By Ilma Hackett – Balnarring and District Historical Society

Balcombe: the Mornington-Mt Martha district is dotted with this name. There is a Balcombe Street, Balcombe Drive, Balcombe Reserve and the Balcombe Creek. It’s the name of a college and a pre-school and was the name of an army camp. Who or what was Balcombe? A clue may be found in St Peters Anglican Church where a stained glass window commemorates the pioneering Balcombe family, while a drinking fountain, recently re-located to ‘Mornington Park’, has a plaque to Alexander Balcombe “early pioneer and benefactor” whose leasehold station ‘Tichingorourke’ once covered the area that is now Mornington.

‘Tichingorourke’ / ‘Checkingurk’ – “The Voice of the Frogs”

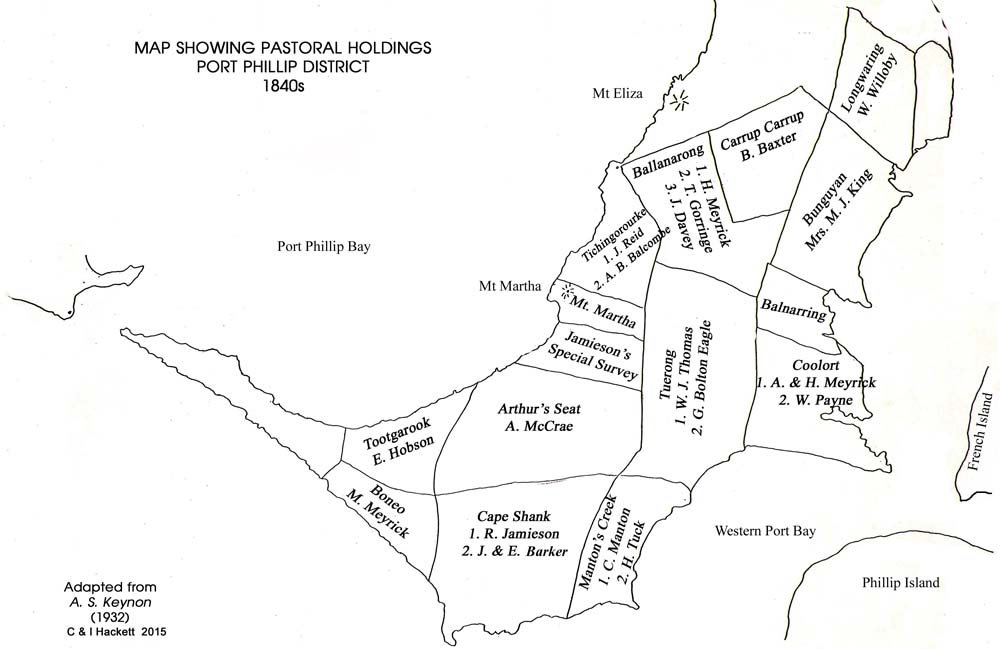

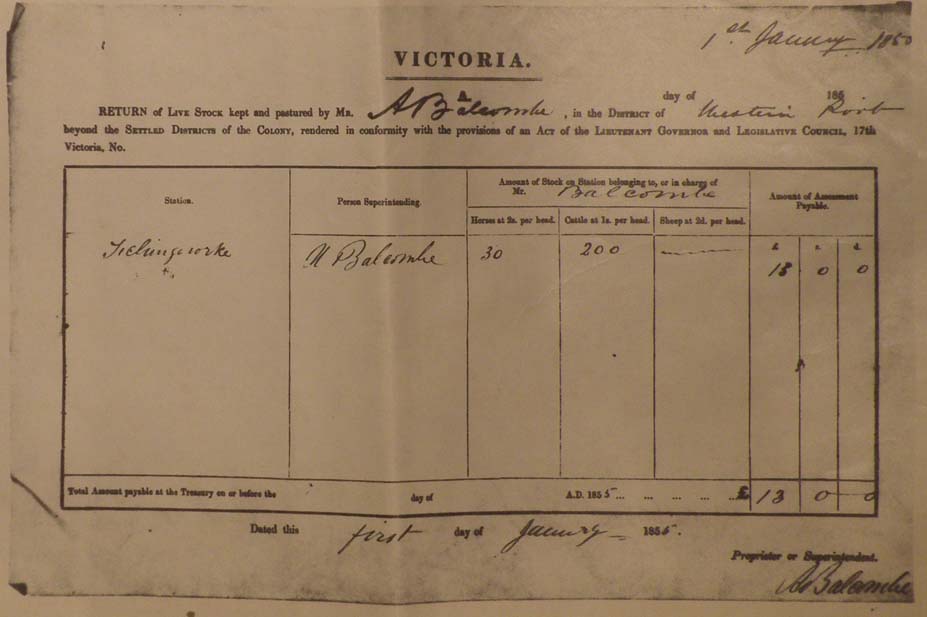

Crown land of the Port Phillip District was opened up to squatters in the late 1830s – early 1840s. Land could be taken up under licence or lease for pastoral pursuits. An annual fee of £10 was imposed with an additional cost per head on the number of stock held on the run – initially one half-penny per sheep, three half-pence for cattle and three pence for horses. [Billis & Kenyon: Pastoral Pioneers of Port Phillip, preface p vi]

Six thousand acres of land, covering the area from Tanti(ne) Creek in the north to a knoll at the base of Mt Martha in the south and from the coast inland as far as the present Moorooduc Highway, was once the grazing run ‘Tichingorourke’. The name was Aboriginal, echoing the sound of frogs heard along the creek that wound across the land. Smythe’s survey map of 1841 described the land as open forest country, good grass, timbered with gum, she-oak, stringy bark, lightwood and wattle trees.

The run was first taken up by Captain James Reid who established his station near the junction of two creeks a few miles inland from the estuary. He ran cattle. At first things prospered for the early squatters but the years between 1842 and 1844 saw supply far outstrip demand; cattle were selling at a fraction of their original price and sheep were being used for tallow. Banks failed and, in an economy based on credit and loans, those who had not set aside cash had nothing to fall back on. Reid went bankrupt and, having paid his creditors ten shillings in the pound, returned to England with his young family. [Hales & Le Cheminant: The Letters of Henry Howard Meyrick letter XXVIII ,1847 p.43]

The lease was taken up again in 1846 by A.B. Balcombe: “Grandfather and his bride came to a weatherboard hut near a level crossing of gravel over a creek” [Dame Mabel Brookes Crowded Galleries, p.2]

