By Ilma Hackett – Balnarring and District Historical Society

Bushrangers Bay is a spectacularly beautiful section of coastline between Flinders and Cape Schanck. A small isolated beach backed by high dunes lies between towering headlands. A creek winds through the dunes about midway along the bay while a smaller creek drops to the sea near the western end. A rock shelf stretches at the base of the cliffs. It can be reached either by walking along the cliff top from Cape Schanck or by means of a narrow path that cuts across paddocks before dropping down to the sands.

The name, romantic-sounding in this modern era, hints at a dark history. The story is one steeped in violence and bloodshed. It was at this spot, during Colonial times, that two convicts on the run from Van Diemen’s Land stepped ashore.

The whale boat that put into the bay on the night of 19 September, 1853 carried four men. Two were unwilling sailors from the schooner Sophia; the other two were convicts, Henry Bradley and Patrick O’Connor, who had hi-jacked the schooner near Circular Head on the north west of Van Diemen’s Land and forced the captain to take them to the Australian mainland. Once ashore O’Connor and Bradley led the police on a chase that would end the following month with their hanging in the [Old] Melbourne Gaol.

Who were Bradley and O’Connor?

The two men were lifers. They were both about the same age – in their 20s. In 1853 both were assigned to two different landholders in the Circular Head area of northern Van Diemen’s Land before they carried out their planned escape.

Henry (Harry) Bradley, a native of Blackburn, Lancashire arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1846. He had been sentenced in Liverpool and transported for ten years for ‘housebreaking and stealing wearing apparel.’ He was then twenty years old, a short man of fair complexion with longish, curly, brown hair. His face was thin, his nose had unusually wide-nostrils and he was clean-shaven. A number of tattoos adorned both arms including one below his left elbow that read “in Remembrance of my Mother”.

