It was one hundred years ago, on the evening of 31 October 1923, when a squad of constables at Russell Street police headquarters refused to go on duty. The move would result in the famous 1923 Victorian police strike. Looting and rioting would break out on Melbourne’s streets, and the death of two police officers in Frankston, by the hand of one of their own, would be narrowly averted.

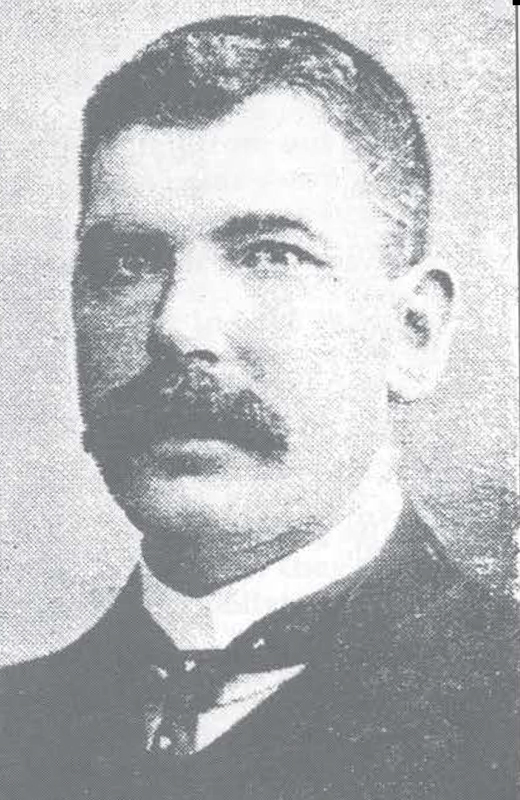

The first man out. Constable William Thomas Brooks led the police out on strike on 31 October 1923.

Out on strike

The police association of the time had made repeated efforts to improve the lot of Victoria’s police. They were considered understaffed and underpaid in comparison to their colleagues in other states. There was no pension system in place, and many police officers were struggling as pre-war standards of living had not returned, five years after the end of the Great War.

Things were tense among the force, but the tinder was ignited when the relatively new chief commissioner of police, Alexander Nicholson, set up a system of four “special supervisors” to secretly monitor beat cops as they went about their duties.

The police “spies”, referred to as “spooks” by rank-and-file members, were a step too far for many police and on the evening of 31 October 1923, Constable William Thomas Brooks led a small group of men out on strike. The trickle became a flood and before the government knew it, a third of the police force was on strike.

Most of the strikers were constables. Many were returned servicemen. Senior officers and detectives did not participate in the strike.

After 24 hours, the Premier, Harry Lawson, demanded a return to work and promised no victimisation, although there was no promise to meet the strikers’ demands. After 48 hours, the Premier again demanded a return to work but with no guarantees regarding victimisation.

Failing to get police back on the beat by the deadline, the decision was made to discharge 634 policemen; about a third of the Victorian Police Force.

