The original Avenue of Honour in Frankston.

By Peter McCullough

In her book “Echoes from the Front”, Val Latimer tells how as early as 1917 a committee was formed to honour all those from the Frankston District who served in World War One. This was to take the form of an Avenue of Honour along Melbourne Road, now the Nepean Highway. Trees were planted and brass plates were fixed to posts in front of each tree.

By 1957 work was underway for the construction of a new six lane highway: the trees were removed and the plates placed in storage. Of the original 216 name plates when the Avenue was established, only 153 were still in existence when the removal took place.

It was 1997 before the new Avenue of Honour was established, with memorial gardens placed along the centre strip of the Nepean Highway. The new memorial, however, contained 228 names and there were many other “locals” who were not listed; Mrs Latimer’s research found 50 from Frankston and local areas whose families did not respond to the call for names to be included when the Avenue was being planned.

The Avenue of Honour in Frankston as it is today.

On the other hand, the legitimacy of some of the names submitted could be questioned. Were they really volunteers from the Frankston district? Several lived elsewhere but played football for Frankston, while some, such as Montague Romeo, lived in Hastings but worked in Frankston. And that brings us to the Bartram family: all four Bartram boys enlisted and three were killed. Their brass plates are a feature of Frankston’s Avenue of Honour.

The Bartrams

The Bartram boys were born in Richmond, sons of George Andrew and Isabella (nee Shands). All four enlisted in Melbourne, presumably at the Town Hall. Isabella died in August, 1915 aged 57 and in October the following year George and two of his daughters were residing at a new address: “Clare”, in Gould Street, Frankston. So, although technically they were not Frankston citizens, when the call went out for nominations for the Avenue of Honour, the names of the four boys were submitted by the family.

As the heading indicates, 1917 was a horror year for the Bartram family as three of the boys were killed and the surviving brother was invalided home with spinal meningitis. This is the story of the sons of George and Isabella Bartram:

Private Arnold Roy Bartram.

Bartram, Arnold Roy (Private). Service No. 2304: Arnold was 21, single, a shipping clerk, and living at home (9 Hull Street, Richmond) when he enlisted on 6th June, 1916. An earlier attempt to enlist had been unsuccessful on the grounds of “chest”; in the early years the army required a chest measurement of 34 inches at least. Private Bartram embarked with his brother, Cyril, at Melbourne on HMAT A67 Orsova on 1st August, 1916 with the 58th Battalion 4th Reinforcements, arriving at Portsmouth on 14th September. On 6th December he left Folkestone for France to reinforce the 60th Battalion where he was taken on strength on 5th January.

HMAT A67 Orsova.

