By Ilma Hackett, Balnarring and District Historical Society

What was passing through their minds, those men and women who were being ferried ashore that October day in 1803? Boatload after boatload – some four hundred and sixty souls altogether, three hundred of whom were convicts. Behind them, anchored in deeper water, were the two ships (H.M.S. Calcutta and the Ocean) that had carried them from England. Ahead was unknown land. They stepped ashore on the beach of a small cove not far from today’s Sorrento.

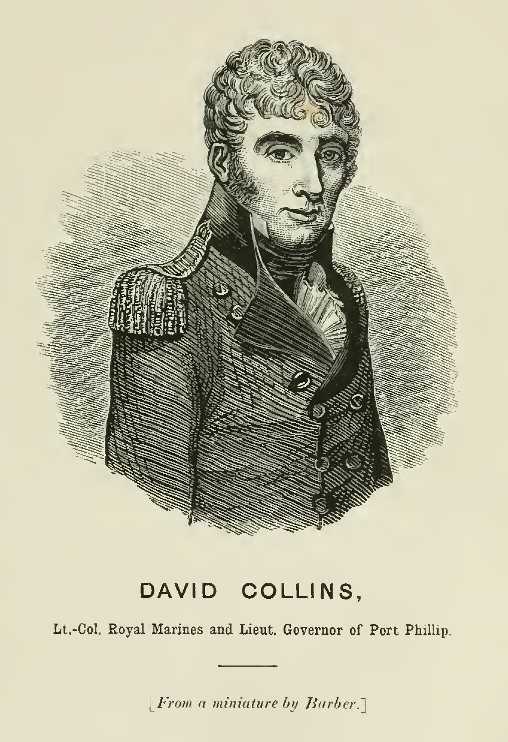

“Transportation” usually meant to the penal colony at Port Jackson on New South Wales’ east coast. This was a new destination. Swayed by the reports from voyages the previous year and the discovery of a new bay on the south coast, Lord Hobart, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, decided this might be a suitable alternative to Port Jackson. In fifteen years that colony had grown in size from the original 799 felons to over 8,000 – it was saturated – and authorities wanted to improve the moral tone by not dumping any more convicts there. In addition, a settlement somewhere in Bass Strait would prevent a foreign power (especially France) from controlling the strait or making a claim on the land. Such a settlement could also be a base for a sealing industry. Hobart commissioned Lieutenant-Colonel David Collins, as Deputy Lieutenant General of the new dependency under the Government of New South Wales. Thirteen official personnel would accompany him and fifty marines.

Lieutenant –Colonel David Collins R.N.

At 45 years of age Collins appeared to be the perfect person for the job. He had sailed with the First Fleet in 1788 and, as Judge Advocate and Governor’s Secretary, assisted Arthur Phillip in turning that tent city into an established community.

Born in 1756 David Collins joined the navy at the age of fourteen. He had served in the war against the American colonists who were fighting for independence from English rule. In Nova Scotia he had married Maria, daughter of Captain Charles Proctor and, after England’s defeat, they returned to England where Collins awaited another posting or some civil position. His father advised him to seek a place with the fleet that was soon to sail to Australia to establish a penal colony now that America was lost to the English government. He sailed with the Sirius in 1788. It would not be until 1797 that he returned to England. Collins enjoyed being back in ‘civilised’ England and his wife was certainly glad to have him home. But without a posting and on half pay, money was short. He spent time writing a book about the N.S.W settlement and life in Australia and was regarded as an authority on the subject.

H.M.S. Calcutta and the Ocean

The naval frigate, Calcutta, commanded by Captain Daniel Woodriff, was commissioned to transport the convicts to Australia. It had been refitted to carry the convicts in two between-deck prison rooms, an upper and a lower, where hammocks were slung for beds. For a convict ship the conditions were better than most. Living space was kept as clean as could be; provisions were adequate to ensure that as many as possible arrived in a healthy condition. Convicts were carefully selected and the ship’s surgeon was paid 10/- for each one who arrived fit for work. The ship was also commissioned to make the return trip with as much timber as it could bring. There was always the need in England for good timber for building new naval vessels.

