By Peter McCullough

Les Streete’s accomplishments were many: he flew Spitfires over Europe towards the end of World War 11, ran in two Stawell Gifts, one of which was the controversial 1947 event, and contributed to many aspects of the Rye community including the establishment of the splendid Rye RSL complex. His most precious possession, which he wore every Anzac Day, was a white scarf made out of parachute silk; it was part of a larger item which saved his life in 1944. Not long before he passed away on 15 April, 2013 I had the opportunity to speak with Les; this is his story.

Early Life

LESLEY Theodore Streete was born at Alstonville, New South Wales, on 12 August 1922 to Albert and Polly. His father was employed by the Post Office (or PMG as it was then known) and Polly was a hairdresser. Les had two younger brothers: Ivan and Cecil.

When the family moved to Lismore, all of the boys became heavily involved in sport. Ivan was a keen bike rider and Les excelled at football, tennis and athletics. He was also a keen boxer and became the Northern NSW featherweight champion, undefeated in 13 bouts.

Les left Lismore High School with his Intermediate Certificate and started work as an apprentice motor mechanic at Robinson’s garage. He would have liked to become a teacher but the family could not afford the additional costs of education.

The War Years

In 1940 Les was called up for the militia and sent to Maitland in NSW. He subsequently transferred to the Australian Imperial Force. When Les was 10 years old his mother had taken him on a joy flight in the Southern Cross flown by Kingsford-Smith. It was at that point that Les decided he wanted to be a pilot. Accordingly, when the government called for volunteers for the Empire Air Training Scheme, Les put in for another transfer.

On 1 January 1943, Les was sent to the 2nd Initial Training School at Bradfield Park where he received a course in ground instruction lasting until the end of March. For his preliminary training he drew Narromine in the north-west of NSW. In May and June of 1943 Les developed a proficiency at flying the Tiger Moth and this was supplemented by many hours of class instruction. The results at Narromine earned Les a place in the advanced training course in Canada.

By 24 August 1943 Les and a number of other Australian pilots had commenced a 16-week course on fighter trainers at No.6 Service Flight Training School at Dunnville, Canada. The planes they would train on were Harvards – worlds away from the little Tiger Moths.

On 10 December 1943, Les was presented with his wings and was posted to an operational training unit at Bagotville in Northern Quebec on the Saguenay River. By February 1944 Les and his colleagues had commenced advanced pilot training in severe weather conditions; proficiency at instrument flying was mandatory. The pilots had now moved on to the faster Hurricanes.

After some formation practice on 20 March 1944 Les was ordered to take his Hurricane to 28,000 feet. At 25,000 feet, without warning, the cockpit began to fill with smoke and fumes. When he noticed flames below his seating area, Les realised he had to get out since a full explosion, totally destroying the aircraft and killing him in the process, was the likely outcome. At 20,000 feet he was still too high to bale out, but the risks of remaining were too great. The lack of oxygen at this height would give him precious seconds before hypoxia would send him unconscious.

Les, putting into practice the drill to leave the aircraft, exited through the open canopy and into the airstream. The bitterly cold air grabbed him and he seemed to lose all sense of time. Then he was brought back into focus as the parachute opened with a jolt. Looking up, Les saw what he considered “..the most beautiful sight I have ever seen; the shape of the silk parachute above me.” Unfortunately the jolt had shaken off one of his boots and the cold was excruciating.

Eventually Les drifted into a cluster of fir trees. His first action was to tear some silk from his parachute to wrap around his foot. With some difficulty Les extricated himself from the fir trees and made his way to a cabin only 100 yards away. There he burst in on two startled French-Canadian women. The ladies gave Les some warm soup, and a sock and shoe to replace the missing boot. While he was waiting to be collected by someone from his base, the ladies busied themselves in sewing a section of the parachute into a scarf. Embroidered, in one corner, in royal blue thread, was an inscription in French; translated it states, “My life saved by this. 20th March, 1944.” After that day Les always flew with that scarf and it received an annual outing each Anzac Day.

Although sabotage was suspected since two other Hurricanes from the base had inexplicably caught fire, Les resumed flight training the next day, and for the next two days he was involved in formation flying and mock attacks. His final training course in Canada was at the No.36 Operational Training Unit at Greenwood (Nova Scotia), a Mosquito base. This course lasted until 2 June.