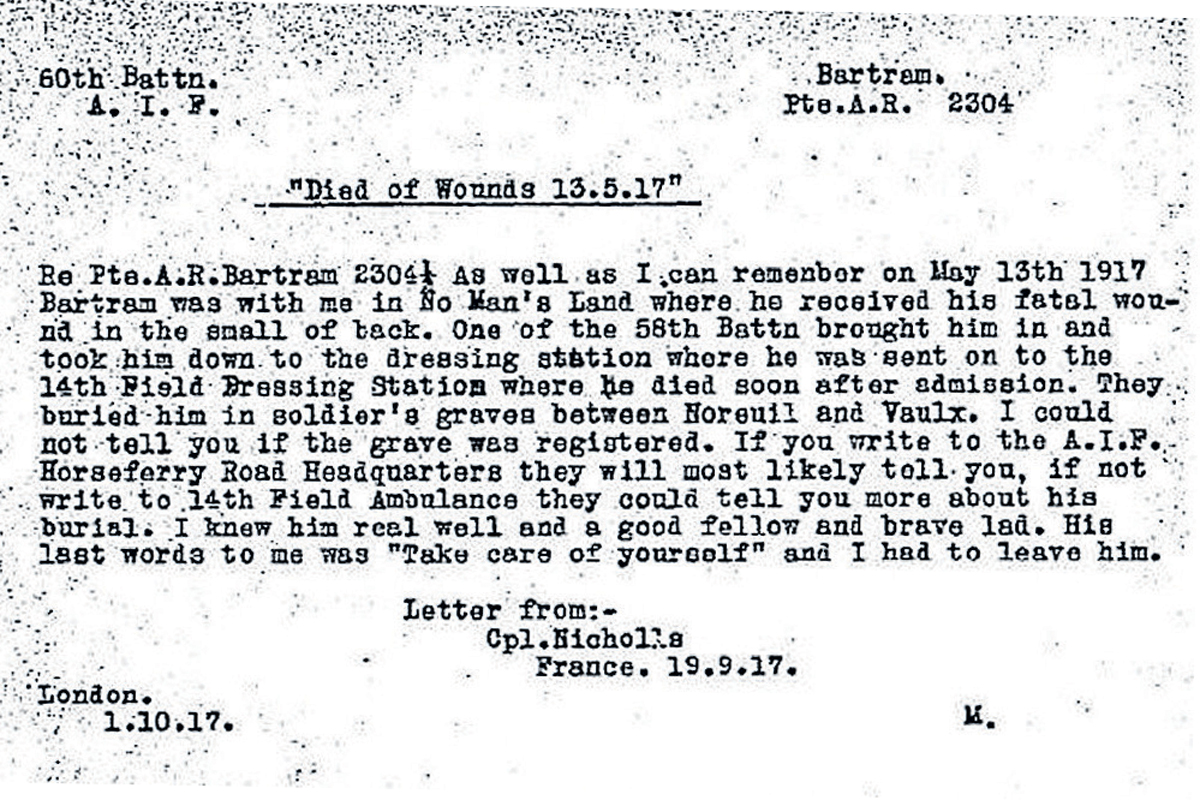

On 12th May, 1917 Private Bartram was recommended for special recognition: “At Bullecourt on the evening of 12th May, Private Arnold Roy Bartram displayed conspicuous courage and devotion to duty. Rendered valuable assistance in carrying in wounded from No Man’s Land when under very shellfire, without the least regard to his own safety. This deserves special recognition.” The recommendation was not gazetted.

On 13th May, 1917 Private Bartram, still only 21, died from a gunshot wound to the abdomen. From reports he was getting into a shell hole at Bullecourt to help a wounded man when he was shot by a sniper and died the next day. He was buried at Grevillers British Cemetery 1½ miles west of Bapaume.

A letter from Corporal Nicholls verifying the death of Private Arnold Roy Bartram.

On 26th May 1917 the family death notice appeared in the Argus and concluded with the inscription: “Fearless minds climb soonest unto crowns.” However, as sometimes happened in these tragic times, a mistake occurred involving Private Bartram which, for a time, would have given his family false hopes. A report in the Mornington Standard on 3rd November, 1917 stated: “It has been officially reported through the Red Cross Bureau that Private Arnold R. Bartram, “Clare”, Gould Street, Frankston (late Manager of Wine, Spirit and Tobacco Department, Mutual Store) is a POW in Germany. He was previously reported died of wounds at 29th Casualty Clearing Station on 13th May, 1917.” This report appeared shortly after the death of brother Reginald and two death notices which appeared in the Argus, only days apart, illustrate the confusion which existed. Late in October Cyril, by now back in Melbourne, inserted this notice:

BARTRAM – In proud and loving memory of my brother, Reg., killed in action 4th October, and of Arn., killed at Bullecourt, and Ray, killed at Messines. “Three very gallant gentlemen.”

On 3rd November, the same day as the report in the Mornington Standard, the following notice was placed by “devoted sisters” Ethel and Clarice:

BARTRAM – A token of love in the memory of our dear brother, Cpl. Reginald Percy who was killed in action on 4th October, 1917, brother of Raymond Everard (killed in action 7th June, 1917) and Arnold Roy (prisoner of war).

Nobody knows how much we miss them;

How much of love, and life, and joy

Has passed on with our darling boys.

At night in a beautiful dream they will come

And visit us all at the old dear home;

Unknown to their loved ones they will stand by our side,

And whisper the words “Death cannot divide.”

Grevillers British Cemetery, the final resting place of Private Arnold Roy Bartram.

In due course the report in the Mornington Standard was withdrawn and the family accepted that Arnold had been killed at Bullecourt.

Later his sister, Ethel Muriel Bartram of “Clare”, Gould Street, Frankston wrote in the Roll of Honour particulars that her brother had been a private in the Yarra Borderers Citizen Forces for three years before enlisting. Among his duties was being a Permanent Guard at the Domain.

