Arthurs Seat has been the scene of two RAAF aircraft crashes. The first was an Avro Anson A4 on 10 August 1938, resulting in the loss of four lives and only one survivor. The second was a Bristol Beaufort A9-64 on 12 July 1942, with all four crewmen killed. This is the story of the Avro Anson crash.

On 10 August 1938, five RAAF Avro Anson A4 bombers from No. 2 Squadron based at Point Cook were on navigational exercises.

The aircraft followed a short triangular course with Port Phillip, Western Port and the Gellibrand lighthouse at Williamstown as the three points.

Due to worsening weather, the bombers had been recalled to Point Cook and four had landed.

Mid-morning the air force was given the tragic news that A4-29 had crashed into the northwestern face of Arthurs Seat. Four men had been killed and one had miraculously survived.

At 9.45am, while flying in low cloud over Arthurs Seat, A4-29 had mysteriously crashed into the 300-metre high hillside.

The front of the aircraft was completely demolished after ploughing through trees, but the tail and mid sections were reasonably intact.

The survivor was the turret gunner, James Glover, who was in the rear half of the aircraft. Aircraftsman Glover, a 31-year-old rigger from Hawthorn, had sustained abrasions and was in severe shock. He was admitted to Dromana Bush Nursing Hospital.

Killed were Pilot Officer Stanley Robert Symonds, aged 22 years, of Adelaide; Flight Sergeant John Mahon Gillespie, 28, of St Kilda; Aircraftsman Kenneth Campbell McKerrow, 23, of Carnegie; and Aircraftsman Robert Windram Mawson, 28, of Turramurra, NSW.

Their deaths brought to 10 the number of airmen killed that year, a record in peace-time Australia.

A dense fog and drizzling rain limited visibility to about 30 metres (100ft) on Arthurs Seat when the plane roared in from the sea. Lopping the tops of the taller trees with its wing tips, the bomber crashed about 200 metres (600ft) up the hillside.

The crash was heard by residents of Dromana about six and a half kilometres (four miles) away.

Men working on the main road only 400 metres from the scene were first to reach the wreckage, about four minutes after the crash.

They found the pilot dead and three other men unconscious near the Anson. A fifth member of the crew was seen struggling from the cabin.

The first to reach the plane, G J Griffiths, said that he saw Glover emerge from the gun turret, struggle through the wreckage of the observation cabin, and stagger to the side of one of the men lying on the ground. Glover was suffering from abrasions and severe shock, and was bleeding profusely from a cut on his chin.

Nothing could be done for the three unconscious men, and they died within 10 minutes without having regained consciousness. They were pronounced dead by Dr A J MacDonald, of Dromana, who arrived 20 minutes after the accident.

Mr J Webb, who was working lower down on the mountain, about 1200 metres from the crash scene, said he heard an aircraft above him, but it was obscured by low clouds.

He said the Anson suddenly appeared through the cloud and was flying inland. A few seconds later he heard the crash and hurried to the wreck.

Another eyewitness, Robert Williams, said he heard the aircraft flying low south of Dromana at about 9.45am.

Fragments of the plane were scattered along a path the Anson had torn through the trees for a distance of 125 metres.

The cabin, built of fabric on a steel frame with celluloid windows, took the full force of the crash and was almost completely crushed. This was where the four men had been seated.

The four bodies were found where they had been flung in the direct line of flight of the bomber. The pilot’s body had been hurled more than 30 metres from the aircraft. A second man was found 15 metres in front of the wreckage, another about 10 metres away and the fourth was lying near a tree almost next to the aircraft.

Instruments from the cabin, including the wireless, were scattered about seven metres from the wreckage.

The starboard engine was flung about seven metres after the Anson struck the ground, and the port engine had been stopped by a tree about three metres behind the cabin.

Pieces of the wings hung in the treetops further down Arthurs Seat.

One indication of the terrific speed with which the bomber hit the ground was that boots worn by the dead men had been ripped off their feet.

Broken branches indicated the Anson had struck trees more than 100 metres from where the wreckage lay.

Early inquiries into the crash revealed there was no engine trouble or structural fault in the bomber.

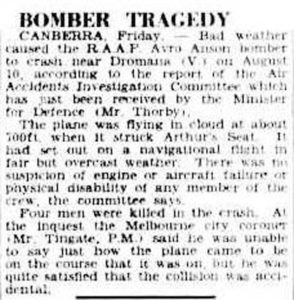

Minister for Defence Harold Thorby, after expressing his regret at the accident, said that the RAAF Air Accidents Investigation Committee had reported the engines of the bomber were running immediately prior to the crash and there was no sign of engine failure having occurred.

