JOHN Basilone was born in Buffalo, New York State, on 4 November 1916. Completing middle school at the age of 15, he dropped out prior to attending high school.

After working for a short time as a golf caddy at the local country club, Basilone enlisted in the army and completed his three year enlistment with service in the Philippines, where he was a champion boxer.

Back home he worked as a truck driver, but after a few months he wanted to go back to Manila. He believed he could get there faster as a marine than in the army. He enlisted in July 1940 and, after his initial training, was sent to Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands as a member of the 1st Marine Division.

While on Guadalcanal his fellow marines gave him the nickname “Manila John” due to his prior service in the Philippines.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, the US and her Pacific allies Australia and New Zealand wanted to kick the Japanese off Guadalcanal to stop the threat to South Pacific supply lines. It was to be the first major Allied offensive against the Empire of Japan, which had been slowly spreading out across the eastern hemisphere like the red and white starburst on its war banner.

The US-led forces landed on Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942, surprising the Japanese and seizing an airstrip called Henderson Field. But the Japanese clung on tenaciously and fought bloody battles against the Allies before finally relinquishing the island in February 1943.

It was in one of those fierce counter-attacks on 24 October that John Basilone stepped up to the mark. A regiment of 3000 Japanese soldiers from the so-called “Courageous” Sendai Division defending the airport descended on John’s unit.

The Japanese forces began a frontal attack using machine guns, grenades and mortars against the American heavy machine guns.

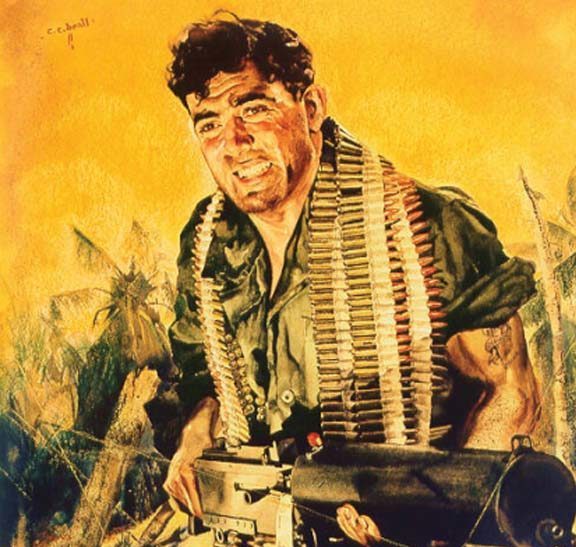

Basilone led the defence with two machine gun sections of about 15 men. They fought almost without a break for the next two days.

Basilone’s comrades were cut down around him until he was left with only two other marines fighting off wave after wave of enemy troops. He repaired a machine gun, helped move another one into position and maintained continual fire until backup arrived.

Basilone took enemy fire while running through the jungle to pick up more machine gun belts to keep his comrades supplied. By the time the next dawn broke he was fighting with just a machete and a .45 pistol. The Japanese regiment was laid to waste. About 3000 Japanese Banzai soldiers had been killed in the attack and the airfield had been successfully defended.

America had itself a new hero.

For his actions during the battle, Basilone would receive the United States military’s highest award for bravery, the Congressional Medal of Honor, signed by President Franklin D Roosevelt.

After Guadalcanal the 1st Marine Division came to Australia to “rest and refit.”

Up to 30,000 men were accommodated at Balcombe near Mt Martha.

Balcombe Army Camp

THE first huts were erected at the Balcombe Army Camp in 1939 and although it was used by the Australian army, including the 39th Battalion prior to its departure for New Guinea and the Kokoda Track, it was used extensively by American forces for most of the war years.

After the war it was the home of the Australian Signals and Survey Corps until it moved to Watsonia in 1970. The Army Apprentices School was at Balcombe between 1948 and 1982 where plumbers, electricians, fitters and turners, mechanics, carpenters and other trades were trained. The last building left Balcombe in August 1999 and the area is now an upmarket subdivision, a private school, an oval and a park. The latter features a boardwalk from the mouth of Balcombe Creek to the oval.

Some of their rest was spent practising beach landings from HMAS Manoora near cliffs at Dromana and McCrae. On 22 February the division participated in a parade past Melbourne Town Hall. More importantly, in a ceremony at Balcombe barracks on 21 May 1943, the division received a Presidential Citation for its epic battle at Guadalcanal. Two of its veterans, John Basilone and Mitchell Paige, were presented with the Congressional Medal of Honor.

After receiving his medal, Basilone returned to the US to participate in a war bond tour.

Following a massive homecoming parade on 19 September 1943, he toured the country raising money for the war effort and achieved celebrity status.

Basilone became the living embodiment of bravery and the American fighting spirit. There were parades and parties in his name. From movie stars to city mayors, everybody wanted to meet the marine who had shown the Japanese could be broken.

But Basilone preferred standing behind a machine gun to posing in front of the cameras. He felt out of place and requested a return to the operating forces fighting the war. After a number of his requests were refused, the Marine Corps eventually relented, but before he left for war again, Basilone was to find love.

While he was posted at Camp Pendleton, where he trained marines for coming Pacific battles, he met Lena Riggi. She was also a marine sergeant (a reservist) who had one less stripe than John.

The two fell in love and Basilone realised he would likely have to leave Pendleton towards the summer of 1944. It wasn’t easy to balance their different schedules, yet he was determined to marry Lena before he returned to the Pacific.