In March, 1918 the family received Arnold’s effects which arrived on the Marathon: “identity disc, religious medallion, stylo pen, pipe (damaged), razor, 2 badges, 6 coins, compass on wrist strap, chevron, testament, 2 wallets, photo, cards, lock of hair, charm.”

Two of Arnold’s sisters, Ethel Muriel and Clarice Edna, were named as joint beneficiaries of his will. Be that as it may his father, George, was granted a pension of one pound a fortnight as from 26th July, 1917. This was increased to two pounds a fortnight as from 1st September, 1917.

By 1922 Arnold’s father had received his medals, plus the Memorial Scroll and Memorial Plaque.

Private Cyril George Bartram.

Bartram, Cyril George (Private). Service No. 2126: Cyril was the “lucky” brother – that is if you can call being invalided home with spinal meningitis as being “lucky.”

Born in Richmond, Cyril gave his father George as his next–of–kin when he enlisted on 1st May, 1916. At some point over the next few months he married Eliza MacGregor Murray and was living with his new wife in Gillies Street, Fairfield when he embarked. Cyril was 26 and a manager at the time of his enlistment.

As mentioned earlier, Cyril and Arnold embarked on HMAT A67 Orsova on 1st August, 1916 with the 58th Battalion 4th Reinforcements, disembarking at Plymouth on 14th September. Cyril’s health had deteriorated during the voyage and he was admitted to the military hospital at Devonport on his arrival.

By January, 1917 Cyril was “dangerously ill” with influenza. During convalescence he developed spinal meningitis and left for Australia on the Demosthenes on 27th July, 1917. After arriving home on 24th August, Cyril was discharged from the AIF on 26th October, 1917.

Cyril was not eligible for the 1914-15 Star Medal, nor the Victory Medal as he did not serve in a theatre of war. However he was sent the British War Medal but this was returned in May of 1923; perhaps it had been sent to the wrong address? On 17th July, 1924 it was again despatched – this time to Gillies Street, Fairfield. Cyril must have recovered reasonably well from his illness for he was elected to the Sandringham Council and became mayor in 1928. Cyril and his wife had no children but adopted the three sons of Reginald who was killed in October, 1917: Ernest George (born 1906), Reginald Arthur (1908), and William Blockley (1910). The youngest of these boys died in 1925 aged 15. Cyril’s wife, Eliza, died in 1942 aged 51 but Cyril lived until January, 1947 when he died at Caulfield, aged 57.

Sergeant Raymond Everard Bartram.

Bartram, Raymond Everard (Sergeant). Service No. 2682: Also born in Richmond and living at home with his parents in Hull Street, Ray, as he was generally known, was the first brother to enlist – on 3rd July, 1915. He had attempted to enlist earlier but had been rejected because of dental problems. He was 21, single and a machinist. On 15th September 1915 he embarked at Melbourne on SS Makarini as part of the 8th Reinforcements of the 14th Battalion.

In October, 1915 Ray was admitted to hospital in Heliopolis “dangerously ill” with appendicitis. Two months later he was again back in hospital in Luxor, again with appendicitis. In January, 1916 he was taken on strength with the 46th Battalion and was again hospitalized in Egypt with “pains in the groin.”

In March, 1916 Ray blotted his copybook for his record states:

“Crime: Pilfering goods at Abu-Sueur Railway Station of 30.3.16. Award: Awarded 14 days detention by CO 46th Battalion AIF at Serapeum 4.4.16. Forfeiture of 14 days pay.”

By 8th June Ray had joined the BEF in France. In July, 1916 the 46th Battalion occupied the Front Line at Sailly-le-Sec and the following month participated in the Battle of Pozieres. In October Raymond was admitted to hospital on several occasions with “septic hands.” His earlier misdemeanour notwithstanding, he was promoted to Corporal in December, 1916, and then to Sergeant on 18th February, 1917.

At the time of his death on 7th June, 1917 Sergeant Bartram was leading a party carrying rations to the front line on the first morning of the Messines advance. A shell exploded killing him and six others. Eye witnesses reported that he was buried at Gooseberry Farm nearby. Later his remains were re-interred at Messines Ridge British Cemetery six miles south of Ypres, Belgium.