The Ocean, a privately owned brig, captained by John Mertho, was chartered to accompany the Calcutta when it became obvious that the one ship was not big enough to carry everything and everyone. In order to make the round trip a profitable one for its owners, it had been engaged to continue on to China and bring back a cargo of tea. It was the store ship, laden with whatever was thought necessary for the new colony, plus the personal effects of the families aboard who were going as free settlers. Makeshift cabins accommodated the passengers. The officials were divided between the two ships, in cabin accommodation.

The two ships with their human cargo of convicts and free settlers eventually weighed anchor and left Plymouth on 24 April, 1803. The voyage took six months and after leaving Rio de Janeiro the two ships became separated. Mertho, following orders from Woodriff, sailed direct to Port Phillip while the Calcutta stopped at Cape Town to replenish supplies. The Ocean found the entrance to Port Phillip Bay first. The surf at the bay’s entrance appeared alarming but the ship was safely brought through the Heads and it dropped anchor in a wide bay. Two days later it was joined by the Calcutta.

The new colonists.

The arrivals were a mixed group of people. Roughly three-quarters were convicts transported to relieve England’s crowded prisons and hulks. A handful of these men were accompanied by their wives, self-exiled women prepared to chance all in an unknown place, hoping for a better life when their husbands had served their time and were again free men. In a few instances the families included children. Was this an adventure for them? The oldest convict was Robert Cooper, a man of 57; the youngest, two nine-year- old lads both named William. All three were transported for theft. The majority of the convicts were thieves; some were counterfeiters, fraudsters or embezzlers. A handful had been mutineers. Some were selected for the skills they could contribute: carpenter, sawyer, brick-maker, printer, shoemaker, brewer. Many were literate. Some were quite well-off, able to ‘buy’ a cabin on the ship and goods at the ports of call.

Fifty Royal Marines accompanied Collins to guard the convicts and protect the new colony. For them it was a military assignment. Collins had been proud of his marines at the outset. A few were accompanied by their wives. Single women had not been permitted to sail unless part of a family. Some marriages took place shortly before leaving England.

The free settlers numbered fifty-five, mostly men with their families looking for a more promising life. Ann Hobbs, the widow of a naval officer came with her son and four daughters, one of whom was married. They too had been chosen for what they could contribute to a new settlement. They had travelled on the smaller ship, bringing with them their possessions and items of use for their future life: tools, seeds and animals. One, John Hartley, included extra items that he intended to trade. The stores brought by the free settlers were additional to the Government stores. Some in fact had to be left behind in Plymouth as there was simply not enough room aboard the Ocean.

Then there were the civil officials: a chaplain and a surgeon for the colony. The surgeon had two assistants. The government also sent a mineralogist, a surveyor and a deputy commissary who was in charge of the provisions. The convicts were under the supervision of two superintendants and two overseers. Collins was without a Judge-Advocate but had been assured by Lord Hobart that one would arrive on the first ship to follow. A number of these officials were young men in their 20’s and two of the men had families with them.

Where to land?

Once inside the bay the travellers waited aboard for yet another week while search parties investigated the shores. First impressions were favourable. Surveyor George Harris wrote: “Its appearance is most truly delightful, covered with beautiful trees, shrubs and flowers”. Expectations must have been high.

The first parties ashore looked for water as an adequate supply of fresh water was essential for survival. The first drinking water was found by sinking double, perforated casks into the ground above the tide line where run-off water could be collected. Water, filtered as it passed from the outer cask to the inner barrel, was deemed drinkable although slightly brackish. Reports coming in from both the near and opposite shorelines of the bay were disappointing. There were no rivers, a few dry water courses and pools associated with swampland areas. There was a stream further towards the high peak now known as Arthurs Seat but no suitable landing place there. The reports also noted, disappointingly, that the soils were sandy and poor and there was a dearth of good trees for building purposes.