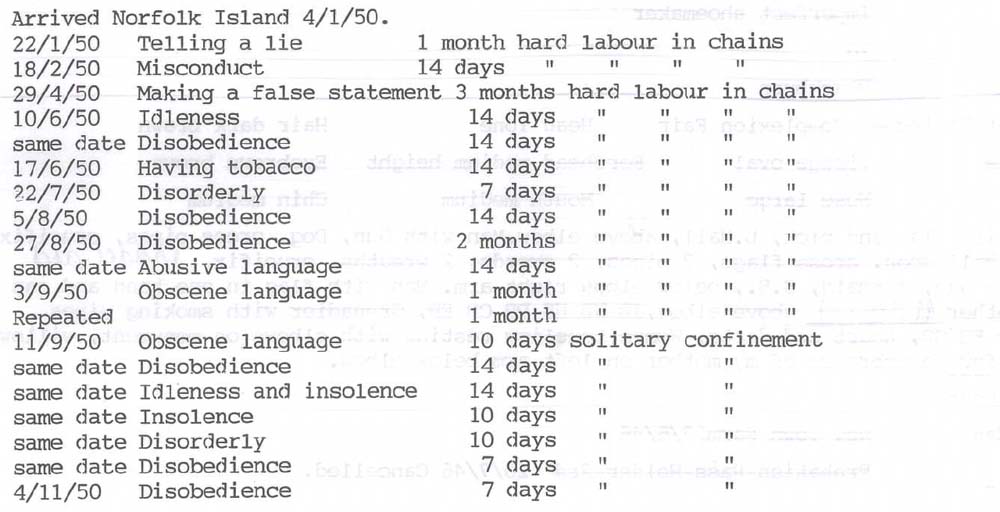

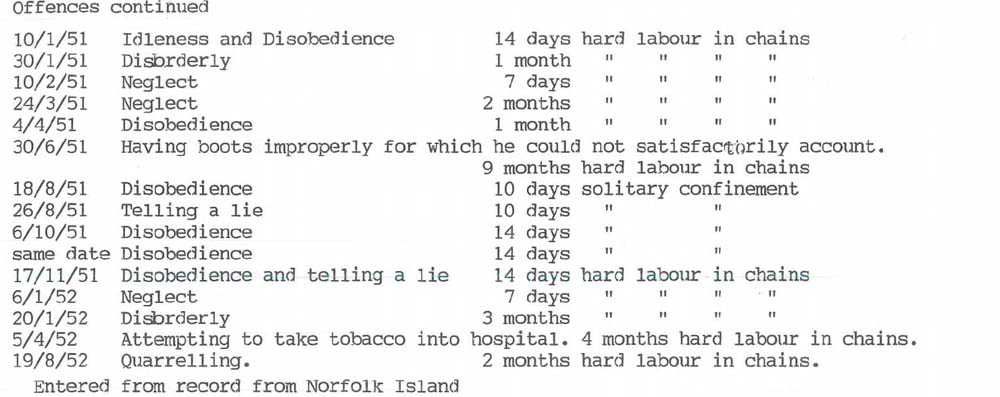

One story is that he had been orphaned when still a lad and had survived by joining a gang of pickpockets which lead to him spending time in prison. His convict record shows he had been “an imperfect” shoe-maker, i.e. an apprentice, a trade he had learnt when in custody on the Isle of Wight. He was able to both read and write “a little”. The first part of his probation period in Van Diemen’s Land was spent with a work gang at Newton Farm but he repeatedly offended, his sentence being extended each time until he was finally given a life sentence for assault and robbery. Bradley was sent to Port Arthur towards the end of 1847. His misconduct there (a long list including disobedience, obscene language, assaulting a fellow prisoner, absconding) saw him being transferred to Norfolk Island where he spent almost three years. Even there his record was hardly exemplary. In 1853 he was returned to the Prisoner Barracks at Launceston then assigned to civilian, George Kay in the Circular Head district. Kay became responsible for feeding and clothing the prisoner and paid him a wage in return for his labour.

His companion, Patrick O’Connor had been transported to Van Diemen’s Land in 1850 from Adelaide where he had been convicted of “attempted highway robbery”. Not much is known of his early record before he came to Australia. An Irishman from County Galway, O’Connor claimed at one time that he had come to South Australia as a free immigrant and had fallen foul of the law. However it seems likely he had spent some time in prison in England before being sent to Australia. He narrowly missed being convicted of the brutal murder of an elderly man on a sheep station inland from Adelaide. The victim, Tom Roberts, had been stabbed several times in the back and shoulders and shot twice. O’Connor was pursued but no conviction was ever brought against him for this murder. However near Salisbury he attempted to hold up the mail coach and was finally taken into custody after a chase that took two days and covered one hundred and fifty miles. He was charged with robbery with violence and received a life sentence. O’Connor was one of four male convicts transported to Van Diemen’s Land from Adelaide on board the schooner, Deslandes. His records show he was 20 years old in 1850, five feet eight inches tall and of powerful build. Like Bradley, he was fair complexioned; his hair was red and he wore whiskers and a moustache. A scar marred his nose, one of his front teeth was missing and his arms were freckled. It was noted that he was Roman Catholic and literate.

O’Connor had spent time at the Cascades Probation Station on the Tasman Peninsula before being transferred to the northern part of Van Diemen’s Land and assigned to Mr Alford near Circular Head in June 1853. At that time Bradley was on a nearby farm. Both were well paid but freedom beckoned and together they had hatched a plan to escape.

Escape from Van Diemen’s Land

On the night of 14 September, 1853 they implemented their plan, striking across country towards Circular Head, a section of coastline from which many small trading vessels left for Victoria. At the first two huts they raided they tied up those inside and took double-barrelled guns. Armed with the shotguns they went to the homestead of John House, who they mistakenly believed would have a large sum of money on his premises. They tied together Mr House’s man-servant and Alfred Phillips, a relative of House’s who had heard the disturbance and had come to the door. House, hearing the fracas, escaped through his bedroom window and ran to seek help. He was fired at but the shots went wide. Frustrated, O’Connor shot and killed Phillips.