When Les arrived in England he was posted to No.57 Operational Training Unit at Eshott, Northumberland. It soon became apparent that pilots there were being trained to fly Spitfires, and their training course continued until 3 November. By the end of that month Les had been posted to 66 Squadron where he would fly Spitfires from a base in Belgium.

The Spitfire was a superb fighting aircraft, and by the end of the war 20,334 had been produced. As it happened, Les’s entire combat experience was to be from the cockpit of the clipped wing Spitfire Mark XVI. By late 1944 the days of the big bombing raids and the dogfights were almost over. By then the Spitfire was being used predominantly to strike at targets on the ground. Accordingly, the armaments of the Mark XVI typically consisted of two Hispano 20mm cannons and two .50 inch Browning machine guns. In addition it could be configured to carry 1000 lbs of bombs; a central 500 lb bomb and a single 250 lb bomb slung under each wing. As the drive into Germany entered its final stages, the aircraft was fitted with a number of external tanks to extend its range, bringing targets deep inside Germany within its reach.

Les was based initially at Grimbergen, about eight miles south of Brussels. After some familiarisation flights, Les flew his first mission on 15 December, 1944. Weather permitting, he then flew almost daily until 27 April 1945, generally bombing and strafing enemy troops and equipment. On occasions Les’s squadron provided an escort to Allied bombers. Although most of his success was achieved by hitting ground targets, Les was credited with shooting down four V-1 rockets and several German fighters.

As the Allies advanced 66 Squadron moved to new bases: Woensdrecht, Schijndel, and Rheine. It was then decided to disband 66 Squadron. Of the original 36 pilots, only three were left. By early June Les was back in England learning to fly the latest fighter, the Tempest. In mid-June he received his commission; he was now Flying Officer Les Streete.

Back to Civilian Life

When Les returned to Lismore in September 1945 he was a troubled man. Bad memories flooded his mind: of close mates shot down over Holland and Germany, and of Dutch civilians fleeing when his squadron was ordered to destroy a Gestapo headquarters in North Amsterdam when the building was in fact a transport depot.

Les’s parents were extremely upset by the change to his personality; today it would be diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder. To purge himself from his demons Les threw himself into athletics and then had the good fortune to meet a young nurse (Phyllis) who understood and was prepared to listen. Les and Phyllis married in 1948 and moved to Victoria.

Les had spent time at Rye when training for the Stawell Gift and, with the support of Harry Anderson who had sponsored him in the 1947 Gift, Les and Phyllis bought a mixed business in Rye: it would not only provide a living but a new focus for Les.

Settled in Rye

For a number of years Les and Phyllis worked at their business: summers were particularly hard work when the Mornington Peninsula was crowded with holiday makers. Then someone made Les an offer: a swap of some sub-dividable land in Rye for his business. It turned out to be a profitable venture and Les commenced working in real estate. Phyllis returned to nursing and worked for many years at the Rosebud Hospital. Les supported her with his fund raising efforts for the hospital, and was honoured by being made a Life Governor in 1972.

Not long after settling in Rye, Les became involved in the affairs of returned service men and women. When the Rye sub-branch of the RSL was established in 1951 Les was a foundation member, becoming Secretary in 1957. While the real estate business prospered, Les’s heart was in the RSL. In 1963 he became manager, a post he held until 1987. His service was unstinting and he was awarded life membership in 1971. In 1999 he was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal by the RSL, the League’s highest award.

Les’s community involvement was not restricted to the Rye RSL or the Rosebud Hospital. He played in two premiership teams with Rye Football Club in 1951 and 1954, and was named on the wing in Rye’s team of the decade. He coached the Rye Junior Football Club, was a Foundation Committee Member of the Rye Sea Scouts and was also a Foundation Committee Member of the Fishing, Golf and Indoor Bowls Clubs associated with the Rye RSL.

Les and Phyllis were a happy and dynamic couple who still found the time to raise four children. After a wonderful life together, Phyllis contracted cancer and passed away in 1984. In his later years he enjoyed and appreciated the support and companionship of Margaret.

Les continued to be a valued member of the Rye community, particularly at the RSL. In August 2012 a special function was held to celebrate Les’s 90th birthday. Apart from the enjoyment of catching up with family and friends, there were two other matters which added to the excitement of the evening. The first was the opportunity to launch Peter Fitton’s biography of Les, Never Been Hit.

The second cause of excitement was the surprise arrival of a special guest. When Les was on leave in England he generally headed for London with one or two of his mates, and they were always made welcome at the home of his cousin, Louie. Louie had a young family and Les always enjoyed taking them shopping and to shows. His second cousin, Adrian, was only seven years old when Les last saw him in London at the end of the war. It was a massive surprise for Les when he walked into the Rye RSL club to join in the birthday celebrations.