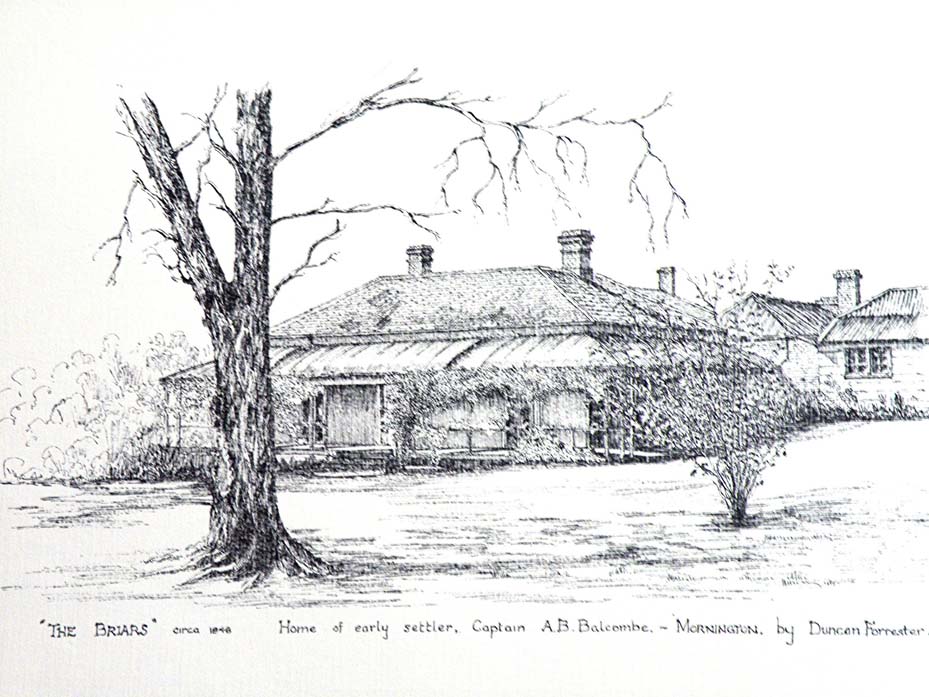

“Grandfather” was Alexander Beatson Balcombe and his “bride”, Emma Balcombe née Reid. The couple had been married for five years and had a two-year-old daughter, Jane. The weatherboard hut was a slab construction with a thatched roof erected by Captain Reid (no relation to Emma). Although somewhat rough-hewn, the hut or cottage was quite comfortable and was described by Richard Howitt when he walked the length of the Peninsula in 1843 as being “outwardly very rustic yet agreeable . .one of the rooms I entered was a strange medley of military – elegant English – and homely bush furniture. Yet everywhere was evidence of taste…”. Neighbour, Georgiana McCrae made a sketch of the station in 1844 which shows not only the homestead cottage but numerous outbuildings, fenced paddocks and cleared land with shady trees.

The dusty road that linked the outlying stations of the peninsula to the increasingly sophisticated centre that was Melbourne crossed a creek at a ford not far from the homestead cottage.

A turbulent boyhood

Alexander Balcombe was born in 1811 on the South Atlantic island of St Helena, the sixth child of William and Jane Balcombe. His father was a respected trader and representative of the British East India Company. The little boy had a privileged childhood until the family’s abrupt departure from the island when he was seven years old. Napoleon Bonaparte had been exiled to the island in 1815 and the family’s friendship with the former French emperor had aroused the suspicions of British authorities. William sailed for England to clear his name. They never returned. Instead, in 1823, William Balcombe was offered the posting of Colonial Treasurer in the fledgling colony of N.S.W.