The hue and cry was raised as the pair continued to pillage their way towards Circular Head. Several workers’ huts and farm houses were raided for food, more guns and ammunition. Near Table Cape they came upon a police constable and a mail carrier from Emu Bay who had retrieved mail from a wrecked schooner. The constable challenged the pair and was shot in the arm before he and his companion managed to elude the bushrangers by disappearing into the darkness of the scrub.

On 15 September, heavily armed, they tricked their way aboard the schooner Sophia which was anchored in the River Inglis, loaded and ready to set sail. Several bystanders including a Mr Wigmore who was known to the ship’s master, were ‘pressed’ into joining them to gain access to the schooner. Once aboard O’Connor and Bradley tied the men, secured what guns and ammunition the schooner carried and terrorized the master and his crew, threatening to shoot the master first at the least sign of resistance. They wanted their freedom and would stop at nothing to get it.

A sizeable crowd had gathered on the banks of the river and shots were exchanged but the convicts warded off capture by holding the pressed men as hostages.

On the 16 September an attempt to set sail failed when the schooner became stranded on the bar. The bushrangers ordered most of the cargo thrown overboard to lighten the ship. As the ship awaited the turn of the tide Wigmore and four others were sent back to shore. The boat that had taken them ashore was supposed to return for the other reluctant passengers but it did not come back. Finally the Sophia got underway for Port Phillip Bay. Three days later, after a stormy crossing, Bradley and O’Connor set foot at night on the sands of the bay that would later be named Bushrangers Bay.

Ashore at Cape Schanck

The morning after landfall the two convicts made their way inland. The two sailors pressed into rowing them ashore had somehow managed to give them the slip and had struck out across country.

During the 1850s much of Victoria was divided into pastoral runs, large areas of Crown land held by lease for grazing. The Barker brothers, John and Edward held the run, Barrabang (Cape Schanck). The station was about a mile from the small bay where the bushrangers had landed and when they arrived only two young station hands, Sam Sherlock and Robert Anderson, were ‘at home’. Anderson wrote his version of the encounter in letter to the Argus in 1908 in response to another published account of the event.

The story given by the two bushrangers was one of shipwreck; their vessel had foundered, there were just four survivors and the other two had become separated from them. The two station hands gave them a good breakfast. Anderson had noticed that each of the men had a gun and ‘under the long blue woollen shirts worn in those days, pistols in their belts’. After eating, the two men tried to empty their wet guns and pistols and ‘ran’ (cast) bullets. The light rifles belonging to the youths were in the corner of the kitchen and the convicts eyed them, asking if other people were around. Uneasy, Sherlock quickly replied that the overseer and six men were expected at any time – they having been out shooting bulls. The two visitors were given tobacco (and Anderson thought perhaps dry powder) before they left. They had thanked the two station hands for their hospitality and told them they could have the whale boat on the beach. Anderson added that they “seemed amused when told there was no fear of bushrangers until they got to the other side of Melbourne”. (The Argus, Melbourne, Saturday 27 June 1908.)

The whale boat was later brought up from the beach using block and tackle and carted by bullock dray to Henry Tuck’s home near Flinders. Two planks near the bow had been stove in. The idea was to repair it and put it to use as a fishing vessel but this was never done. Instead it became a roof on a pig sty at the Tuck property until it broke apart. Mrs Tuck also recalled meeting the bushrangers. She had been staying at a cottage near Boneo when the two came by, claiming to be shipwrecked sailors and asking to buy bread. She had given them a loaf but refused to take the shilling they had offered.

The two sailors who had managed to slip away from the bushrangers had passed by the Balcombe property, ‘Tichingorourke’ (later ‘The Briars’), near Mt. Martha and had given warning. Accordingly the workers had been armed. However Dame Mabel Brookes, grand-daughter of Alexander Balcombe and writer of several books, tells a slightly different story. Her grandfather at the time was away at the goldfields. Emma Balcombe, Alexander’s wife, on hearing the bushrangers approach had sent her young children under the house to hide. She and the cook had fed the men well, given them provisions and clothes, convinced them that they had no powder for their guns and pointed them on the road to Melbourne.

‘What have you shot me for?

