By Lance Hodgins

Early on Tuesday July 9th 1867 two steamer tugs left Sandridge, Melbourne’s port, carrying 200 passengers on a clandestine adventure.

The tugs were each towing several smaller boats to be used in landing their passengers but the destination was unknown. The contract simply called for a destination “at least 20 miles down the Bay” and this vagueness was to avoid being followed by the police.

The passengers were “sportsmen” mostly from the hotels and bars of Melbourne and the world of gambling, rat baiting and prize fighting. Prize fighting was a popular sport of 19th century England but strictly speaking it remained illegal – and so it was in the colonies.

After spending several hours in the southern part of the bay looking for a suitable landing, the tugs chose Capel Sound off Rosebud and began to send the boats ashore with their unsuspecting passengers.

The excursion was to have a tragic ending. Difficulties were encountered in crossing the surf zone and six people lost their lives.

What follows is the story of a tragedy which occurred 150 years ago this month. It takes the reader into the seedy world of the illegal sports of nineteenth century Melbourne and the circumstances which drove some of the participants to their deaths.

The Promoter

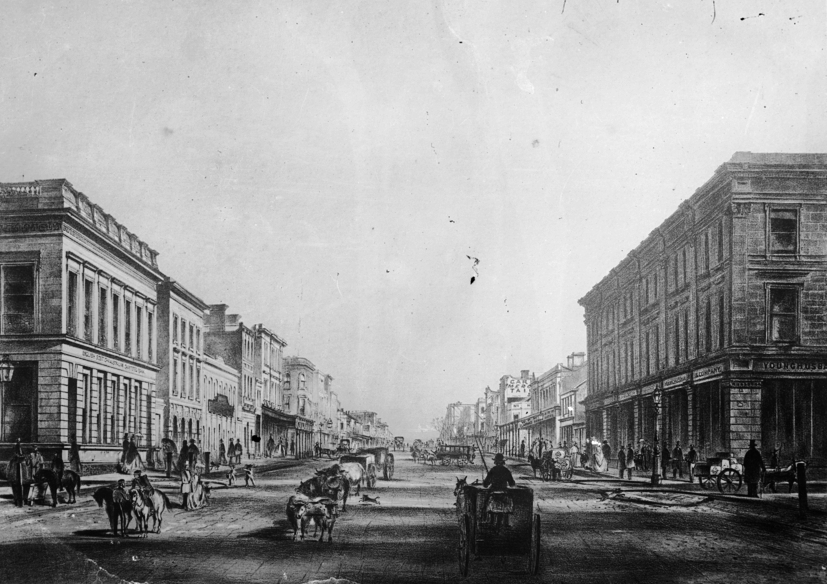

George Strike owned the most famous sporting hotel in Melbourne in the 1860s – the Butchers’ Arms in Elizabeth Street (below). It had no pretensions to be a first class hotel. It was a sporting house where its clientele were immediately recognisable: short, thickset, generally clean-shaven, affecting comforters around the neck as if they had just dropped in during a training run.

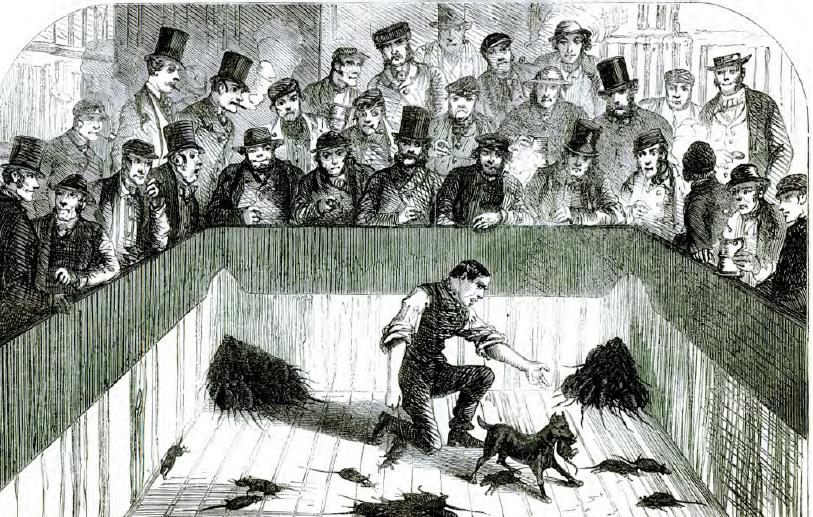

It was the scene of regular ratting matches for which a specially designed rat pit was constructed in mid-1859. It opened with an exhibition of several terriers killing rats against time, and betters were encouraged to back the dog which could kill the greatest numbers of rats in a given time. There were also combats between rats and ferrets, a snake and a mongoose, and on another occasion an echidna was pitted against a dog.