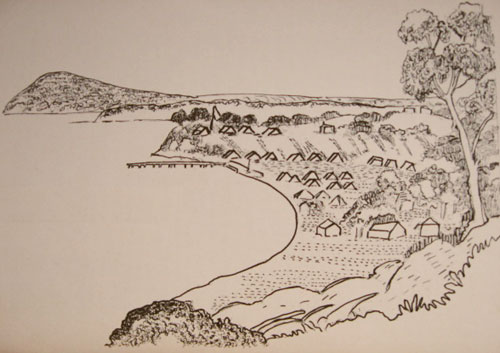

Collins decided not to wait any longer but selected the small bay adjacent to the ‘Watering Place’ as the site for the colony. He named it Sullivan Bay (after the British Under-Secretary of the Colonies). Preparations went ahead to unload both ships. On 14 October the livestock and stores were off-loaded. Goods were lowered into longboats and convicts, wading waist deep, hauled the boats the final distance through shallows to the shore. On 16 October all the convicts and marines were ashore and the free settlers landed on the following day. A tent village quickly appeared on and around the two headlands at either end of the bay and the five acres or so of land between the two. (The two headlands were later called the Eastern Sister and Western Sister.)

A Village springs up.

‘Home’ became one of the white, government-issue tents. These were grouped in orderly rows in segregated communities that made up the village.

At the back of the western headland were the hospital tents and those of the three surgeons. The convicts were housed behind the beach near the western rise next to an open area of parade ground. The tents for the marines and those of their officers were behind the parade ground. Closer to the beach and above high tide were the water-collecting casks and a copper used for communal cooking. They were not far from the public landing place. The supply tent and commissariat were further east with the magazine nearby. These were closely guarded, as was the water supply.

Collins’ marquee was set up on the eastern rise near that of the chaplain, the mineralogist and the surveyor. Not too far off was the tent of Hannah Power. Collins, parted from his wife for most of their married life, took a mistress. During this voyage his favour fell on the pretty young wife of convict Matthew Power and the liaison continued on land. Her husband benefitted from this arrangement. He went unshackled and received special privileges. This liaison scandalised some of the settlers and the newly married missionary, William Pascoe Crook, blamed the lack of moral tone of the settlement on the example set by Collins. Debaucher! Bigamist! Tongues wagged.

On the eastern promontory was the flagstaff; on the western one was a battery.

The free settlers were further inland. Each was allotted about five acres on which to establish a small farm. As the days stretched to weeks many replaced their tent homes with a timber hut.

Once ashore and allotted their own space the business of living began.

A marriage took place between convict Ron Garrett and Hannah Harvey in the colony’s early days. Hannah had arrived as his de facto wife. Ann, the wife of Sergeant Thorne, gave birth to a son, James William Hobart Thorne. The Lieutenant-Governor stood as one of his godparents when the baby was christened and the name ‘Hobart’ was his suggestion.

Collins regarded order and cleanliness as basic for a harmonious and healthy community to survive. One of the items among the stores was a printing press and Matthew Power, a printer convicted of counterfeit, prepared the Governor’s Orders for both the general community and the garrison. The first orders, printed on 16 October, set out the food allowance that each man, woman and child would be allocated. Until the colony could feed itself, the food needed to be rationed so the copy with its Royal Coat-of-Arms heading was displayed on a noticeboard for all to see:

To civil, military and free settlers – beef, 7 lbs; or pork, 4 lbs; biscuit, 7 lbs; flour, 1 lb; sugar, 6 ozs. To women two thirds; children above 5 years, half; and children under 5 years, one quarter of the above ration. Half a pint of spirits is allowed to the military daily.