When the Hibernia docked in Sydney Cove the following year, the passenger list included W. Balcombe Esq., Mrs Balcombe & family and 2 domestics, Mrs Abel and child. It had not been a happy voyage. Eldest daughter, Jane had died while the ship was crossing the Indian Ocean and had been buried at sea. Mrs Abel was second daughter, Betsy, whose husband had abandoned her, leaving her to raise an infant daughter. “Family” were the three sons- William Jnr, Thomas and Alexander. The young Alexander was thirteen years old.

The family settled into their new home in O’Connell Street in the centre of Sydney. It was a pleasant, two-storey, brick house and the family was welcomed into Sydney society. Along with his brother Thomas, Alexander attended Sydney Grammar School. Things changed with the death of his father six years later. The family was left with little money, mounting debts, and no house to live in as the O’Connell Street property had been leased. Their assets were sold, including land grants near Goulburn but they retained land at Molonglo where William Junior was farming. On completing school Alexander was given employment as a clerk but was dismissed for negligence. In the turmoil that followed his father’s death, the teenage Alexander left Sydney to join his brother at Molonglo to take up life on the land. His mother, sister Betsy and her child were to return to England.

In 1839 Alexander, now in his 20s, joined a party led by a neighbour, William Rutledge, trekking south to explore the Port Phillip District of the colony. The area had recently been opened up by the government for grazing. Impressed by the land’s potential he returned to the Goulburn district and made preparations to move south as a permanent settler.

Marriage

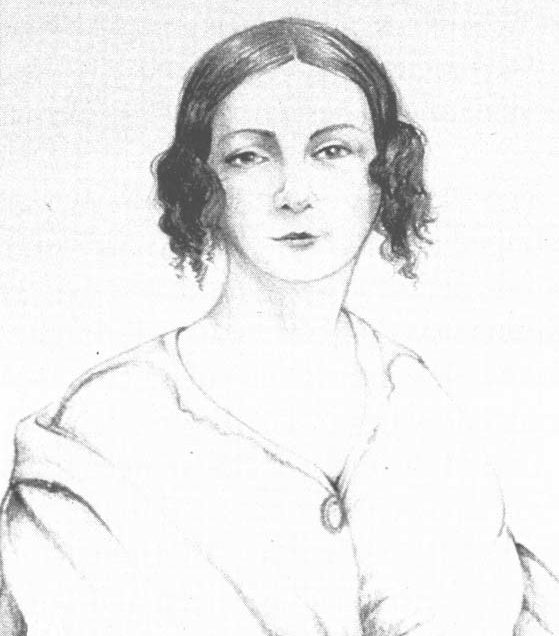

Part of his plan was to find a wife and he courted Emma Juana, younger daughter of his neighbour, retired naval doctor, David Reid of ‘Inverary Park’. Tall and blue-eyed, she was a practical and even-tempered young woman whose voice held a faint Scottish lilt. Their wedding took place in 1841, close to Emma’s eighteenth birthday. Alexander was thirty.