“It was a most tragic accident,” he said. “On the facts, as they have been reported to me, it appears that no defect of the machine was responsible. It was sheer bad luck.”

Direction finding equipment was installed in the plane, but it was later shown that the pilot had not called for a bearing.

Members of the investigation committee arrived at the crash site within three hours of the disaster.

They inspected the wreckage, interviewed the men who reached the site first, and spoke to Glover at Dromana Bush Nursing Hospital.

It was reported in the press the next day that because the men’s shoes and parachutes had been removed and the emergency raft had been inflated the pilot must have thought he was flying over water.

This theory was later discounted by members of the investigation committee.

They said the raft had automatically inflated when the aircraft crashed and shoes had probably been torn from the men’s feet when they were hurled through the roof of the cabin.

Official details of the flight of RAAF bombers from Laverton were made public a few days after the crash.

It was officially reported to the Air Board that five Avro Anson bombers attached to No. 2 squadron at Laverton had been engaged in a navigational reconnaissance course.

After the first “circuit”, it was intended to repeat the exercise with the second pilot of each crew in control, but owing to weather conditions near the completion of the first exercise, the bombers were recalled. The plane that crashed had apparently received the call and was turning back.

A further report to the Air Board after a cursory examination of the wreckage stated there had been no engine failure.

Later it was reported: “It is believed the committee will report that an investigation disclosed no failure of the engines, which were running when the aircraft crashed and no other structural faults which might have explained the accident.

“The committee has been unable to determine whether the altimeter was operating efficiently, because it was smashed in the accident. The committee is likely to suggest that the pilot of the machine was not aware that he was flying over land immediately before the crash, and that the low clouds were probably responsible for the course the plane was taking.”

At the inquest conducted by Melbourne coroner Mr A C Tingate, Aircraftsman Glover said the Avro Anson bomber left the airbase at 8.55am.

He was in the rear gunner’s cockpit. Flight Sergeant Gillespie was the pilot and Pilot Officer Symonds was navigator. McKerrow was wireless operator, Mawson was the fitter and Glover was there for general repairs if they were required.

Mr Glover told the coroner he and Aircraftsman Mawson inspected the plane and its engines for efficiency and airworthiness before departure.

(Mawson was the only son of Dr William Mawson and a nephew of Sir Douglas Mawson, the Antarctic explorer.)

Glover said the bomber circled the aerodrome twice to enable the wireless operator to make contact with the ground. The aircraft then headed for Williamstown pier at a height of 2000 feet (610 metres), made a right turn, headed down Port Phillip, and climbed to about 3000 feet (915 metres).

On reaching Point Nepean, the aircraft made a left turn and after having travelled some distance entered a cloud bank.

“The visibility was so bad that I could not see the cabin or outside the plane,” Glover said in his evidence.

“After being in cloud for about four minutes at the normal cruising speed of 130 miles an hour [210km/h] we suddenly emerged. Directly in front of us and only a short distance away I saw trees and a hill.

“I knew a crash was unavoidable and I gripped the seat with both hands. I remember the plane crashing into the trees and the hillside; I was stunned. Later I remember climbing out of the plane, which was badly wrecked

“The four other members of the crew had been thrown out of the plane. I saw McKerrow about 80 feet away. He appeared to be dead. Mawson was about 10 feet away from the plane. He was conscious and said ‘I am pretty bad’. He died in my presence a few minutes later.

“I saw Symonds about 40 feet from the plane. He appeared to be dead. Gillespie was lying about 20 feet from the plane and he appeared to have been killed outright.”

Glover said that up to the time of the crash the plane was flying perfectly.

Rupert Moorehead, an estate agent of Latrobe Parade, Dromana, gave evidence that he was in his backyard with his wife when he heard an aircraft approaching from the sea.

Because of the fog, which was the worst that he had seen for some time, he did not see the aircraft until it was directly overhead. He saw the dim outline of the plane about 50 feet (15 metres) overhead. The aircraft disappeared in a straight line towards Arthurs Seat.

He said to his wife “My God, that plane will crash”. The words were hardly out of his mouth when he heard a crash.

First Constable Holland of Dromana told the coroner that he examined the path cut by the aircraft in the trees. The aircraft had struck light trees at a height of about 25 feet (7.6m) and had continued in a downward direction. Other trees about 18 inches (45cm) in diameter had been broken before it struck the ground at a point 150 feet (45m) from where it had first touched the trees.

After striking the ground, the aircraft had continued on for another 120 feet (36m). Light rain had fallen that morning and Arthurs Seat was enveloped in a heavy fog.

Pilot Officer Gordon Waters Savage, the officer commanding A Flight No 2 Squadron at Laverton, told the coroner he was acting adjutant on the day the aircraft left on its flight.

