By Lance Hodgins

In 1886 the people of Victoria were delivered a Christmas present they didn’t need. A ship had arrived from overseas carrying the deadly smallpox virus amongst its nearly 600 passengers.

Although the Melbourne passengers were quarantined at Point Nepean, everyone was on a knife edge. All the usual security measures were in place, but would that prove to be enough?

The Voyage Out

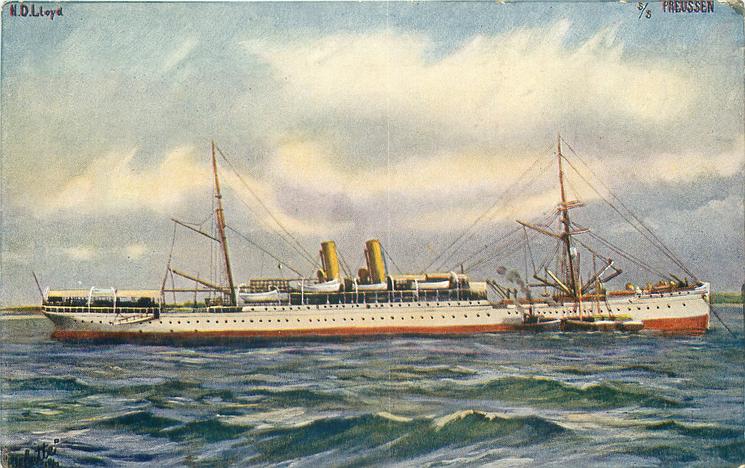

The SS Preussen began its journey from northern Germany, stopping at Antwerp, Belgium, to pick up mostly English passengers who were migrating to Australia. She was a new ship, over 457 feet long, and capable of 14 knots.

After a brief sightseeing stop at Port Said, she passed through the newly-opened Suez Canal and headed for Australian waters.

On reaching Albany’s King George’s Sound, the news was out. One passenger, a 24 year-old Welshman named John Pryce had smallpox. He had gone ashore for a walk around Port Said and apparently contracted the disease there. Within a few days he was feeling very unwell with dysentery. The ship’s doctor eventually recognised the disease as smallpox and immediately sought his isolation and called for mass vaccination on board.

The Preussen was rejected by the West Australia’s health authorities and it passed on to the port of Adelaide. By then Pryce had died and he was buried at sea. Some of the 26 Adelaide passengers were showing signs of smallpox so they were immediately put into the quarantine station on Torrens Island.

On Tuesday December 21 the Preussen left for Melbourne.

The Deadly Smallpox Virus

Smallpox was a feared and highly contagious disease found in all parts of the world. After an incubation period of 1 – 2 weeks, the variola virus began with a rash which developed into blisters which could cover the entire body. It would attack the circulatory system, bone marrow and/or respiratory systems and bring death to one in five people who contracted it.

As early as the 1700s, Dr Edward Jenner had noticed that milk maids were immune to the disease after having had the relatively mild and harmless cowpox. He took cowpox from a milkmaid’s blister and infected a boy with it, then exposed him to smallpox – which he resisted.

This led to the very word “vaccination” – from vacca which is Latin for cow – but the mechanism was not understood as the world was yet to discover bacteria and viruses.

Victoria Braces Itself

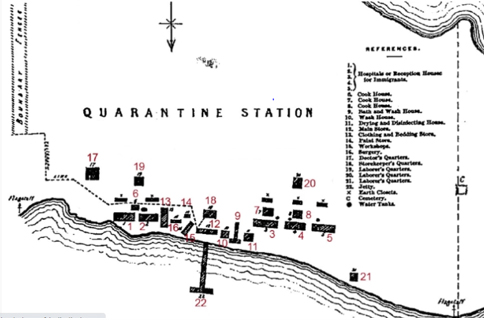

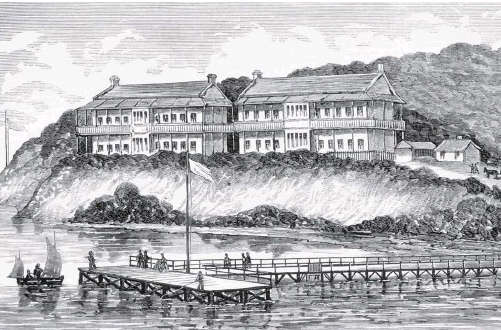

The health authorities were notified of the approaching “smallpox ship” and the quarantine station was hurried into a state of readiness. There would be 250 passengers to quarantine, their luggage to be disinfected, and cargo to be fumigated and forwarded to Melbourne.

The Central Board of Health Officer Dr Sutherland was placed in charge of arrangements and ships and personnel flooded in. The steamer Pharos brought provisions, a provedore and his staff of assistants.

A police force of seventeen constables arrived to patrol the boundary, marked by yellow flags, just as much to prevent the quarantines from leaving as to warn visitors from Portsea who might wander into danger.

Steam tugs arrived with a convoy of lighters – one with 300 tons of coal for the Preussen’s ongoing voyage and several others for the unloading of the considerable amount of cargo.