The Empire Air Training Scheme

BY the early 1940s the war planners in England had foreseen that the number of pilots, co-pilots, navigators, engineers, gunners, observers, bombardiers, and radio operators would grow to a stage where their own training facilities would not be able to meet the demand.

The RAF requirements for the war against the Axis powers would run to 50,000 men per year.

Britain could supply 22,000.

The Empire Air Training Scheme (E.A.T.S.) was designed to make up the projected shortfall, with personnel coming from Australia, South Africa, Rhodesia, New Zealand, and Canada.

Ultimately 37,000 Australians were trained under the E.A.T.S.

Most went to Canada for advanced training, though some were trained in Australia to fighter pilot standard before being sent straight into the squadrons.

Excerpt from Page 21 of ‘Never Been Hit’ by Peter Fitton.

Too close for comfort – Les vs The V-1

THE last day of 1944 would be a busy day for Les. He would fly three missions. Flying LZ-Q in the morning, the Squadron escorted a force of Boston bombers to the Namea area of Holland. This was in central Holland, close to Apeldoorn. It was bitterly cold, but without snow or rain. The countryside almost appeared in black and white tones, with patches of grey, patches of snow and the occasional tint of drab green. At 10.00 hours they linked up with the bombers. It was while the fighters were weaving above them that Les thought he saw something. Signalling to his flight, he moved off towards the object.

It was as small as it was fast. Les only noticed it because of the flame. Since he had arrived at Bergen Op Zoom, these things had been raining down at random. The mission this day was to provide cover to a flight of Bostons. But, glancing around, he noticed that all was quiet; no enemy fighters, no flak, just this unendurable coldness. Les moved his hand to the throttle. At the same time he shoved his spade control over to starboard. The Spitfire nosed over as he peeled away towards the V-1.

The flying bomb was moving across and away from him. Hand still on the throttle, Les squeezed on maximum power. The Packard-Merlin engine bellowed with a growl that reverberated through the airframe. He was at full boost. Two thousand horses were out front and they were screaming to get loose. The four-bladed air screw was in coarse pitch, the maximum twist on the blades. It drew the aircraft forward with a surge that pressed Les back in his seat.

By then all he could see of the V-1 was the little flame coming from its pulse jet. From a different angle it would have been lost to sight. The Germans had painted it well. Its dark grey-green colour made it blend to perfection with the equally dark countryside. It was just that they had not succeeded in masking the flame.

Les looked back towards his flight. They were merely dots against the lighter background of cloud. A look at his instruments. Another glance around. As he did this, it came to him as in class, “Keep a proper watch. Don’t sit looking about. Scan the middle distance, then further away. Move across from left to right. Run your eye over the instruments in between. Check above and keep alert for bandits.”

His airspeed was 380 mph and still creeping up. A little forward pressure on the spade control and the nose of the Spitfire dropped slightly. Les thought, “That’s better.” He needed more airspeed to catch the V-1 and with the slight dive he had his aircraft close to 400 mph. The noise from engine and slipstream was incredible. He was getting closer. A look around. Overhead clear. Nothing in view out the sides. Lift up the safety cap on the circular firing handle.

Reaching towards his dash mounted gun-sight, Les twisted the dial, filling the circular graticule with the image of the V-1. Not delaying, he squeezed off a burst from his two half inch Browning machine guns. The tracers surged forward. They hit but there was no difference. Les took aim again, this time rolling his thumb so that it would press the cannon button as well. Rapid firing 20mm with an explosive warhead. Pressing the trigger, his plane shook and slowed. The smoke spat forward from both wings as Les watched the shells streak towards the quarry. The next thing, the V-1 exploded. A violent eruption of an explosion. No notice. Just bang. The V-1 had seemed so small, yet the violence of the disintegration shocked him. He had forgotten that its payload was nearly a ton. In an instant his aircraft flew through this tangle of fire and wreckage. With a crash, he was through it and into clear sky again. Was he part of the wreckage? His reaction was to sit and wait. A second or two. No. The Spitfire was still under control. But there was a difference. He could feel it. No fire. No loss of control. What then? He banked and headed back to his Squadron and the flight of Bostons.