On 6th April 1918 the Mornington Standard reported on the 7th Presentation to Frankston Volunteers: “In handing medals to Mr. Bartram, Dr. Plowman made feeling reference to the fact that of Mr. Bartram’s four boys who had volunteered, three had made the supreme sacrifice, and one had been invalided home totally unfit for further service. He (Dr. Plowman) extended heartfelt sympathy to Mr. Bartram in his great sorrow, but felt sure he would take comfort from the fact that his sons had died a glorious death, fighting nobly for Australia, and for our security and honour.” If the death notices printed here are any guide, not all members of the family shared Dr. Plowman’s euphoria. The same deep sadness was reflected in the noticed placed in the Argus on 4th July, 1917:

BARTRAM – Killed in action on 7th May. Sergt. Raymond Everard, second youngest dearly loved son of George and the late Isabella Bartram, and brother of Reg. and Cyril (both on active service) and Arnold (died of wounds) and Evelyn, Ethel and Clarice, – aged 23 years.

Our dear boys, crowned by the glimmer of glittering steel, but dimmed by the weight of tears.

Duty nobly done.

Pozieres, France. View of the very strong concrete redoubt known as “Gibraltar”.

Ray Bartram obviously travelled light for in early 1918 the package of personal effects arrived via the Ulysses: “disc, photos, small book.” In August, 1918 the names of the three Bartram brothers were listed among those who were killed and the family was presented with certificates by the Shire of Frankston.

In his will Ray left his estate to sisters Ethel and Clarice, brother Arnold (who pre-deceased him) and Miss Esther Macdonald of 5 Milton Street, South Preston; quite possibly a sweetheart left behind.

Between 1921 and 1923 his father, George, received Ray’s medals, his Memorial Scroll and Memorial Plaque. George died in 1923 aged 65.

Lance Corporal Reginald Percy Bartram.

Bartram, Reginald Percy. (Lance/Corporal). Service No. 6955: Again, born in Richmond, Reginald was 34, a compositor, married with three sons and living in Florence Street, Moreland. He had married Lucy Mary Boughton in 1905. Known as Reg., he was the last of the Bartram boys to enlist, joining up on the 25th August, 1916.

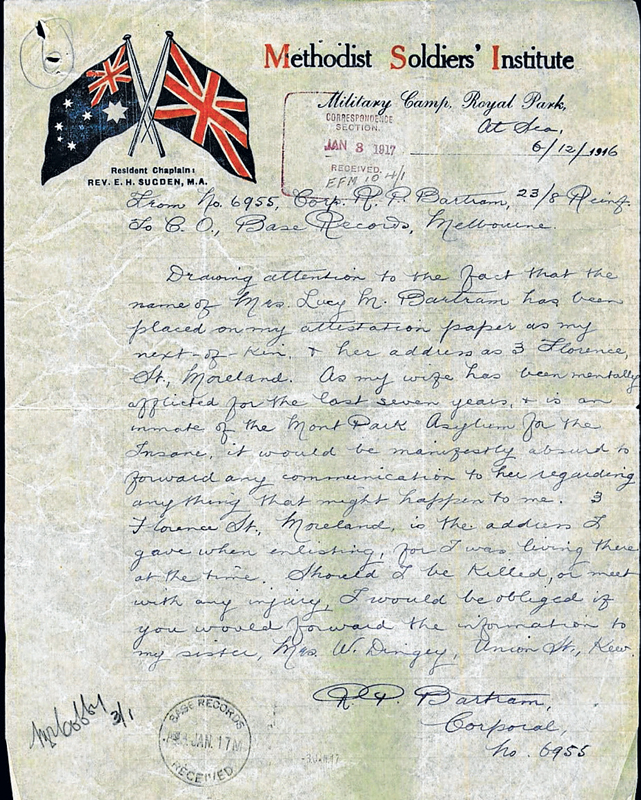

Embarking at Melbourne on HMAT A20 Hororata on 23rd November, 1916 with the 8th Battalion 23rd Reinforcements, Private Bartram arrived in Plymouth on 29th January, 1917. Reg. Bartram’s life was not without complications for, during the journey to England, he fired off a letter to Base Records:

At Sea 6.12.1916 From No. 6955 Corp. R.P. Bartram 23/8 Reinforcements.

To C.O. Base Records, Melbourne.