On the night of Wednesday December 22 the Preussen entered the Heads and anchored at Point Nepean. Dr Sutherland sent his assistant on board and was relieved to learn that there were no new cases of smallpox – as yet – but recognised that this would likely change over the next couple of weeks.

All day Thursday 235 passengers and their belongings were shuttled ashore in lighters.

Most were third class passengers, in crowded steerage where the risk of infection was great. They were predominantly English, with a sprinkling of German, French and Italian. Freshly installed in their buildings, they welcomed the fresh meals as an agreeable change from the fare on the Preussen.

The Vaccine Situation

The next day, Friday December 24, was vaccination day for many of the passengers, stewards and attendants. Dr Sutherland had brought down from Melbourne a good supply of calf lymph for this purpose since the Preussen’s captain had warned him that there had been problems on board.

Many of the crew had been vaccinated but the German medicos had met with considerable resistance from the British passengers who did not trust these “foreigners”. The Captain could not legally enforced vaccination and, as a result, only about one quarter of the passengers had received “the jab”.

Once on English speaking soil, however, nearly everyone agreed and all hoped that it would not be a matter of too little, too late.

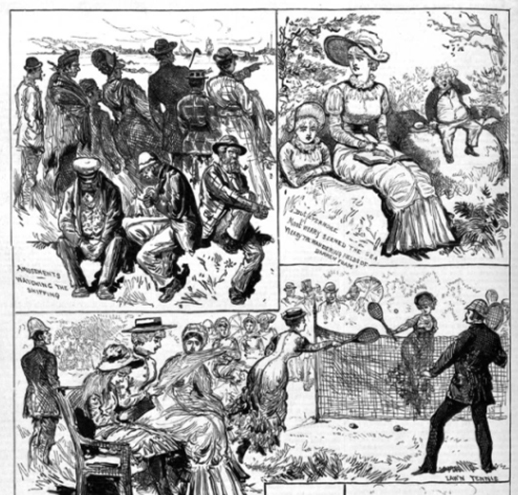

In the meantime there was not much in the way of amusements – a hit of cricket, a throw of quoits, or a stroll along either the back or front beach – so long as you didn’t stray beyond the well-marked boundary, guarded carefully by a dozen constables. They watched as the last cargo was unloaded and the Preussen weighed anchor and started on her voyage to Sydney at 4.30pm on Christmas Eve.

The Melbourne quarantines were looking forward to Christmas Day – they had organised a cricket match to be followed by a concert in the evening.

Christmas Morning December 1886

News broke and spread like wildfire throughout the quarantine station: ONE OF THE CREW OF THE PREUSSEN HAD GONE MISSING.

Panic set in. Some things were certain: he was an assistant engineer on the steamer and a search of the ship could find no trace of him. Van Nyuti, Von Reuter, Von Ryuti, Von Reuti – or whatever his name was – could not be found. His clothes and a lifebelt were also missing.

Security was supposedly strict whilst the various lighters had been alongside the Preussen. Two on the previous afternoon were thoroughly searched, but to no avail.

The Board of Health regarded the escape as a very serious matter and a more detailed description was organised and sent to Police Superintendent Toohey. They were looking for a 24-26 year-old Austrian, 5’8” in height, black eyes, dark complexion and hair, black moustache, slight beard on chin, lightly built and speaking German and Italian. He was last seen wearing a dark tweed suit and a cheesecutter cap. He possibly had a sea-proof suit of waterproof clothing with him.

Days Go By…

By the time the Preussen arrived in Sydney there were with several confirmed cases of smallpox – many of them amongst the crew. They were taken to the isolated hospital hulk Faraway. Adelaide was also reporting several new cases.

By the end of the Christmas weekend the cases at Point Nepean were multiplying and the authorities began to regard Von Nyuti’s escape as increasingly serious. Although he had not shown any signs of smallpox by those who last saw him on board, he was potentially a huge danger to the health of thousands – particularly if he reached the streets of Melbourne.

A reward of £20 was announced and the sightings poured in.

One promising report occurred several days after Christmas. A tourist from Melbourne was on the Sorrento back beach when he was approached by a man dressed in dungaree trousers over another pair, looking as if he had just come out of the ocean. He asked for a drink of water and offered a shilling if he would get him a tinful. When asked who he was, the man had stated that he was an engineer on the Preussen at the quarantine station. He then sought directions to the jetty and took off in that direction.

Later that same day a young friend of the Melbourne visitor reported the same man on board the Ozone excursion steamer on its way back to Port Melbourne. When he tried to speak to him he was told to mind his own business and on docking he had taken a train into the City. He was now wearing a light tweed suit and hard black hat, but when a description of the fugitive was published in the Police Gazette, the young man realised who he had seen.

A man answering Von Nyuti’s description was seen in company at the Half Way Hotel on the Ferntree Gully Road at Mulgrave. He was a “sailor-looking man” who did not seem to be seeking work but was travelling to the Dandenongs.