The quietness of the small bay gave way to the ring of axes, saws and hammers and the sound of voices raised in command, conversation, complaint, or in song at the church services held on the parade ground on a Sunday by the Rev. Knopwood. The colony’s chaplain was a man who loved the good life. He mixed his religious duties with his other interests. Hunting was one of these and he spent time with the parties sent to shoot game to augment meat supplies. If the Sunday weather happened to be unfavourable he did not schedule a service. He also took on the role of magistrate for the settlement, settling minor arguments between the settlers.

Further Reports

The officials went on trips around the bay, observing and writing reports. Early reports held little promise: no water, poor soils, good timber trees scarce and the native people a threat. Two parties had been forced to fire on groups of Aborigines to stop them making off with items and native men had been killed.

At the end of three weeks Collins was convinced that this site was unsuitable for a permanent colony.

On 5 November he wrote to Governor King in Sydney requesting permission to transfer the settlement to Van Diemen’s Land to merge with the one being established there. The following day settler (and former navy master) William Collins left in a small cutter, with six convicts at the oars, to deliver the letter as neither ship was available. The convicts were offered a free pardon in return for undertaking the dangerous voyage. Lieutenant-Governor David Collins waited and those at Sullivan Bay continued their lives.

A convict’s lot

A number of the convicts were assigned as servants or labourers. The officers of the settlement were each allowed two, and others were assigned to the free settlers. Sergeant Thorne who was accompanied by his family, took one of convict lads, William Appleby, to live with his family.

Most of the convicts were divided into fixed work groups. Theirs was a life of labour. No horses had been brought to the colony and the convicts did the heavy work. They cleared tracks: one across the neck of land to the large bay of Western Port, another to the forested Arthurs Seat and a third led to the tip of the peninsula. The work parties on Arthurs Seat felled large trees and dragged the sawn timber back to camp on the heavy timber carriage. Convict gangs dug ditches or pits for latrines and sank wells in search of further water. They broke stones and erected whatever was required, such as a permanent store-house or huts. Work started on a substantial stone magazine. On the opposite side of the peninsula, about a mile away, a watch tower was erected. From there ships approaching the heads into Port Phillip Bay could be seen. Some of the convicts went out with fishing parties or hunting parties to bring in fresh supplies.

The convicts’ day started at 6.00 a.m. and work finished at 7.00 p.m., with breaks at mid-morning,mid-afternoon and a longer one at lunch-time. Curfew was imposed for nine o’clock at night.

Those men with specialised skills were given work that made use of their expertise. Thomas Rushton was able to make cloth from flax; Thomas Fitzgerald taught the colony’s children.

Any breach of discipline or sign of insubordination was punished by confinement, withholding provisions or the lash. Good behaviour might be rewarded with a measure of spirits and water.

Clothing was provided: trousers, breeches, waistcoat, two check shirts, hat and shoes. Sturdy footwear was needed for work but also made escape possible. Collins hesitated before issuing them.

Even though the settlement was so remote a number of escapes were attempted. Many believed that Sydney was just a few days’ walk away. Some even believed that China could be reached overland. Perhaps if one reached the coast it might be possible to be picked up by a ship. On 9 November six men absconded. Five were recaptured within the week. They were publicly flogged. Escape was pointless. Away from the settlement they faced death from exposure or starvation in unknown terrain, possibly murder by the natives. In the event that one should reach Sydney – 900 miles away – they would be punished and returned to face further punishment.