The next reported stop was at the farm of John King near Brighton. King, his wife and other occupants of the house were overwhelmed and tied up. The two bushrangers ransacked the house before sending King’s son to the stable to get a saddle and take it to a paddock where Robert Howe was ploughing. The ploughman was told to unharness the horses to which he replied that he would be stopping soon for dinner and they could have them then. One of the two aimed his gun and fired, the bullet shattering Howe’s upper arm. It is reported that Howe exclaimed, “My God, what have you shot me for?” with the heartless response, “You’re one less!” (South Australian Register, Adelaide, Friday 7 October 1853). Howe’s arm was later amputated by Dr. Edward Barker, a tricky operation for the time but a successful one and Howe lived. On horseback the two made their way north.

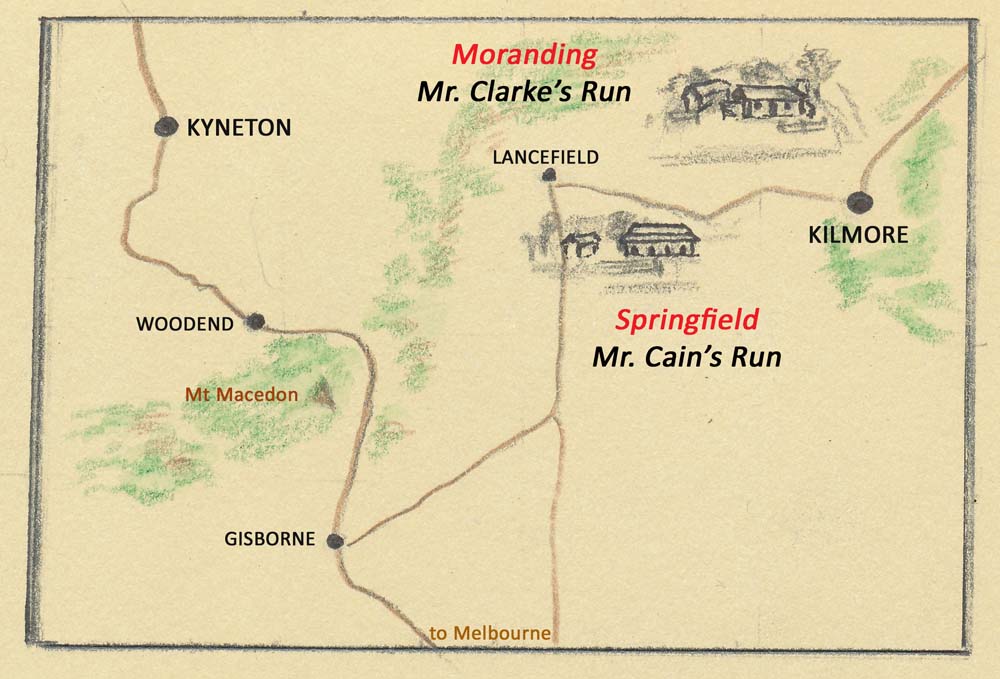

From here accounts of the movements of the two men differ. One version has the two bushrangers travelling by back roads towards the goldfields. Others say there were sightings at Prahran and they were seen crossing the bridge at Richmond. There was also a report of them robbing a party of diggers on the Sydney Road. The hue and cry and police pursuit that had begun in Van Diemen’s Land was continued in Victoria with a group of troopers sent to capture them. A reward of £200 (and a free pardon – if appropriate) had been offered for their capture. Sightings led the police towards Deep Creek, Gisborne, the Black Forest.

Further Blooodshed

Moranding, the large station of Mr John Clarke lay between Lancefield and Kilmore. Here Bradley and O’Connor abandoned their horses when they became bogged in a waterhole and continued on foot. A little further on was one of the station’s huts. Only the wife of the occupant was at home. They asked her for a meal which she prepared for them and they gave her a sovereign. While there they saw the manager of the station, Mr William Smith, going to the horse paddock. Approaching him they asked for a job, hut-keeping or shepherding.