Within a few months preparations were complete. Leaving his new wife, now pregnant, at ‘Inverary Park’ with her family, Alexander overlanded cattle south to a lot on the Merri Merri Creek, a temporary arrangement until he could acquire his own run. Once set up there he returned to Goulbourn and in

September, 1842 brought Emma and their baby son back to Melbourne by ship. The little boy, Stephen, grew to be a happy toddler in their new home but, sadly, died accidentally when he was eighteen months old; according to family folklore he had eaten green apples. Emma was heartbroken and, when she again found herself pregnant, went back to ‘Inverary Park’ to await the birth of her new baby. A daughter, Jane Emma was born at the close of 1844.

Neighbours to the McCrae family

By March 1846 Alexander had acquired the lease to Tichingorourke and the family moved to the peninsula. Over the next few years he set about stocking his new run, extending the yards Reid had already constructed, taking on staff and planning for the future. One of the first things he did was to choose a new location for his house. A prefabricated weatherboard building was purchased and brought from Melbourne. This was sited on the hill to the south of Reid’s cottage. It consisted of two rooms and a small scullery. .The building was roofed with wooden shingles, cut and shaped on site. This dwelling, ‘The Hutch’, provided living space while a permanent homestead was being built. A son, Alexander Stephen (Alick) was born in 1847 and on the birth certificate his father gives his status as ‘settler’.

The land, Alexander decided, “was bad for sheep, fair for cattle, good horse country and in 1854 he was grazing 50 horses and 250 cattle”. [Dame Mabel Brookes: Crowded Galleries, p 6]

Emma made the acquaintance of her nearest neighbour, Georgiana McCrae. The McCraes had the Arthur’s Seat run, twelve miles to the south. The two women shared a Scottish background but whereas the aristocratic Georgiana clung to her European heritage, Emma was a ‘colonial’ having been born at sea a few weeks before the ship bringing the Reid family to Australia had docked. She had never known a life in Europe and had been brought up in rural NSW. Georgiana, who had come to live on the peninsula the previous year, gave Emma flower cuttings – wisteria and roses, a camellia and olive trees. These flourished and can still be seen in the gardens surrounding the homestead.

In the early 1850s Peninsula lands were being surveyed for sale as selections. Alexander applied to buy his land under Pre-emptive Right. He was granted the square mile around his homestead but certain areas of his original 6,000 acre lease were reserved for specific purposes. This included land along the coast and an area for a proposed township. Alexander gradually bought up further acreage until he owned outright about 1,100 acres. He also purchased several lots in the new township of Schnapper Point, just a few miles from his home. Now that tenure was secure he set about enlarging and improving his buildings.

