while they were investigating land along the creek in Balnarring East that these trespassers encountered the property owner; rumour has it with a gun tucked under his arm. This was John S. Feehan; the property was Coolart. Feehan invited the party back to his home for afternoon tea over which the Governor explained his ideas. Feehan immediately offered to donate land. Initially it was thought to be an acre in extent, a rough estimate calculated from marked trees but when the land was surveyed it was more than double this. Feehan did not hesitate. The designated land became his contribution. Professional people and people in business and industry donated generously – money, time, equipment, skills – and by the beginning of 1931 the permanent camp was ready to receive its first guests. It was said the boys walked in as the builders walked out.

The buildings of the new camp were rustic in appearance, designed to blend in with its bushland setting but it had resort-like amenities. Nine tile-roofed buildings were arranged around a square to give a feeling of community. There was a common dining room, an assembly hall, open-air theatre and a wireless system. Electric power, warm running water and a sewerage system made it resort-like. It was far removed from camping under canvas.

Early camps

The boys arrived by train from Flinders Street and alighted at the Coolart Road crossing from where they were taken the additional two or three miles to the camp by car. The only compulsory items of ‘uniform’ were a pair of shorts and a scarf, given to each person in the colour of the group into which he was placed. A group leader, who also acted as a mentor, was in charge of each group. The group leaders were men of ‘public repute’ who volunteered their time. Again, Slushies, usually lads who had been to a previous camp, performed the chores. Being selected as a Slushie was regarded as an honour. Each day offered something new. The sports were those played at the original Duke of York camps, team sports in which everyone participated and where ‘having a go’ and working as a team was more important than sporting ability. Fun and high jinks were encouraged. Anyone who broke camp rules was tossed in the creek.

Nicknames were commonplace. Lord Somers became H.E. (His Excellency) while Dr. McAdam, who was now the Camp Chief, was simply Doc. Boss Hurst had stepped aside. His main focus was with the scouting movement and the Geelong area

There was a daily program of games in the morning with an afternoon free to explore the beach or the bush or the lagoon on Mr Feehan’s property, often accompanied by the Camp’s naturalist. The evening was given over to activities such as group singing, films and concerts. Friday night was campfire night. This set the pattern for Big Camp, the main camp in January.

An Easter camp, which H. E. attended, was held in 1931 while a weekend camp, to which over 200 people came, took place in June. This was to farewell H.E. whose term as Governor ended in 1931. Lord Somers and his family went back to England but he promised to return.

He regarded the establishment of the Lord Somers Camp and Power House as one of his greatest achievements during his time as Governor.

Dedication of the Bush Chapel

The 1933 Big Camp was a special one. Lord Somers was in attendance, fulfilling his promise to come back to the Camp. Also the outdoor bush chapel was to be dedicated. At Anglesea there had been a bush chapel for church services ‘under the dome of heaven’s wide arch’ with the forest trees for walls, as one columnist described it. It was a peaceful and inspiring setting. A similar bush chapel was created at Somers on the sand spit that separated the creek from the waters of the bay. In a clearing amongst the foreshore vegetation the camp chaplain, the Rev. P.W. Baldwin fashioned an altar and pulpit from ti-tree. Pews were rustic benches with planks for seats. The cross was made from driftwood. It was described as ‘a beautiful little sanctuary, the silence of which was sacredly disturbed by the music of the waves’. The spit was reached by a bridge, built by the 2nd Field Company of Army Engineers in 1930 to span the creek and access the beach. The dedication was performed by the Camp Chaplain along with the heads of the both the Presbyterian Church and the Methodist Church.

That year the number of boys invited to attend Camp was 100. School boys were nominated by their headmaster, apprentices by their supervisor. It was also noted that 80% of boys who had passed through the Camp had remained members of Power House.

Lord Somers returned to Australia again in 1937, accompanying the Marylebone Cricket team. His excuse for this trip, he stated, was that his Power House tie had worn out and he needed to get a new one. At a reception at the Power House centre in Albert Park he was given a largish wrapped gift. Layer after layer of paper was removed to finally reveal a new Power House tie. His speech reiterated the ideals of the group that had been set up in his name.

The routine for Big Camp followed that of the early camps. In addition there were extra attractions. Prominent people, from the professions, industry, and sport, visited the camp to talk to the young men. A strict time limit of three minutes was imposed for the length of anyone’s speech. When time was up a pistol was fired. Displays were organised, including an air show put on by the R.A.A.F. Planes of various types were landed on the airstrip of a nearby property. Sunday began with a service held by the camp chaplain it the bush chapel while arrangements were made for Roman Catholics to be taken to a church in Crib Point. “Play the Game” remained the fundamental rule.