“Rats, Rats, Rats. 200 to be killed in 20 minutes” rang out the poster on the bar window of the Butchers Arms. Once inside, men are everywhere and in the bar the conversation is a lively one about the night’s sport. In a room at the rear of the hotel the seats are arranged as if in an amphitheatre so the spectator can see the whole show without moving from his position.

“Rats, Rats, Rats. 200 to be killed in 20 minutes” rang out the poster on the bar window of the Butchers Arms. Once inside, men are everywhere and in the bar the conversation is a lively one about the night’s sport. In a room at the rear of the hotel the seats are arranged as if in an amphitheatre so the spectator can see the whole show without moving from his position.

The pit is 10 feet by 10 feet and lined with mirrors. Admission fee is one shilling. Strike pays sixpence a dozen for the rats, irrespective of size or colour, which makes rat-catching a profitable industry for some. Butchers, slaughtermen and others employed near the wharves add considerably to their weekly wages by caging rats.

There is a fatty and rancid aroma about the place but there is no disorderly conduct or bad language – only a little chaff, plenty of tobacco smoke and a little betting. There are “swells” in the gallery, racing men who love sport, betting men, smart-looking trainers with the air of a millionaire, jockeys of renown, and people of all nations.

Strike is the eccentric pit-man. He steps into the pit and commences to draw 200 rats, one after the other, from a cage by their tails without being bitten and drop them to their doom. When they are all in, Strike gives the signal “Bring the bitch” and the fun commences.

A 22 pound white bull terrier, “Rosy” is handed in and held and when time is called she goes about her business. Snap, crunch, scrunch, snap, one bite, and it is all over. She wends her way from corner to corner, dealing death and destruction at every grip.

After a couple of five minute rest breaks, during which time the betters furiously negotiate, “Rosy” returns to finish the job with five seconds to spare.

The spectators settle their bets, and then file out to have a drink at the bar and talk about the next encounter.

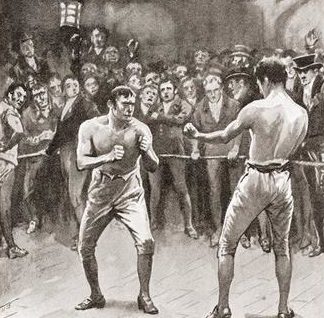

Strike’s pit, however, was not confined to rat-killing. In it he arranged lessons in the manly art of disfiguring an opponent’s face, and many old time pugilists met in the back parlour at Strike’s swapping experiences and, no doubt, lies.

The Butchers Arms became famous as the “pug’s hangout” and prize fighting was always a topic of conversation. Sparring sessions and benefits for prize fighters were held regularly and George Strike, the former London street seller of fruits and vegetables, was invariably the matchmaker and stake-holder for the would-be participants.

Strike had gained considerable notoriety in connection with the prize ring – not as a pugilist, although he was handy with his fists. At every prize fight he was there as a bottle-holder or sponger, or simply as a spectator.

He was not always successful in arranging prize fights. In July 1866 conditions and stake-money were all in hand for a contest between Alf McLaren and George Belcher when McLaren unexpectedly called at the Butchers Arms to announce that he would listen to no proposition from Belcher, and that he would forfeit his money as he was about to leave for Sydney.

He was not always successful in arranging prize fights. In July 1866 conditions and stake-money were all in hand for a contest between Alf McLaren and George Belcher when McLaren unexpectedly called at the Butchers Arms to announce that he would listen to no proposition from Belcher, and that he would forfeit his money as he was about to leave for Sydney.

Twelve months later, however, Strike finalised a deal with McLaren to fight Jack Carstairs – a contest that had the “sporting set” of Melbourne buzzing with excitement.

The Boats Head For Shore

On 7 July 1867 the two tugs and their landing boats headed down Port Phillip Bay to hold the contest. After grounding on Mud Island they turned eastwards towards Rosebud, where they anchored beyond the sandbar of Capel Sound. By that time, however, the wind had whipped up a fairly rough sea and the first two boats containing the organisers and the materials for the makeshift ring barely reached the shore safely. The spectators began to prepare for landing.

The third boat was the Istamboul. The people on board the Resolute had been given confidence by seeing the first boat from the Sophia reach the shore and a boat being towed was brought around from astern for loading.

The Istamboul was a whaleboat 24 feet long, 4 feet 10 inches wide and 1 foot 6 inches deep, and capable of carrying 18 passengers. At the rudder was William “Fifey” Mentiplay, a fisherman well-acquainted with the area while on the oars were the boat’s co-owners, Bill Hayes and James Newman, two watermen with over 50 years experience between them.