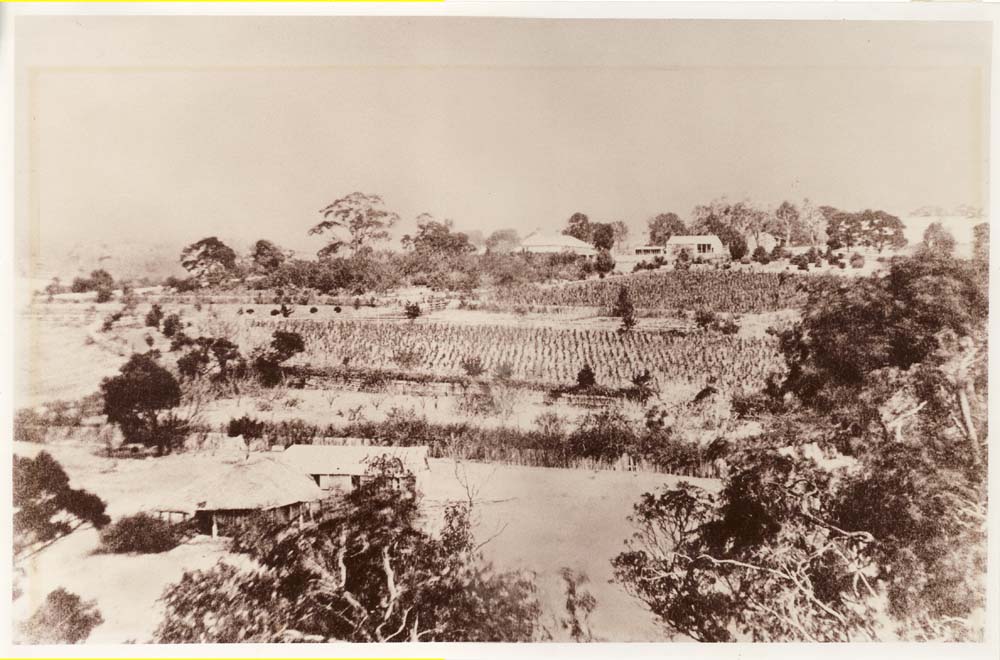

A brick homestead was joined to ‘The Hutch’. It had two main rooms, and two small rooms at either end of a veranda. Bricks for the building were made from clay by the creek and fired nearby in a small kiln. Balcombe employed Thomas Coxhell, a ‘brick master’ from England to oversee the work. It was roofed in slate. According to Balcombe descendant and family historian, Dame Mabel Brookes, ticket-of-leave men carried out the construction which continued over the next decade. A kitchen building of four rooms was separate but linked to the homestead by a covered walkway. A wing, consisting of laundry, dairy and extra room of corrugated iron, was sited further up the hill. Outbuildings, including a barn and stables were added to the farm over a period of time

In the meantime the family was growing. In 1850 Emma gave birth to a third son, William but again heartbreak; the child died within weeks of birth. A daughter, Agnes, joined the family in 1851. Emma and Alexander now had three lively youngsters. . An additional bedroom wing of timber was then added to the homestead. This had four rooms and a veranda overlooking the orchards and the valley to the north.

Gold fever

Everything that was happening in the early 1850s was overshadowed by one momentous event – the discovery of gold. People flooded into the newly-proclaimed state of Victoria. Between the years 1852 and 1854, two hundred and fifty people per day arrived in Melbourne [A.G.L. Shaw ‘La Trobe’s Melbourne’. Victorian Historical Journal, Sept. 2002, p 41]. All were intent on finding their fortune at one of the diggings that sprang up throughout Victoria. Alexander himself was lured to the goldfields, probably to Bendigo to join his brother-in-law. While he was away Emma was left to oversee the station hands and the household staff. It was during Alexander’s absence that two armed bushrangers, having escaped from Van Diemen’s Land and landing in an isolated bay on the west side of the peninsula, ransacked the homestead. Emma fed the men, gave them provisions and directed them to the Melbourne Road. The women and children at the homestead were left terrified but unharmed.

Alexander’s prospecting did not yield much gold and he realised there was more to be made producing food for Victoria’s rapidly increasing population. He returned to ‘Tichingorourke’. Droving cattle to Melbourne took several days and in 1853 Alexander purchased land, at about the midway point, to be a resting place for his livestock. The area is now Mentone and the road that was originally the track to his land became Balcombe Road. He also bought land in East Melbourne where a pre-fabricated cottage was erected. This was later replaced by a more substantial home –‘Eastcourt’ – the Balcombes’ city home.

Briars House – an echo of St Helena

Throughout the late 1850s and 1860s Balcombe’s wealth continued to increase. As the township of Schnapper Point grew so did his prestige. He became a member of the first Mt Eliza District Road Board, a fore-runner of the Shire council. He was the first trustee and warden of St Peter’s Anglican Church. He promoted the building of a school and was appointed a J.P. for the district. His notebook from the time mentions some of the cases that came before him: “salvaging a body from the sea; finding a child dead from climbing a tree for possums; re-making the broken end of the Mornington pier” [Dame Mabel Brookes: Memoirs, p 18]. Two more daughters had been born, Maria in 1855, then Lucia three years later. By then the Balcombe property had a new name – Briars House, named both for the home where he had grown up on St Helena and the home he had known in N.S.W. Eldest son Alick, twelve years old, was enrolled at the Melbourne Church of England Grammar School where he would be a boarder for the next couple of years.