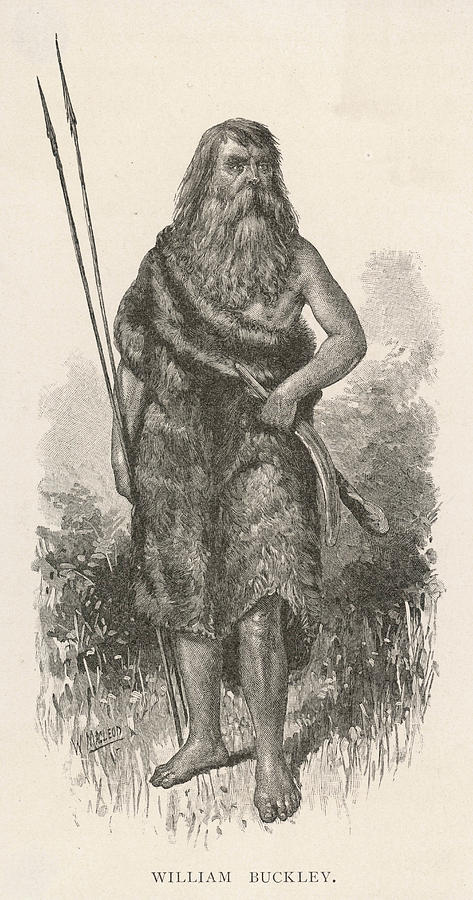

Another group of five escaped on the night of 27 December after having stolen food and other items. One was shot by a sentry but the others disappeared into the darkness..Three later turned back leaving William Buckley determined to go on alone. He later wrote, “The attempt was little short of madness . . .but life and liberty beckoned”. (The Life and Adventures of William Buckley p16) Twenty- seven convicts in all ‘went bush’ and twenty of these returned. Six died. Buckley miraculously survived and for the next 32 years lived with the Aboriginies, reappearing at the campsite of John Batman’s Port Phillip Association, in July 1835.

Convicts with families were given an area of land where they could build a hut and establish a garden but the privilege was withdrawn when it was abused. John Faulkiner (or Fawkner), his wife, daughter and son John Pascoe, were one convict family who did well. The boy, John Pascoe, would much later return to Port Phillip as a founder of Melbourne.

Attempting self -sufficiency

Few livestock had survived the sea voyage. Those that did were to be regarded as communal property to ensure a breeding program could take place. Two bulls, one cow, two heifers, twelve sheep, pigs, goats and poultry made up the complement of livestock. The lack of fresh meat plagued the settlement. Hunting for kangaroos was unsuccessful and only the occasional animal was shot. Rev. Knopwood was amazed by the size of the animal he killed, recording its various measurements in detail in his diary, beginning with its length from nose to tail as being 7’ 6” (almost 2.3 metres). The sight of kangaroos bounding across the open grass must have astonished the settlers. There was no animal like this ‘back home’. The birds too, were quite different: swans were black, other birds brilliantly coloured and one laughed raucously.

Native birds such as swans, ducks and pelicans were killed for food but Collins forbade the pilfering of nests for eggs and nestlings. Fishing in the waters of the bay yielded a variety of fish but not enough to feed over 400 people. Crayfish and other sea food were plentiful from the rock shelves on the other side of the narrow spit. However the sea could be treacherous and lives were lost.

The settlement spread out over about twelve acres and the countryside inland was pleasant enough.

The free settlers sowed seed brought from home in the gardens around their huts. They had more success than Collins; on his two acres none germinated from almost twenty varieties of seeds that were planted. The seed stock provided by the government was inferior. However Rev. Knopwood planted melons, onions and cucumbers and had fresh peas and beans to eat on New Year’s Day, along with duck.

Lieutenant Tuckey had reported that no spot within five miles would provide wheat or any other grain that required much moisture or good soil.

The weather was unlike anything the newcomers had ever experienced. In November it was unbearably hot. The temperature soared to 118 ° F (47 ° C) in the sun with winds from the north followed by a dramatic drop of temperature as winds changed direction. The tents provided some shelter but were stifling inside. Thunderstorms were frequent. February brought another heatwave and fear of fires.

The settlers were plagued by amazingly large and numerous flies that bit, and hordes of common flies. There were large ants whose bites were excruciatingly painful. Snakes were feared. An order was posted advising against swimming because of the voracious sharks and stingrays in the bay. There was much to loathe and fear.