Drawing attention to the fact that the name of Mrs. Lucy M. Bartram has been placed on my attestation papers as my next–of–kin and her address as 3 Florence Street, Moreland. As my wife has been mentally afflicted for the last seven years, and is an inmate of Mont Park Asylum for the insane, it would be manifestly absurd to forward any communication to her regarding anything that might happen to me. 3 Florence Street, Moreland is the address I gave when enlisting, for I was living there at the time. Should I be killed or meet with an injury, I would be obliged if you would forward the information to my sister, Mrs. W. Dingey, Union Street, Kew.

R.P. Barton Corporal No. 6955.

Subsequently his war records were amended to indicate that his war medals were to be sent to his son at the Kew address. This information notwithstanding, when Lance/ Corporal Bartram’s personal effects were despatched on the Barunga on 20th June, 1918 they were addressed to Mrs. L. Bartram, 3 Florence Street, Moreland. This was in spite of the fact that the aunt, Mrs. Dingey, had written requesting that any effects be sent to the sons at her address. The effects consisted of: “disc, belt, photo case, letters, notebook, cards, book of views, badges, testament.”

As it turned out there was no dispute as to the destination of the effects as the Barunga was lost at sea. However, the war pension records show that “Lucie” (Lucy) of Mont Park Asylum was granted two pounds a fortnight as from 23rd December, 1917.

The Menin Gate at Ypres.

The address of her sons was recorded as “Melbourne Orphan Asylum” and two of them were granted pensions: Ernest George 20 shillings a fortnight and Reginald Arthur 15 shillings a fortnight. Presumably the third son was considered too young to draw a pension! As it turned out, Lucy lived until well into her ‘80’s, dying at the Ararat Asylum in 1964.

In his will Reg. left his estate to be held in trust for his three sons until they reached the age of 21. Although the boys were subsequently adopted by Cyril and his wife, the will appointed as guardians his sister (Evelyn Constance Dingey) and her husband (William Dingey) who were permitted access to the capital for each son for “his maintenance, education or advancement in life.”

Lance/Corporal Bartram was killed in action on 4th October, 1917. From reports to the Red Cross, he was making an advance at the time of his death, having just gone over the top at Passchendaele Ridge. One eyewitness said that he saw a burial party, drawn from the 40th Battalion, burying him later that day. It was in the open, near a German pillbox, and about 1½ miles from Passchendaele Ridge.

A letter from Reginald Bartram to Base Records explaining his wife’s mental state.

Lance/Corporal Bartram’s remains were never found and his name is on the memorial panel 127 at the Ypres Memorial (Menin Gate) in Belgium.

With the large number of casualties, it was possibly inevitable that the occasional error would occur. This happened to the last of the Bartram brothers to be listed as KIA and drew a blunt response from brother Cyril who was still convalescing and no doubt inclined to be a bit testy:

“Clare”, Frankston. 16.11.17.

Base Records, Melbourne.

I notice in Casualty List No. 352, as published in the “Herald”, “Age”, and “Argus” you have inserted my brother’s name: 6955 A/Corporal R.P. Bartram as A/Corporal R.P. Bartman. In view of the sacrifices our family has made, surely we are entitled to expect your reports to be accurate.

I will thank you to publish a correction.

Yours faithfully,

C. Bartram.

From Base Records came a chastened reply:

5th December, 1917.

To Mr. C. Bartram, “Clare”, Frankston, V.

Dear Sir,

In reply to your communication of 16th instant, with reference to the name of your brother, the late No. 6955, Acting Corporal R.P. Bartram, 37th Battalion having been incorrectly spelt in Casualty List 352, I have to state the error which is regretted and which escaped the detection of the checkers during a particularly busy period, is being corrected by a corrigendum attached to Casualty List 371.

Yours faithfully, Officer Base Records, Major.