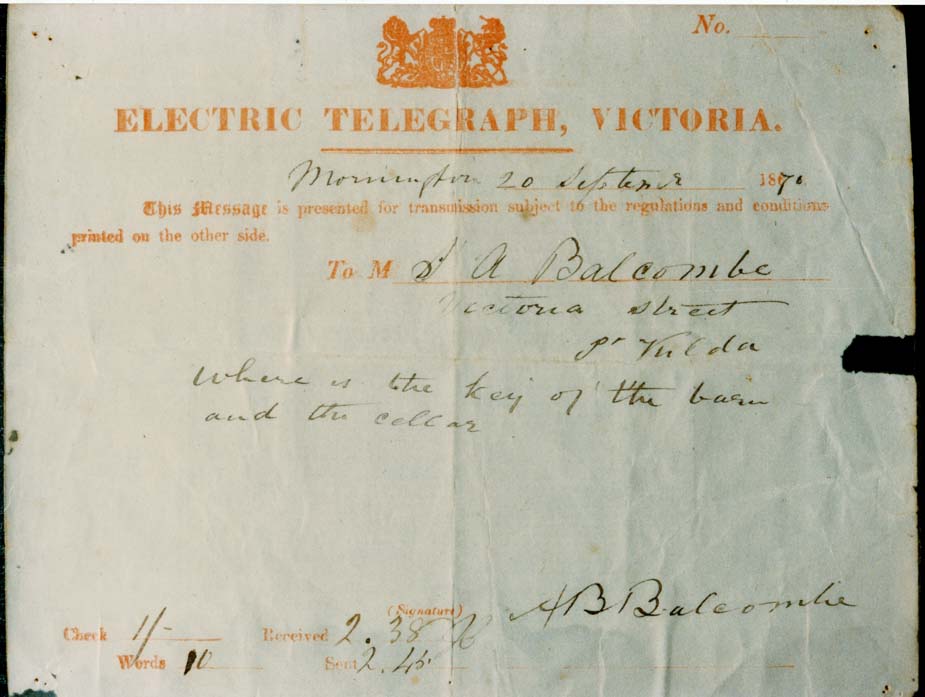

Now wealthy, Alexander and Emma designed a grander main wing for their farmhouse. This incorporated a front entrance accessed from a circular drive at the head of the long, tree-lined avenue to the property. The new wing had four spacious rooms, each with its own marble fireplace. A central hallway linked it to the rest of the house. French windows opened from each room onto a covered veranda that ran around the building. Beneath one of the rooms was a large cellar where things needing coolness could be kept, including the wine that was produced from the vineyards Balcombe had planted. This venture wasn’t a great success and the family called the wine “Balcombe’s Vinegar”. Wine-making was not a pursuit Alexander kept up. The remaining vines were eventually grubbed out in the 1920s after outbreaks of phylloxera.

Another son was born to William and Emma in 1861 – Herbert Henty (or ‘Bertie’).

Emma fell ill in 1864 and went to Melbourne to be cared for by friends. During her absence daughter Jane became the lady of the house, looking after the smaller children and supervising the household. Alexander wrote poignant letters to his wife, telling her of life on the farm and how much she was missed. She returned to Mt Martha and the couple’s last child, daughter Alice was born in 1865. This completed their family of two living sons and five daughters.

Family and Financial Difficulties

The late 1860s ushered in a period of family and financial difficulties. The property was in arrears. Friction had developed between husband and wife. ‘Eastcourt’ became Emma’s preferred home and her absences caused problems; on one small practical matter an urgent telegram was despatched asking where the cellar and barn keys were kept. Although she returned to The Briars, Emma increasingly yearned to be at ‘Eastcourt’. She found their Mt Martha property too isolated and fretted about her children’s social prospects. She urged Alexander to lease out the property and move the family to East Melbourne. He wanted to stay; he was happiest on the land. Deeply unhappy, Emma considered leaving Alexander. This drew a letter of reproval and advice from her older sister: Lady Murphy pointed out that country living was less expensive and healthier and that by remaining at The Briars they could afford to give Alick and Jane a good start in life and the younger children a good education. She reminded Emma of her wifely duties and urged her to stay with her husband despite his “difficult nature”. Then father and eldest son had a heated quarrel that resulted in Alick leaving home and going to Queensland to work on an uncle’s property. An embittered Alexander disinherited him.