Repairing the Disruption of the Second World War

All camps were suspended during the war years. The Lord Somers Camp became headquarters for the officers of the RAAF when an Initial Training School for Air Force recruits was built on Coolart land adjacent to and incorporating the Camp.

It wasn’t until 1947 that boys again received an invitation to holiday at Somers. Much had to be done to restore the camp after the permanent military occupation. The small bush chapel was in shambles. Doc wrote “our lovely chapel lay a heap of jumbled ruins in one corner of the sacred site”. Its restoration work was undertaken by Alex Forster who recreated the rustic altar, pews and seats in the shelter of the surrounding trees. It was this open-air chapel that, during the 1950s and 60s in particular, campers from nearby holiday grounds occasionally stumbled upon as they explored the banks of the creek. By then much of the surrounding ti-tree had become festooned with Dolichus vines and, when in blossom, they turned the chapel into a purple and white bower that delighted those who came across it.

The post war years posed a major question for the Camp’s organisers. There was a difference in atmosphere and attitude between the new era and what had prevailed at the earlier camps. Although most people wanted the Camp to continue, some questioned the way in which it was conducted. Was it as relevant? “In economic terms the pre-war pattern of the ‘rich’ public school boy and ‘poor’ boy from industry was reversed, as it was the skilled apprentice who seemed to have more pocket money now.” [Alan Gregory] But despite differences the Big Camp in 1947 followed the same routine and seemed to carry on where the others had left off. One group, in particular, was determined to see the Camp continue. These were the survivors of the 2nd/17th Battalion, a close knit unit who had enlisted from Power House and who had fought in the Middle East, New Guinea (including the Kokoda Track) and later in Borneo and Celebes. They learned, as one soldier wrote, that “what H.E. and Doc had told us was right and true. We believed.” They were firmly resolved to help rebuild the organisation after the war to pass on the principles they had learned at Camp.

The way the camp has evolved

However changes were inevitable. As society, its outlook, and values changed over time the Camp also adapted to keep its relevancy. Closer ties were formed with Legacy in 1963 and girls were given the opportunity to participate when the Lady Somers Camp was set up in 1986. The success of these ventures led to other programs. The Lord Somers’ Camp has adapted its programs and activities over the years in order to reach out to more young people of diverse backgrounds and cultures. However the goals remain the same. They aim to bring out the best in people, to help develop each individual’s potential and to teach people to live together in friendship.

As its numbers swelled, Power House, with its headquarters at Albert Park, became a social hub and home to many sporting teams. Eventually the two groups became separate associations. Today its goals remain founded in earlier principles – to create a stronger more inclusive society through service to others. Its programs still emphasise fun, friendship, care, acceptance and belonging.

Re-locating the Bush Chapel

During the early 1960s the Bush Chapel was facing catastrophe. Erosion was increasingly taking its toll on the sand spit that paralleled the creek. Loss of sand during winter and spring storms was not uncommon but the sand usually returned over the summer months. However, the replacement stopped recurring as sand drift pattern altered. As more and more sand disappeared the chapel was in danger of being undermined and lost, despite the various attempts to stem the erosion. In 1963 it was decided to build a new chapel on the camp side of the creek. The new site was a clearing amongst the trees, located a short way from the main buildings. The layout was traditional with a centre aisle dividing the rows of rustic bench seats facing the stone altar. This new, non-denominational chapel was dedicated in 1963.

Then in 1985 one of the old original buildings had to be replaced. The new structure encroached on the chapel site so a new site was chosen. It was further west towards the property boundary, more remote and nestled in bushland. The third chapel was built here in traditional style with its stone slab altar set before rows of wooden benches. A winding path linked it to the other buildings.

There has been one further major change. The site of this third chapel formed a natural amphitheatre but the Chapel’s E-W orientation and traditional layout did not take advantage of this. It was re-arranged along a N-S line to make the most of this natural feature and today the chapel, now referred to as the Bush Sanctuary, has seating for 250 individuals. Incoming groups initially meet here for the welcome to Camp. It is still one of the Camp’s key structures and serves as a place for quiet reflection as well as the venue for important ceremonies.

Lord Somers’ legacy

Lord Somers died in 1944. Throughout his lifetime he kept his link with both the Boys’ Camp and Power House. He sent gifts and money and any visitor to England who was connected to either association was welcomed to his home in Herefordshire. The ideals behind the Boys Camp he established are still relevant today.

The name Somers is not just synonymous with the Boys’ Camp. The farmland area that had been Balnarring East was subdivided for closer settlement in 1926 and in 1931 the name was changed to Somers to honour this popular Governor.

References:

History of Lord Somers’ Camp and Power House (1929- 1989), Alan Gregory

Information from John Robert, former Deputy Camp Chief, and Michael Pointer

Various contemporary newspaper articles

The Australian Dictionary of Biography

Photographs from the Lord Somers Camp & Power House Archives