Other watermen on the Resolute, however, were not so confident. Alf Holland and George Nichols implored them not to go and, if they did, to not take many passengers. Their advice went unheeded and the Istamboul continued to prepare for its fateful errand.

As the unsuspecting passengers got into the boat it sat considerably lower into the water. Mentiplay was ready to leave as soon as 6-7 were in the boat and said as much. Just then, however, several more jumped in (including the ill-fated Joseph Cheshire and Charles Bramston) which doubled the number. George Jones was already on board.

Young Richard Banner, of the All Nations Hotel, looked over the stern and yelled that this was too many, to which Mentiplay agreed, but some of the passengers thought they could get through and one even said “Well, at any rate, we could swim for it if we had to”.

As they pulled away from the vessel, Mentiplay told the rowers to be careful in crossing the bar. Even after 100 yards he was still cautioning them that they were carrying too many. Newman replied that he had carried that many in the past and it would be alright now.

Mentiplay knew it was too late for them to turn back. They reached the first bar and were soon surrounded by breakers which were “falling over in lumps”. Mentiplay spread out his coat against the rollers but it had little effect, the water rising up over it and half filling the boat from both sides of the stern. It was very clear that once they were in this zone it was impossible to return – the only thing to do was to try and get through it.

Some of the passengers stood up and wanted to bail out the water but were told by Mentiplay to sit down as another wave would swamp them. The men were not drunk, only excited and anxious after the first swamping. The oarsmen pulled away as hard as they could while the water was smooth in between waves and Mentiplay steered straight for the shore as he had done so many times in the past in even rougher conditions.

The boat was now 200 yards from the steamer. The anxious onlookers from the Resolute would see them disappear from sight for about 30 seconds, and then come into view gallantly pulling as the white foam of the surf broke over them.

After a time distance made them so small that their fate became unknown to those on the Resolute. They hoped that they had made it, but there was enough doubt in their minds to discourage any further attempts to go ashore.

The boat was now sitting very deep in the water and it was an easy target when another wave swept over it. Mentiplay found himself afloat and being grabbed by one of the passengers, who was blinded and smothered by his poncho which had been driven over his head. Mentiplay pulled it free and then swam for shore 300-400 yards distant where he scrambled onto dry land – the only one to do so completely unassisted.

The capsized Istamboul was clung to by those dumped into the water. They were doomed by the fact that many of them couldn’t swim and those who could were hampered by the cloaks and great coats they were wearing. Oarsman Hayes advised those who could swim to strike out for shore. Hayes was a good swimmer and he made it to within 10 yards of the beach where he was rescued.

Jeremiah Quinlan, the landlord of the Kilkenny Hotel in Therry Street, was also picked up by a boat while swimming to shore. He told his rescuers he recalled seeing passenger Wollicott also swimming, wearing a poncho. He was washed away a couple of times and brought back by Quinlan. Wollicott called out “What will become of my wife and children?” just before he sank and was not seen again.

This whole episode had been observed by Sawdy, Anderson and Edwards from the shore and they immediately pulled back to the spot and lent assistance.

When Sawdy reached the stricken vessel he passed an oar to Hayes, who was on the point of sinking, and pulled him into his boat.

Sawdy then rescued Ashton, a butcher from Prahran, who was also close to exhaustion. Cheshire and Bramston were nearby but they sank before they could be saved and their bodies drifted ashore.

Edwards picked up three passengers as well and took them to the beach but, in all, five were lost from this boat.

Sawdy and Edwards were later praised in no uncertain terms for their valour in having saved the lives of 14-16 people by their efforts. It was fortunate that they had reached the shore safely in the first place and then could return to render assistance to those in trouble.

Conclusion

Rather than being banned, bare-knuckle prize fighting continued in Australia for another decade.

Rather than being banned, bare-knuckle prize fighting continued in Australia for another decade.

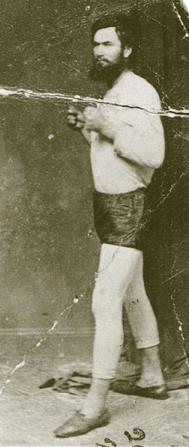

One of its best known proponents was Ned Kelly (right), who fought Wild Wright in a famous bout in Beechworth in 1874. Kelly won after 20 rounds.

Yet, by pure coincidence, the year of the Capel Sound tragedy marked the beginning of the end of the bare-knuckle prize fight. In 1867 a set of rules was put in place in Britain by the Marquess of Queensberry which added some respectability and laid the foundations of the modern sport of boxing.

The deaths at Capel Sound were regarded as collateral damage and, as such, consigned to the relative obscurities of history.

This story is an extract from the book “The Tragedy at Capel Sound” by local historian Lance Hodgins.

Copies are available from the author for $15. Ring Lance on 5979 2576.