A small graveyard was set aside for burials. Free settler, John Skelthorn died aboard the Ocean before coming ashore. ‘Baby’ Fletcher died soon after birth. His/her parents had lost another baby during the passage. Deaths mounted – accidents, illness, drownings. In all, nineteen people died.

The Marines

There was one marine for every six convicts. Collins needed a strong and disciplined garrison. The colony depended on it. Many were young and inexperienced although well trained. Their duties varied but as the weeks passed discipline became lax. Collins, himself a naval man, insisted on things being spic and span; huts were to be kept clean, uniforms neat and everything orderly. Inspections were held twice weekly. Slovenliness was not tolerated and was punished. The wives who had accompanied their soldier husbands were asked to do the washing for the garrison.

When not on duty there were few distractions to relieve boredom: no nearby town, no female company. Gambling was quashed. Each marine received a measure of spirits as part of their rations but many drank to excess. This led to the ration being watered down but even that wasn’t enough to prevent drunkenness. An order was issued: the ration had to be drunk at the point of distribution.

Many resented being called on parade so often. What was the point in this godforsaken place? Discipline was imposed and punishment meted out to offenders. In severe cases, as for the convicts, this meant a flogging. Insubordination meant a court martial. Early in January two trouble-making privates, Robert Andrew and James Ray, were flogged after a court martial that many saw as unfair. Collins worried about the possibility of rebellion.

At times the Aborigines seemed to pose a threat. The local Bunurong people were in large numbers on Arthurs Seat and, although the first meeting at the settlement had been quite friendly, ensuing encounters, especially between the exploring parties and other groups of natives, had not gone well. Stories of cannibalism spread. Mixed reports continued to come in from further afield. Hills on the other side of the peninsula had better soils and forests. An excellent river near the head of the Bay was found but a large group of natives had been belligerent and threatening. Surveyor Harris had written to his brother, “it was the most narrow escape that could possibly be and about 100 chances to one that I would have been grilled and eaten, instead of writing at this time”. As well as guarding the convicts, the marines were expected to guard against the ‘savages’. Collins reported that should he transfer the colony to the banks of the large river he would need a much bigger garrison for protection. Meanwhile, closer to camp, the fires of the Bunurong on Arthur’s Seat reminded the settlers of their continual presence.

Abandonment

Eventually Collins received approval from Governor King to move the settlement south. In December 1803 work on a jetty to facilitate the loading of the ships started immediately and did not pause even for Sunday’s church services.

War had broken out again between England and France and the Calcutta had left from Port Jackson for England. However the Lady Nelson arrived on 21 January 1804 to assist with the evacuation. The Ocean, having called into Sydney en route to China, was engaged by the NSW Government to make the trip to Van Diemen’s Land and it returned to Sullivan Bay. The settlement was dismantled.

At the end of January the ships set sail with the first group of people and stores headed for the Derwent River. It would not be until 20 May that the Ocean returned to take aboard the livestock and those who had waited behind. No-one stayed despite orders to Collins to leave a token number.

Sullivan Bay was abandoned. Did any of those departing look back as the ships pulled away?

References:

Voyage to Port Phillip Bay 1803 by Barbara Angell

No Place for a Colony by Richard Cotter

Victoria’s First Official Settlement. Sullivans Bay, Port Phillip by P.F.J. Coutts

The Life and adventures of William Buckley by Tim Flannery

from the internet: Australian Dictionary of Biography – David Collins

Historical records of Port Phillip by John Shillinglaw (Order books of Lt-Gov. Collins 1803 -4; The Journal of Rev. Rbt. Knopwood 1803-4)

The Collins Settlement Nepean Historical Society

Footnote:

The Collins Settlement Historic Site is between Sorrento and Blairgowrie. It is open to the public. A number of the relics from the site are in the Sorrento Museum which is open at weekends from 1.30 pm – 4.30 p.m.