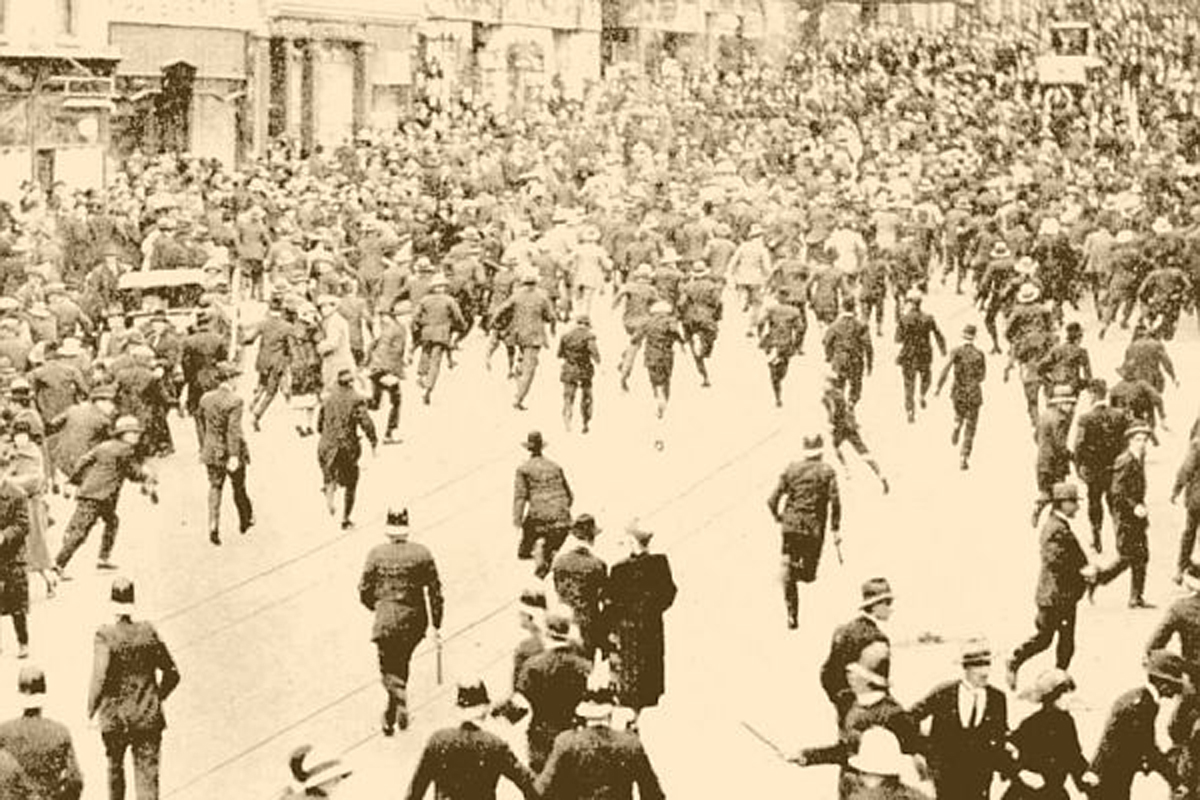

Special Constables charge the crowd during riots and looting that occurred while the police were on strike.

Riots and looting

Any belief that the dismissal of such a large number of police would have no ill effect was quickly dispelled when, on Friday and Saturday nights, looting and rioting broke out across the city. The mayhem resulted in three deaths, a tram being overturned, windows smashed, and merchandise being stolen out of stores.

Premier Lawson made a plea to the Federal Government for troops to prevent and put down trouble. It was refused. Over the weekend, five thousand volunteer “special constables” were sworn in to help restore order. They were under the direction of Sir John Monash at the Melbourne Town Hall and led by AIF veterans and Citizen Military Forces (CMF) officers.

The Premier of Victoria, Harry Lawson.

Reaction to strike

The strike was widely discussed including in the pages of the local newspaper of the day, the Frankston and Somerville Standard.

The first mention was a letter to the editor on 9 November:

Sir, There are several serious aspects of the situation in regard to the present police strike which are inclined to be overlooked by the public.

Having in my profession encountered numerous policemen and representatives of numerous professions and trades, I say, without fear of contradiction, that the fine work of the great majority of the members of the force compel admiration.

Physically, they are the finest body of men in the State, while their intelligence is generally keen and penetrating. The incidents of the strike have been terrible, but he would be an illiberal man who would suggest that the members of the force who went on strike were responsible for it.

The strikers have justifiable grievances, and the obnoxious “spooks” merit removal. The failure of the Government to soothe the discontent of the members of the force by granting reforms, has, to my mind, been responsible to an extent for the outbreak of unleashed larrikinism.

The Government, of which I am a supporter, could have used more tact in the handling of the situation, but, alas, the sagacity of a few members of the Ministry has been limited, with the inevitable consequences of a state of chaos.

Australia’s a free country, and everyone, whatever calling he may follow, should be entitled to receive consideration for his claims of redress.

The Government should receive the strikers back into the force without qualms, for the majority of them have served their country well during the war and in the maintenance of peace at home.

The following Friday, an article appearing in the same newspaper under the authorship of “The Knut” was far less conciliatory:

Any argument calculated to uphold the action of the ex-police in deciding upon strike measures as a means of attaining their ends cannot carry one ounce of weight in the minds of the people.

Any, and every argument so advanced, be it painted ever so flowery, must fail miserably when put to the Ministry, with a view to having these strikers reinstated.

Grievances, without a doubt, were being borne by the force, and that being so, the men and other measures which could have been adopted to rectify things, but, like so many sheep, they were led to their doom by a decoy of the worst type: the agitator.

The police force is looked upon as an intelligent and capable arm of the law, and we suppose, possessed also of much reasoning power, therefore, when trouble arises it is their bounden duty to do their utmost to reason things out; to pacify, and if possible, heal a wound, so to speak.

To place the mild term of strike to the recent acts of lawlessness, would be far too good, for at best the whole deplorable outburst was in reality, a rebellion, pure and simple, engineered by heretics.

As for the local shire, they too gave little sympathy to the strikers. A telegram regarding the strike, sent by the Lorad Mayor of Melbourne, was tabled at the monthly meeting of the shire councillors with all those present ‘heartily supporting the Government in the stand taken to suppress the police strike.

Frankston in the 1920’s. This day, locals were out celebrating a visit to the town by General Birdwood.

A Saturday night to remember

It was Saturday night on the 17 November 1923. Frankston police officers Senior-Constable James Culhane and Constable James Alexander Graham were on duty and charged with keeping order in the town.

Senior-Constable Culhane was well-known in Frankston. He had been stationed in the town for a little over a year having been transferred from the St Kilda Road depot. He had joined the force in 1897, was 47-years-old, and was married with three children. He was often mentioned in the newspapers of the day, appearing in court prosecuting various malfeasances, or attending to the policing business of the small but bustling township of Frankston. He possessed the distinction of being honoured by the Royal Humane Society for rescuing a man from the snow at Harrietville in 1910.