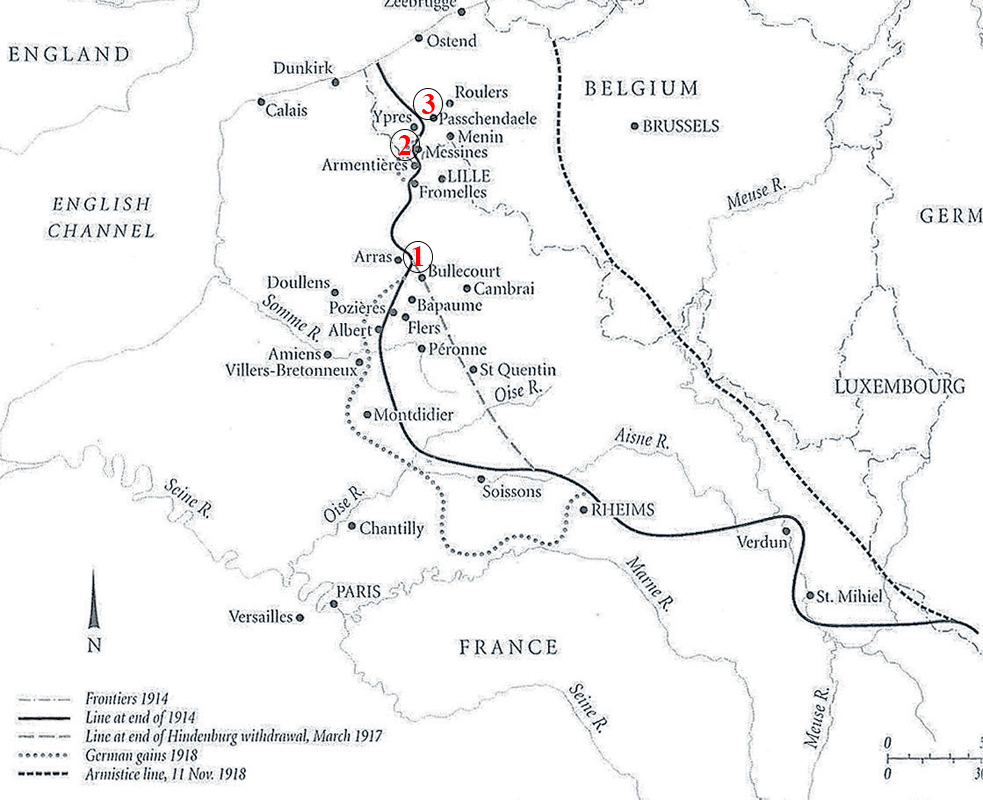

1. Arnold Roy: KIA, 13 May 1917.

2. Raymond Everard: KIA, 7th June 1917.

3. Reginald Percy: KIA, 4th October 1917.

The Western Front – where the Bartrams rest

1. BULLECOURT – Arnold Roy Bartram, KIA 13th May, 1917.

BULLECOURT was the scene of two costly battles for the AIF, the first beginning in the bitterly cold dawn of 11th April, 1917 when, after a night lying in the snow, Australians of the 4th Division were ordered to attack the main German defensive position, the Hindenberg Line. They were supposed to be backed up by British tanks and military, but neither of these eventuated.

Although tanks had been used in the Battle of the Somme six months earlier, they were relatively untested. However, the “mastermind” of the First Battle of Bullecourt (General Hubert Gough) was excited when promised 12 tanks to help break down the German wire and clear a path for the infantry. Only four of the tanks made it to their positions – the others had either broken down, got lost or become stuck in the mud. In fact, the situation provided sufficient material for a Monty Python comedy sketch. At one point a tank lumbered up to the Australian line, turned, and began firing its machine gun at them. After a chorus of shouts from the Australians a hatch opened in the side of the tank, and the head of a British officer appeared, asking which troops they were, and could they please re-direct him to the German lines! Duly instructed, the tank set off only to be destroyed by a shell minutes later.

A tank after coming to grief at Bullecourt.

When the Australians did advance, they were cut off by German artillery and machine guns. After ten hours a withdrawal was ordered, and the surviving Australians had to fight their way back to their original positions. The two brigades involved – the 4th and the 12th – had lost 3,300 men between them, including 1,170 men taken prisoner. This was the largest number of Australians captured during a single engagement in the war, and was exceeded only when Singapore fell in 1942. The battle was later used by the British staff as a model of failed planning.

The Second Battle of Bullecourt, from 3rd – 17th May, was somewhat better planned. The 2nd Division was to take the German positions in the village of Bullecourt and they succeeded using 96 Vickers machine guns and the tried and tested artillery creeping barrage; an offer of tank support was pointedly declined! Even with better planning, the attack cost the three Australian Divisions (1st, 2nd and 5th) another 7,000 casualties. And the gain? Less than a mile.