One strong lead had him on the way to Sydney and the police chiefs in Albury received bulletins to be on the lookout.

Into The New Year

The combined Australian smallpox numbers swelled to over 100, and it became the most serious invasion of the disease into the colonies for a long time. The fact that those affected were in quarantine was some solace but the escape of Von Nyuti made people feel uneasy.

Was he now carrying the seeds of the hated disease throughout the streets of Melbourne? How could he have escaped the security of the quarantine station? How had he changed his appearance?

Back at the quarantine station, one of the passengers suggested that the fugitive’s clothes had been taken ashore by another passenger who had been friendly with Von Nyuti. On interrogation, the friendship was admitted to but the passenger denied helping him and claimed that he had not had anything to do with Von Nyuti for the last few weeks of the voyage.

The authorities, and particularly the Captain of the Preussen, were keen to defend their own security measures. Von Nyuti was allegedly too intoxicated (as observed by some of the crew) to take his normal shift in the engine room. The lighters and the steamer had been thoroughly searched. A tidal expert observed that there was no hope of swimming ashore from the Preussen as it had been anchored in mid-channel where the tides run fast and strong. Von Nyuti must have fallen overboard and been taken by sharks – or simply drowned as he was carried out the Heads. The missing life belt lent credence to the theory that he had tried to swim ashore.

Yet the sightings continued to pour in.

He was seen herding pigs at Braybrook – a doubtful pastime for a fugitive but one which nevertheless had to be checked out. A senior detective investigated and found that the swineherd was none other than a Frenchman going about his normal farming activities.

A young man reported to the Central Board of Health that whilst shooting at Campbellfield near Coburg he noticed a man answering Von Nyuti’s description. He was dressed in a dirty pair of trousers and singlet and sunburnt so much that he apparently had been exposed to the elements for some time. More suspiciously, he seemed to be rubbing his skin as if he was terribly itchy. The local police investigated and subsequently found that their man was an Irishman well known to them and already on their books as a case of insanity.

Well into January and a tip-off led police to a house near the Melbourne docks. They converged on the house in Yarraville only to find that a French fisherman was living there.

A few days later a man was arrested at Wagga Wagga and the Preussen’s officers were sent up to New South Wales to identify him. False alarm.

Von Nyuti is working in Gippsland! Police rushed to a farm at Jumbunna, near Poowong, but it was another blank.

At about the same time, the case of the wet man discovered on Sorrento’s back beach, and later seen on the Ozone, was put to rest. The actual person had been found and he was NOT Von Nyuti.

The Final Chapter

Finally, in late February and almost two months after the disappearance, there was much excitement in Port Philip Bay.

A Geelong fisherman, named Johnstone, landed on Mud Island with his seine nets and was immediately confronted by a stranger in a semi-nude state who was gesticulating wildly and behaving in a most eccentric manner. When Johnstone hailed him, he yelled something back in broken English, then abruptly turned and ran away.

After dealing with their nets, Johnstone and his companions looked for the man but failed to find anyone, so they left and returned to Queenscliff. It was only in later conversation with their fellow fishermen that the topic came up of “that German chap with smallpox” and they felt they should report the incident.

They called the Sorrento Police but received no immediate response. Had they believed that it was too far for anyone to swim? Were the tides too strong? The local police had, in fact, begun a thorough investigation. They knew that Mud Island offered a supply of rabbits and shellfish and a man could easily exist on the uninhabited island for some time. There were also several sheds there erected by some fishermen for their occasional shelter from the weather.

Finally, it was reported that Sorrento police had traced the mystery man.

Apparently two seine-net fishing boats had come into contact when they arrived at the same time on the mud flats around the island. One of the men, a Norwegian, had walked into the other party’s nets with a rope of his own net and caused an altercation. Being surprised, he had answered in his own language and then hastily cleared out, so that when Johnstone and his party went to look for him he was not be found, having hastily left on his boat.

The trail was cold and nothing more was heard of Von Nyuti – real or imagined.

When the last passengers of the Preussen were released from quarantine in March 1887, 14 people had died.

Post scripts

A subsequent report by the Victorian Central Board of Health reflected poorly on the Preussen and it owners. Conditions on board were evidently quite unhygienic, precautions against smallpox were ludicrous, and protection from the infected body of John Pryce was lacking. It was rumoured that, early in the voyage, another passenger had been hastily buried at sea.

The mostly British passengers were loaded at Antwerp presumably to avoid meeting stricter English regulations. Travelling on a cut rate fare, these steerage passengers knew they would in for a rough time of it but few of them anticipated the events which would follow.

As a result of the varying approaches to meeting the danger – in particular the non-acceptance of the vessel by WA – one of the first powers handed to the new Commonwealth of Australia in 1901 was a national and uniform quarantine system. Many felt that if the Preussen had been intercepted and quarantined in Perth then many of the further problems would have been avoided.

Today, smallpox is the only human disease to be totally wiped out by vaccination. As a result of a decade-long blitz, the World Health Organization was able to announce in 1980 that, instead of causing two million deaths a year, it had been eradicated.