On being told that the property was changing hands and they should speak to the new owner, Mr Flinn, they went to find him at the men’s hut. Smith went to his own house. Minutes later he heard barking and stepped outside to investigate. Both newcomers were there. O’Connor pressed a gun to Smith’s head while Bradley tied him up and tied his wife to him before leaving. She managed to free herself and release her husband who ran for his horse and rode the four miles into Kilmore for the police.

The bushrangers had gone towards the homestead where they bailed up the owner, Mr Clarke and his gardener. The two attempted to run for shelter but Bradley fired two shots at Clarke – one passing through his hat, the other through his whiskers – and O’Connor fired at the gardener, wounding him in the body.

By the time Smith arrived back from Kilmore with two police cadets, a trooper and a sergeant the convicts had left. A black tracker was sent for and he picked up their tracks heading towards the Tantaraboo Ranges.

Desperate Men

The bushrangers next appeared at Springfield, the run owned by Mr James Cain (also spelled Cairn or Kane in some reports). At the shepherd’s hut Bradley and O’Connor tied up the two shepherds and had the wife of one of the men prepare a meal. Here they also melted down a metal teapot to make bullets and made several holes in the wall through which they could fire should the police arrive. Later in the afternoon the ration carrier’s cart arrived and the bushrangers forced the driver to take them on to Cain’s homestead arriving before nightfall. Here they overcame and tied up eleven men.

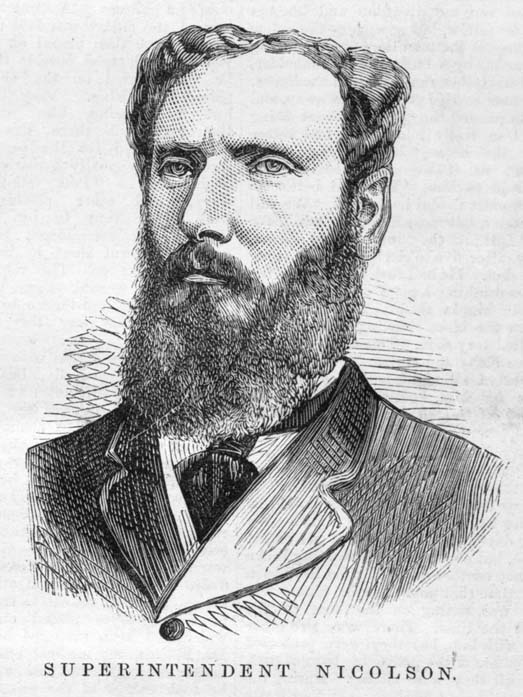

When the police arrived they found the bound men and learned the homestead was in the hands of the bushrangers. One report has it that Cadet Nicolson tried to enlist the aid of the station hands to help him arrest the bushrangers but most had been ticket-of-leave-men from Van Diemen’s Land and were not willing to become involved. As the men were being untied a figure approached on horseback. It was dusk, and thinking it was Mr McCulloch, the Police Inspector, Nicolson hailed him. However one of the station hands recognised him as one of the bushrangers. At that moment Cadet Thompson and Sergeant Ostler approached. Thomson was carrying his pistol and O’Connor called to him to put it down, firing as he spoke. The shot hit Thompson in the chest, passing through his lung.

[Thompson did not recover from his wound. He was sent to England for treatment by a leading army surgeon but he died three years later in Melbourne.]

Bradley appeared on foot, mounted one of the police horses at the urging of O’Connor and, after a further exchange of shots, the two disappeared into the bush. One report has it that the rest of the police horses had been scattered and the police were not able to give immediate chase.

Capture

At first light the chase was resumed and the police overtook the bushrangers. Details in various reports again differ as to their capture. In the version given by Cadet Nicholson in the Melbourne Supreme Court he stated: When we came up with them Bradley dismounted, getting behind a tree. I rode at O’Connor. We each fired. O’Connor’s ball whizzed past my cheek, slightly grazing it and I could not pull my horse around directly. He fired again and I returned his fire. This time his ball went through the neck of my horse. Sergeant Nolan then struck at O’Connor with his sword, but he parried the blow with his gun. O’Connor galloped off and we exchanged shots again. My revolver pistol missed fire [sic]. I had now come up to him and struck him on the head and knocked him off his horse. We had a struggle and at last I threw him down. He then said he would surrender and asked me not to shoot a fallen enemy. Just then Osler came up with the other prisoner. (The Melbourne Herald, 19 September 1853)

The two were taken to Kilmore. Later, under heavy escort, they were moved to Melbourne for trial.