“I wanted to know how it was to love somebody the way Pop loved Mama,” he said. “At least I wanted a few days, or weeks if I could get it, to know what it was like to be married. I wanted to be able to say ‘I love you’ a few times and mean it. Lena agreed to marry me. We set the date for July 10th, 1944.” As expected, Basilone shipped out one month after their wedding.

On his return to combat, Basilone was assigned to the 5th Marine Division, which was about to undertake the invasion of Iwo Jima.

On 19 February 1945 he was serving as a machine gun section leader in action against Japanese forces on Red Beach 11.

During the battle, the Japanese concentrated their fire at the incoming Americans from heavily fortified blockhouses staged throughout the island. With his unit pinned down, Basilone made his way around the side of the Japanese positions until he was directly on top of a blockhouse.

He then attacked with grenades and single-handedly destroyed the entire strong point and its defending garrison.

He went on to fight his way toward the airfield and aided an American tank that was trapped in an enemy minefield under intense mortar and artillery barrages.

He guided the heavy vehicle over the hazardous terrain to safety despite heavy fire from the Japanese.

As he moved along the edge of the airfield he was killed by Japanese mortar shrapnel.

His actions helped marines penetrate the Japanese defence and get off the landing beach during the critical early stages of the invasion.

For his valour during the battle of Iwo Jima, John Basilone was posthumously approved for the Marine Corps’ second highest decoration for bravery, the Navy Cross, and became the most highly decorated marine to be killed at Iwo Jima. He was the only enlisted marine to receive the Purple Heart, Congressional Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross.

He was later interred in Arlington Cemetery in Virginia.

It was on her 32nd birthday that Lena learned her husband had been killed in action when she received a telegram:

“Deeply regret to inform you that your husband, Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone, USMC, was killed in action February 19, 1945 at Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, in the performance of his duty and service to his country. When information is received regarding burial, you will be notified. Please accept my heartfelt sympathy.”

The telegram was sent in the name of General Alexander Vandegrift, who had been Basilone’s commanding officer at Guadalcanal. It was he who had presented Basilone with his Medal of Honor at Balcombe.

Because Lena was Basilone’s closest family member, she received the $10,000 life insurance payout given to the families of all American serviceman who had died as a result of war injuries. She promptly gave it to the Basilone family.

Lena never remarried. She survived her husband by 54 years. When she died in 1999, Lena was still wearing the wedding ring her beloved “Johnny” had given her. Her grave is at Riverside National Cemetery in Riverside, California. She had declined the government’s offer of a burial spot near her husband at Arlington.

How Basilone won the Medal of Honor

THE President of the United States in the name of the Congress takes pride in presenting the Medal of Honor to Sergeant John Basilone, United States Marine Corps, for service as set forth in the following citation:

“For extraordinary heroism and conspicuous gallantry in action against enemy Japanese forces, above and beyond the call of duty, while serving with the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division in the Lunga Area, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, on 24 and 25 October 1942.

While the enemy was hammering at the marines’ defensive positions, Sergeant Basilone, in charge of two sections of heavy machine guns, fought valiantly to check the savage and determined assault.

In a fierce frontal attack with the Japanese blasting his guns with grenades and mortar fire, one of Sergeant Basilone’s sections, with its gun crews, was put out of action, leaving only two men able to carry on. Moving an extra gun into position, he placed it in action, then, under continual fire, repaired another and personally manned it, gallantly holding his line until replacements arrived.

A little later, with ammunition critically low and the supply lines cut off, Sergeant Basilone, at great risk of his life and in the face of continued enemy attack, battled his way through hostile lines with urgently needed shells for his gunners, thereby contributing in large measure to the virtual annihilation of a Japanese regiment.

His great personal valour and courageous initiative were in keeping with the highest traditions of the US Naval Service.”

How Basilone won the Navy Cross

THE President of the United States takes pride in presenting the Navy Cross posthumously to Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone, United States Marine Corps, for service as set forth in the following citation:

“For extraordinary heroism while serving as a Leader of a Machine-Gun Section, Company C, 1st Battalion, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Iwo Jima in the Volcano Islands, 19 February 1945.

Shrewdly gauging the tactical situation shortly after landing when his company’s advance was held up by the concentrated fire of a heavily fortified Japanese blockhouse, Gunnery Sergeant Basilone boldly defied the smashing bombardment of heavy calibre fire to work his way around the flank and up to a position directly on top of the blockhouse and then, attacking with grenades and demolitions, single-handedly destroyed the entire hostile strong point and its defending garrison.

Consistently daring and aggressive as he fought his way over the battle-torn beach and up the sloping, gun-studded terraces toward Airfield Number 1, he repeatedly exposed himself to the blasting fury of exploding shells and later in the day coolly proceeded to the aid of a friendly tank which had been trapped in an enemy mine field under intense mortar and artillery barrages, skilfully guiding the heavy vehicle over the hazardous terrain to safety, despite the overwhelming volume of hostile fire.

In the forefront of the assault at all times, he pushed forward with dauntless courage and iron determination until, moving upon the edge of the airfield, he fell, instantly killed by a bursting mortar shell.

Stouthearted and indomitable, Gunnery Sergeant Basilone, by his intrepid initiative, outstanding skill, and valiant spirit of self-sacrifice in the face of the fanatic opposition, contributed materially to the advance of his company during the early critical period of the assault, and his unwavering devotion to duty throughout the bitter conflict was an inspiration to his comrades and reflects the highest credit upon Gunnery Sergeant Basilone and the United States Naval Service.

He gallantly gave his life in the service of his country.

For the President, James Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy.”