Back to base. He landed normally and taxied to dispersal. His ground crew came towards him at a trot. They were pointing. It was only when Les climbed out of the cockpit that he could hear their chatter. The propeller spinner had been blown off, yet the aircraft was otherwise undamaged. He walked towards them smiling but could feel the palms of his hands were warm and moist.

Excerpt from pages 121-126 of ‘Never Been Hit’ by Peter Fitton.

Shot Down at Stawell

ON his return to Lismore in 1945, while still dealing with his memories, Les joined the local athletic club where he met Bert Hicks. Bert was a local trainer who had retired from Victoria to be near his two sons. He noticed that Les was quite fast, and told him about the Stawell Gift, Australia’s oldest and richest footrace, which was run every Easter in Victoria. Bert said he had a contact in Victoria, a highly respected trainer named Ron Wilson. So Les entered the 1946 Gift where he was beaten in the semi-final by the eventual winner, Tommy Deane. (Tommy, a young footballer from Tatura, had been trained by the 1933 winner, Goldie Heath from Baillieston East. Heath, running in the Depression years, was attacked on the morning of the final when, according to the official record, “…a vicious attempt was made to kick and injure him. Because of his presence of mind, Heath skilfully evaded the onslaught, and was not lacking in the courage to deal out a little justice for himself.”)

Although 1946 might have been a disappointment, Ron Wilson introduced Les to a Mr Harry Anderson who owned a hosiery factory in Coburg; he said with more experience and proper training he would sponsor Les for the 1947 Gift.

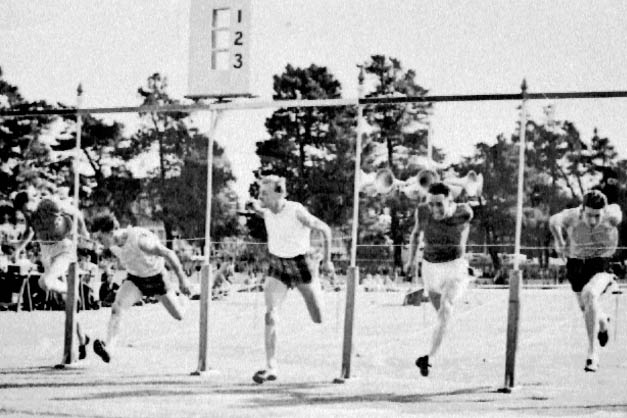

Les trained enthusiastically, often at Rye during weekends as Mr Anderson had a holiday house there. The 1947 final was strongly disputed and is so controversial that it is shown every Easter as part of the TV commentary. These were the days before electronic timing and it was not until 1949 that the first step was taken in that direction with the Draper Electronic Finish Machine. In 1947 the accuracy of the judges was therefore paramount. The only “evidence” is the press photograph which was taken front-on as the five runners hit the finish line.

Les recalled, “I thought I had won it and the judges initially awarded me the race. However further consultation between the judges took place and the decision was overturned, with the two contestants on either side of me (Gardner and Martin) judged to be joint winners. Gardner should have been disqualified as he broke the tape with his mouth rather than his chest. Martin won the run-off later in the day and it was decided that I had in fact run last! According to the rumours that swept through Stawell at the time, one of the joint winners had a close family connection with one of the judges. We thought of taking court action but were told that the judges’ decision was final. I was still only 25 but the events of 1947 killed off my enthusiasm.”

So Les, who had experienced a degree of good fortune in both Europe and Canada, found that his luck ran out at Stawell. The press recorded the proceedings along similar lines to Les: “Within a few seconds of the five runners finishing the race it was announced over the loudspeakers that L.T.Streete of Lismore NSW was the winner. His colour was also registered on the flag standard. The announcement created complete confusion among runners, trainers and officials on the ground and the public close to the finishing line. One minute later the decision was corrected by the announcement that Martin and Gardner had dead heated.”

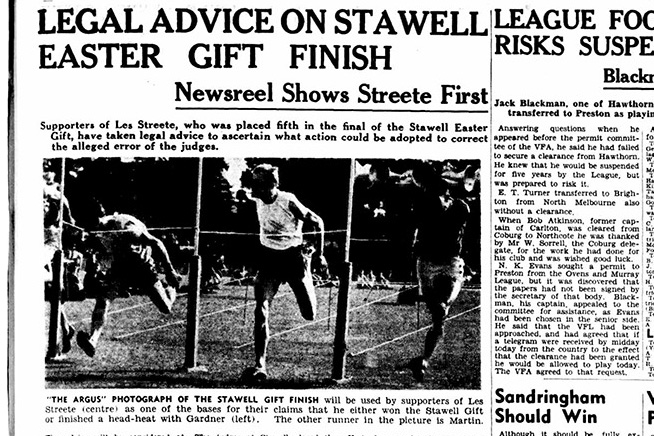

Although Les retreated to Lismore and retired from sprint running, his supporters did not let the matter drop. An item appeared in The Argus on Saturday 12 April 1947, five days after the event.