He produced written orders for the flight and read a statement detailing the course on which the navigator had been instructed to fly. A pilot’s duty, he said, was to pilot the craft as the navigator instructed him.

Mr Tíngate asked: “What happens if they are lost in the clouds?”

Pilot Officer Savage replied: “By the use of the direction-finding wireless bearings they can go right back to Laverton.”

Savage produced a copy of the wireless log. Asked by Mr Tíngate if the crew had asked for their course, he said there was no record of this.

At the inquest, Inspector McMillan assisted the coroner; Squadron Leader Knox Knight, of the RAAF’s No. 2 Squadron, appeared in the interests of the air force; Mr R V Monshan represented the widow and relatives of Gillespie; and Mr F G Marrie represented the relatives of Mawson.

Mr Tíngate found the four occupants were killed when the aircraft accidentally struck Arthurs Seat. “I am unable to say just how the plane came to be on the course that it was on,” he said, “but I am quite satisfied that the collision was accidental.”

The crash caused great consternation around the nation as it was the second air tragedy with multiple deaths that year, the first being near the RAAF’s air base at Richmond in NSW when three airmen were killed.

In the federal parliament, ALP leader John Curtin, who was to become Prime Minister in 1941 during the dark days of the Second World War, called for fuller inquiries into air accidents.

In the federal parliament, ALP leader John Curtin, who was to become Prime Minister in 1941 during the dark days of the Second World War, called for fuller inquiries into air accidents.

He said the Arthurs Seat crash, unfortunately, added force to the Labor Party’s contention that the Air Accidents Investigation Committee should have as one of its members a person with magisterial experience.

“I have always held the view that these inquiries should be open to the public,” Mr Curtin said.

“Failing that, I consider that the presence of some person with cross-examination capacity (other than from within the Department of Defence) would excite greater public confidence in the Air Accidents Investigation Committee and would quash the growing belief that these inquiries merely apply ‘whitewash’ to the department.

“It is certainly remarkable that, despite the number of fatal mishaps to RAAF planes, no statement has been made by the Minister for Defence of corrective measures adopted; there have been no changes (as far as I am aware) in the personnel of those charged with the control of the Air Force and, in brief, nothing has been done which would allay public disquietude as to the state of affairs existing within the Air Force.”

Four good men

PILOT Officer Symonds of Adelaide joined the RAAF in 1937. He entered the Flying Training School at Point Cook in July and graduated in June the following year. He had been transferred to Laverton air station not long before the crash.

Symonds played lacrosse, was regarded as one of the best defenders in Australia and had represented South Australia in interstate games.

After moving to Victoria, he played for Malvern, which won the state premiership in 1937.

The coffin containing the body of Pilot Officer Symonds was placed on the Adelaide Express. The funeral service was held at the West Terrace Cemetery in Adelaide

Before being placed on the train, the coffin was placed on a trailer and covered with a Union Jack on which rested the hat and sword of Pilot Officer Symonds. A mourning party of 35 officers and cadets followed the trailer from the mortuary chapel of E W Jackson in Williamstown to Spencer Street Station.

The Minister for Defence, Harold Thorby, was represented by Squadron Leader A M Charlesworth, while wreaths were sent by Mr Thorby, the Air Board, and from the No. 1 and No. 2 Air Squadrons at Laverton and Point Cook.

Flight Sergeant John Gillespie joined the RAAF in July 1936 and graduated in June 1937. He had 360 hours of flying to his credit in official records.

Full RAAF honours were accorded at the funerals of Gillespie and McKerrow, which were held on the same day.

Gillespie’s funeral was at Melbourne General Cemetery and followed a requiem mass at the Carmelite Church in Middle Park, which was conducted by RAAF Roman Catholic chaplain Flight Lieutenant Chaplain K Morrison.

As the long cortège following the flag-draped coffin approached the entrance to the cemetery, an Avro Anson bomber flew overhead and twice dipped its wings in salute with its motors silenced before returning to Point Cook.

The service for Aircraftsman McKerrow was held at Brighton Cemetery. A firing party was at the graveside, where the service was conducted by Chaplain Morrison, assisted by the Rev Father Dillon.

An RAAF bomber circled high overhead at the cemetery. Earlier, the funeral procession had left the home of his parents in Neerim Road, Glenhuntly. Draped with a Union Jack, the coffin was carried on an air force tender. The cortège, headed by the band of the RAAF, was met at the cemetery gates by a guard of honour, the members of which stood with reversed arms.

The funeral of Aircraftsman Robert Mawson, who was educated at Cranbrook School and Sydney Grammar School, was held at the Melbourne Crematorium in Fawkner.

He was cremated and the ashes sent to Sydney for burial in a family vault.