They were deeply in debt. Alexander considered leasing all or part of the property. He mortgaged it for £3,000 in 1871 and that took five years to repay. Finally, in 1873, the homestead and approximately 900 acres were leased to T. Baines and A. Cane and the family moved to East Melbourne.

Alexander’s health had deteriorated. Even so he continued to take an interest in his country property and kept up a long-standing dispute with the Shire over the building of a road through his land. He died from pleuro-pneumonia at ‘Eastcourt’ in 1877 at the age of 66 years.

“The Briars” was left to Emma for her lifetime. For a brief period, after Alexander’s death, the property was with Henry (“Money”) Miller and his son. Miller was a prominent banker, insurance agent, money lender and politician and this may have been a form of financial assistance to Emma. However by 1881 Emma had regained the property which remained with Balcombe descendants for almost another century.

A new generation – a new purpose

Emma did not return to live at ‘The Briars’. In 1891 the Balcombe’s youngest daughter Alice and her husband, Melbourne solicitor Harry Emmerton, ‘leased’ the farm from Emma at one shilling per annum. The Emmertons used the homestead as a holiday residence while Harry managed the business-side of the farm for his mother-in-law. “He fattened cattle for grandmother, grew some crops, had riding horses and the family reaped the advantages of vegetables and flowers sent to Melbourne every week” [Dame Mabel Brookes: Memoirs p.17]. Alterations were made to the main building to suit the Emmertons’ life style. The bedroom wing was demolished and in its place a ballroom was built. It was constructed of red, factory-made bricks with full length French windows opening onto the garden. A magnificent fireplace, modelled on one in a stately home in England, occupied almost an entire wall while the raised ceiling added to the feeling of spaciousness. The house rang with music and laugher. The Emmertons had a croquet lawn and a tennis court built for the entertainment of their guests. Their only daughter, Mabel, invited her friends to spend weekends at ‘The Briars’. Amongst them was her beau, a Davis Cup player with the Australian team. Norman Brookes proposed to Mabel during one such weekend. Mabel, later Dame Mabel Brookes, gives a picture of life at The Briars during those years in several books she wrote. She also drew on the experiences of her grandmother to describe colonial life.

In her later years, Emma reluctantly re-visited her old home. She had suffered several small strokes that curtailed her movements. When there she loved to sit on the wide veranda shaded with the climbing roses and wisteria she had planted in earlier days and reminisce. Her favourite rose, a climber named Cloth of Gold, rambled over a wooden trellis in the garden Emma died in 1907 and was buried alongside her husband, infant sons and two of her daughters in the Old Melbourne Cemetery.

Alexander & Emma were the first of six generations of the same family to call ‘The Briars’ home.

The Briars Today

Two gate posts either side of a cattle grid mark the entrance to The Briars. Today it is public parkland managed by the Mornington Peninsula Shire Council. The three sons of Elizabeth a’Beckett, great-grand-daughter of A.B. Balcombe, gifted the Homestead and surrounding eight hectares jointly to the National Trust and the Mornington Peninsula Shire in 1976. The remaining 225 hectares of the a’Beckett land were purchased by the Shire in 1978.

The homestead is open to the public. Guided tours are conducted through the building and its immediate surrounds to get a feeling of life in a by-gone century.

There is also an unexpected dimension. The link between the Balcombe family and the French Emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte, during his final years in exile, is apparent in a collection of Napoleonic relics collected by A.B. Balcombe’s grand-daughter Dame Mabel Brookes and displayed in the homestead.

References

- Billis and Kenyon: Pastoral Pioneers of Port Phillip.

- [Dame] Mabel Brookes’ books: Riders in Time, Memoirs and Crowded Galleries

Resource material held by The Briars including:-

- The Briars Conservation Analysis Report 1984 prepared by Allom, Lovell & Sanderson for the National Trust

- The excellent research papers of Briars’ Homestead volunteers, Keith & Shirley Murley, especially their detailed studies of family history and Balcombe properties.

- Richard Howitt: “My walk to Western Port and Cape Schanck 1843” from Australia: Historical. Descriptive, and Statistic (1845) p.144

- All photos are from the collection held by The Briars and are reproduced with the permission of The Briars and the National Trust.