Resting in the trench at Bullecourt.

The Germans suffered similar casualties. The second attack proved that the Hindenberg Line was not impregnable, as the Germans had tried to make out. One very important lesson was learned though. Whenever the Germans lost ground they counter–attacked. This resulted in heavy German casualties – men they could ill-afford to lose. Therefore, whenever the Allies took German positions, they planned for a counterattack and set up machine gun posts accordingly and gave artillery units the required intelligence they needed.

(Footnote: One of those captured on 11th April, 1917 in the First Battle of Bullecourt was Lance/Corporal Reginald Norman Coates (Serial No. 757). A member of 14th Battalion, he was wounded (“metallic fragments in the arm”) and, after a stay in hospital, he saw out the war in Soltau POW camp, being repatriated to England on 26th December, 1918. Reg. Coates was the grandfather of an old school friend – Bill Ford – and I was fortunate enough to be able to chat to him in his later years. Time never diminished his dislike of the tank. – Peter McCullough.)

2. MESSINES RIDGE – Raymond Everard Bartram, KIA 7th June, 1917.

THE Battle of Messines, fought on 7th June, 1917, was the first large–scale operation involving Australian troops in Belgium. The primary objective was the strategically important Wytschaete–Messines Ridge, the high ground south of Ypres. The Germans used this ridge as a salient into the British lines, building their defence along its ten mile length. Messines was an important success for the British army leading up to the Third Battle of Ypres, culminating in the Battle of Passchendaele several months later.

For years Australian, British and Canadian miners had engaged in subterranean warfare digging an intricate tunnel system under the enemy’s front line. These tunnels were packed with massive charges of explosives designed to obliterate enemy defences. More than 1,000,000 pounds of high explosive were packed into underground chambers along a seven mile front. The main Australian effort was at Hill 60 and their work was made famous in a book by Will Davies “Beneath Hill 60” and a feature film of the same name. The Hill 60 mine created a crater 60 feet deep and 260 feet wide.

The 1st Australian Tunnelling Company at Messines Ridge.

At 3.10am on 7th June 1917, nineteen powerful mines exploded under the German trenches along the Wytschaete–Messines Ridge. The ground erupted into pillars of fire and earth, instantly obliterating the thousands of German troops above. The German survivors were largely stunned and demoralized due to the great concussion of the blasts, the heavy artillery barrage, and the heavy machine gun fire that now poured upon them. Many German prisoners were taken during this phase

Some 10,000 men were killed in the explosion alone and British troops 400 yards away were blown off their feet. Londoners, including Lloyd George in Downing Street, heard the blast which shook all of southern England. As well as the casualties, the scale of the mine explosions both neutralized the enemy’s guns and disrupted their planned counterattack.

Heavily supported by great volumes of artillery fire, the British troops surged forward to capture the enemy positions. The 3rd Australian Division under Major-General John Monash, entering battle for the first time, was anxious to prove itself worthy of the reputation of the other divisions. The veteran divisions were dismissive of the 3rd and derided their late entry into the war by calling its men “the neutrals.” The 3rd Division had a point to prove. It made a very successful attack, alongside the NZ Division, just south of the Messines village. The other Australian division involved, the 4th, made a follow-up attack later in the day.

Although some fighting continued, the result was virtually decided by the end of the first evening with the ridge being taken and enemy counterattacks repulsed. The village of Messines was captured and pill boxes were isolated and destroyed.

It is generally agreed that the Battle of Messines was the most successful local operation of the war, certainly on the Western Front. This success notwithstanding Allied casualties amounted to 13,500 with 6,800 of them being Australians.

Footnote: There were a total of 21 mines which meant that two mines were undetonated on 7th June, 1917. The details of their precise location were mislaid by the British following the war, to the discomfort of local townspeople. A thunderstorm in 1955 detonated one of the mines with the only casualty being a dead cow. The other mine remained undetected until 2004 when the Daily Telegraph carried a report: “50,000 Pound WW1 Bomb Found Under Belgian Farm.” Modern technology had eventually located the last mine. The farmer was unconcerned: “It’s been there all that time, why should it blow up now?”