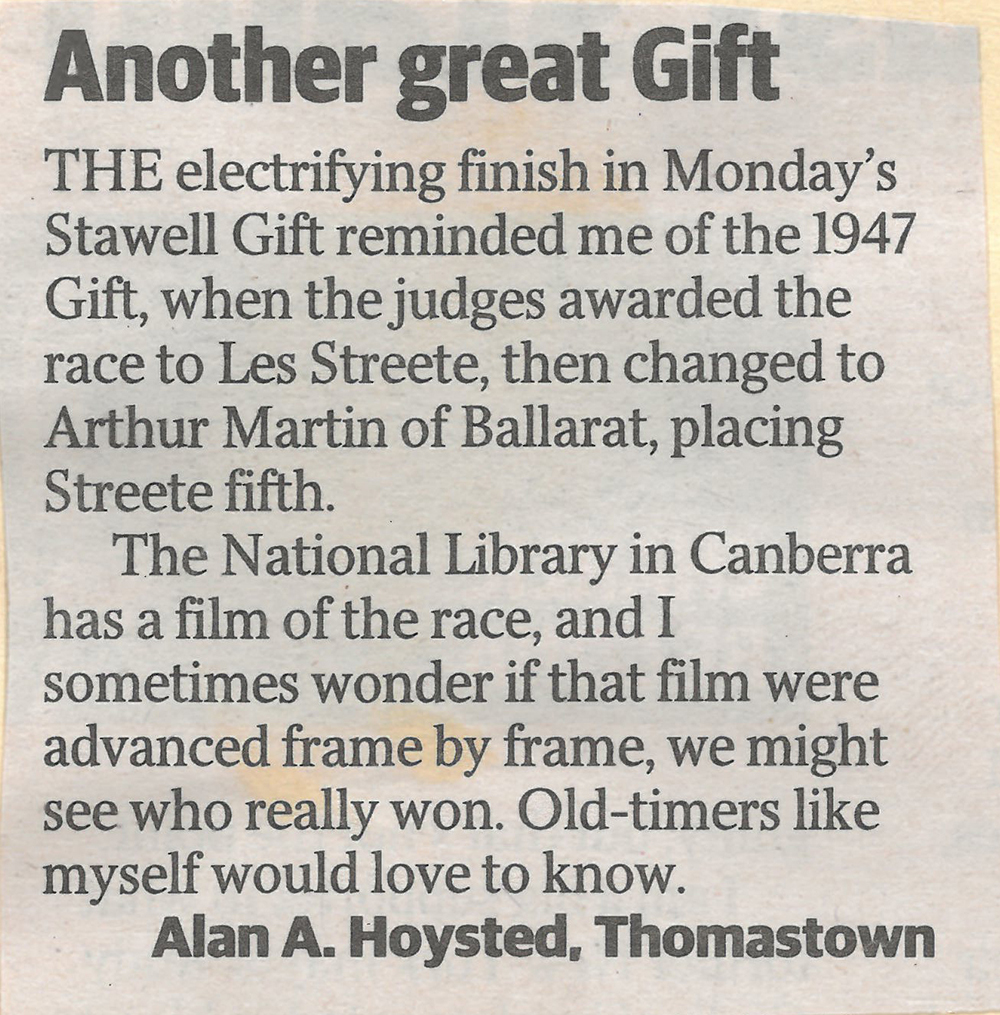

No further action appears to have been taken but that controversial finish has never been forgotten. Several years ago, more than seven decades after the event, the letter alongside appeared in the metropolitan press.

Who knows? One day the authorities might just analyse the film (which can be viewed on the internet) and decide that the original decision was in fact correct.

References:

Fitton, Peter ‘Never Been Hit’, (available on bookdepository.com)

www.neverbeenhit.com

Footnotes:

It would not have been possible to complete this story without the assistance of Les’s daughter, Vicki Higgins, who provided notes and photographs. I have also borrowed from Peter Fitton’s biography and would recommend it to anyone interested in this part of our history.