Conviction and Execution

The trial of the two Pirate Bushrangers before Mr Justice Williams drew a great deal of interest.

Bradley’s behaviour in court was considered appalling. He was eating, he grinned and laughed as evidence was given and when the guilty verdict with its sentence of death was handed down he said “Thank you, my lord, I’m very glad of your sentence. I’m very glad indeed.” And he laughed.

Henry Bradley and Patrick O’Connor were hanged at 8.00 a.m. on 24 October, 1853 outside the Melbourne Goal in front of a large crowd of spectators, ‘lucky to be hanged in comparative comfort for the mob would have torn them apart in an attempt to lynch them’.

After the execution a phrenological examination was carried out on the skulls of the Pirate Bushrangers. The conclusion was that both men were natural born killers. Patrick O’Connor was destined to be a violent murderous man while Henry Bradley was a criminal idiot. (SBS ‘Conversation’ – see references)

An Act of Cowardice

At the end of September Captain Bawdy of the schooner Sophia had to face the Mayor of Melbourne under the Convict Prevention Act. Public feeling ran high against him for bringing the convicts to Victoria where they had caused so much mayhem. In the press he was called an ‘animal’ as ‘it would be an insult to humanity to denominate the fellow a man’. He was accused of cowardice (ten men against two convicts -surely they could have been overpowered?) and his conduct was seen as a ‘disgrace to the British navy’. However no further action was taken as he had not wilfully attempted to assist the convicts.

***

FORTY FRENZIED DAYS

- Wednesday September 14, 1853 PM. Absconded from places of employment near Circular Head. Raided several huts for firearms and supplies.

- Thursday, September 15, 1853 early AM. Alfred Phillips fatally shot. Mail carrier wounded. Forced way on board schooner Sophia. Hostages held.

- Friday, 16 September, 1853 AM. Attempted departure unsuccessful. Ship stuck on bar. 11 PM. Sophia sets sail for Port Phillip.

- Monday, 19 September, 1853 PM. Landed near Cape Schanck in whaleboat.

- Tuesday, 20 September, 1853 Daybreak. Cape Schanck. Barker’s station

- Wednesday 21 or Thursday 22 September, 1853. Mt. Martha. Balcombe’s station

- Friday, 23 September, 1853 Near Brighton. King’s place looted. Shot and severely wounded Robert Howe. Intense police search. Pair travel north. Reported sightings and further raids.

- Sunday, September 25, 1853 Black Forest area. Pursuit by Police Cadets Nicholson, Thompson and Trooper Ostler. Raided Clarke’s station near Kilmore. Clarke fired at. Gardener wounded.

- Monday, September 26, 1853 PM. Cain’s station. Cadet Thompson fatally shot.

- Tuesday, September 27, 1853 Captured.

- Tuesday, October 18, 1853 Trial by jury before Justice Williams. Sentenced

- Monday October 24, 1853 8AM. Public Hanging outside (Old) Melbourne Gaol

References: Newspaper reports:-

The Daily News – Perth – 21 Nov. 1896

Colonial Times – Hobart – 27 October 1853 repeat report from:-

Melbourne Herald, October 19, 1853

South Australian Gazette – 8 June, 1850

The Argus – Melbourne – 27 June 1908

Cornwall Chronicle, Launceston, – Wednesday 5 October 1853

Truth – Brisbane – “Casual Chronicles” 21 March; 28 March ; 4 April 1915,

The Men who Blazed the Track – Peninsula Pioneers’ Experiences reprinted from The Peninsula Post

Riders of Time by Mabel Brookes

Convict Records from Port Arthur

Internet: SBS Conversation – James Bradley (University of Melbourne) ‘Natural Born Killers –Brain Shape and the History of Phrenology’