3. PASSCHENDAELE (THE THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES) – Reginald Percy Bartram. KIA 4th Oct. 1917

THE Battle of Passchendaele was the final chapter in the saga that was the Third Battle of Ypres, a monumental effort to drive the Germans from the high ground of the Ypres Salient. Passchendaele was meticulously planned and relied on limited infantry advances supported by creeping artillery barrages that would force the Germans from their strongholds overlooking Ypres. Australian troops had played important roles in earlier advances during Third Ypres, attacking at Menin Road and Polygon Wood in September, and Broodseinde Ridge in early October. As mentioned previously, they had been instrumental in sweeping the Germans from one of their strongest defensive positions at Messines Ridge in June, clearing the way for the Third Battle of Ypres to begin.

On 4th October the Australian 1st, 2nd and 3rd Divisions had advanced up Broodseinde Ridge and captured key German positions on the slopes below the village of Passchendaele. The attack had been a triumph, catching the Germans completely off guard and forcing them to fall back on a wide front. Although the attack cost the Australians more than 6,500 men, it is considered one of their finest victories of the war. Now it was time to tackle Passchendaele itself.

The grim conditions notwithstanding, the Australians never lost their sense of humour. On the morning of 4th October a small group captured a German pill box where they found two crates of carrier pigeons. These were intended to keep German commanders informed of progress in the battle; instead a number of them were used to transport messages from the Australians of an obscene and personal nature, particularly pertaining to the Kaiser. The remaining pigeons were plucked and stewed.

The mud made life difficult for everybody at Passchendaele. Stretcher bearers struggle through.

At noon on 4th October the weather changed: rain began to fall which by 8th October had become torrential. The battlefield, pummelled by years of shellfire, became a sea of mud. Unfortunately, the British commander-in-chief, Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig, was not to be deterred. In a war characterized by incompetent decision making, Haig’s call to attack Passchendaele was a standout.

The first advance on 9th October which involved the 2nd Division was not a success and illustrates the great problem of Passchendaele. The previous attacks during the Third Battle of Ypres relied on fresh troops advancing under the cover of accurate artillery fire. At Passchendaele both advantages were absent. The troops were exhausted from the slog through the mud to reach the front line and the artillery became bogged and could not reach its proper positions to support the advance. The quagmire was so deep that field guns needed timber platforms laid on a bed of fascines and road metal. Even then they started to sink after firing a few shells, and soon red flags marked positions where guns had sunk altogether. One soldier told how the march to the front line, which would normally take 1 to 1½ hours, took 11 ½ hours through thigh–deep mud.

The second stage of the advance, the attack on Passchendaele itself, was launched on 12th October and involved the 3rd and 4th Divisions alongside the NZ Division. The troops came under fire from the outset, the limited cover from the weak artillery barrage proving totally ineffective. The advancing troops were struggling in the mud and soon became disoriented and lost touch with the barrage.

The situation was hopeless. The Australians had only taken a few of their objectives and were being decimated by German fire. In the face of mounting casualties, the Australians withdrew. The decision to attack had been ludicrous, the attack itself a disaster. The two Australian divisions had lost more than 4,200 men between them. It was estimated that whereas “ground gained” at Messines cost one man per yard, the cost at Passchendaele was 35 men per yard. One stretcher–bearer described the journey to the Regimental Aid Post as a “terrible undertaking: the distance to be covered was less than 1,000 yards but it took six men, four, five, even six hours to do the trip.” Many of the wounded were drowned in the mud and water.

The Australians were relieved by the Canadian Corps, which spent the next two weeks slogging up the same ridge in the same atrocious conditions with Australians supporting their flanks. Eventually the Canadians captured Passchendaele. Even though it was a “victory” in the sense that the village was eventually taken, the British troops were so weakened by the attack that they were left dangerously exposed to a German counterattack. The Germans exploited this in March, 1918. During their Spring Offensive they swept down the ridge and recaptured Passchendaele.

Acknowledgement: Much of my information has come from “Echoes from the Past” by Val Latimer who has willingly helped to clarify some of the details. Copies of her book can be obtained for $25 from the Mornington Peninsula Family History Society which is located in the Recreation Centre in Tower Hill Road, Frankston. Alternatively, a copy can be posted out if a cheque for $38 is sent to the MPFHS, Post Office Box 4235, Frankston 3199. The phone number for the Society is 9783 7058.