Constable Graham was a mounted constable at Frankston. He was a returned soldier and served abroad in the 17th Infantry Brigade. He had been serving in the police force for four and a half years and was also married.

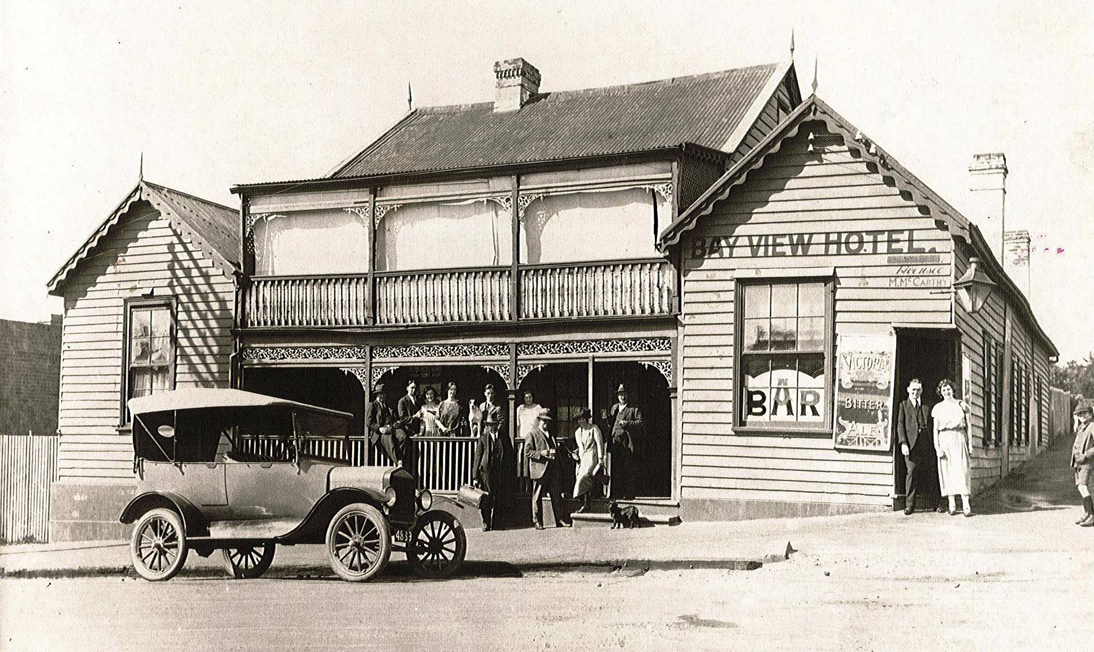

The Prince of Wales Hotel, Frankston.

The two police recounted that at about 11pm, they first came across Peter Gordon Hannah at the Prince of Wales Hotel in Frankston “under the influence of alcohol”.

Ex-constable Hannah had been discharged from the police force recently, as a result of going out on strike. He was 38 years of age and became a policeman in 1909.

After serving for some time as a mounted constable, he was transferred to the dismounted arm. He had been stationed at Brighton, where he was well known and often appeared in the newspapers of the day for various happenings around the area. He was married with five children.

Hannah was known to the two Frankston police officers, and was on friendly terms with them, but not on this night.

Hannah greeted the men cordially. “Good night” said Culhane, to which Hannah replied, “Good night, Jim” and they shook hands. He then greeted Graham and asked why he wasn’t on strike. Graham replied, “It’s too late to go out now.” To which Hannah said, “It’s not too late – come out, and be a man.”

Hannah handed both officers a pamphlet and the officers left the hotel and went over to the verandah of the Pier Hotel.

Hannah came out of the Prince of Wales Hotel, and walked to a motor car, and while the driver appeared to try and persuade him into the vehicle, his efforts were unsuccessful.

When the two officers made their way to the Bay View Hotel, Hannah decided to follow them and spoke to them again about the strike.

Culhane walked out of the hotel, with Graham following. At that point, he heard a struggle.

James Culhane circa 1911.

Going back in, Senior-Constable Culhane saw Constable Graham on his back on the floor. The striking police officer, Hannah, was kneeling over him with his thumb pressed into Graham’s neck. Culhane remonstrated with him, saying “it would do his case no good.” But Hannah was not to be talked down, replying to Culhane “You go to ––––. This is only a scab. I’m going to kill him.”

Culhane managed to get Hannah off Graham, with the striking officer then turning his rage on Culhane. Graham, now off the floor, came to Culhane’s assistance and they got Hannah back under control.

Despite both being attacked by Hannah, the two officers took pity on one of their own and tried once more to get him into Allan Johnston’s car and on his way home. Johnston agreed, but the agitated Hannah ended up damaging the car and the driver thought the better of it and drove away.

Culhane stated that this is where their patience ran out after Hannah had assumed a “fighting attitude”.

“We arrested him and took him to the watch-house, the accused struggling all the way,” said Culhane.

Inside the police station gates Hannah said he would go quietly, and was taken to the office. Culhane opened the door and went inside, and led Hannah in, between the two officers.

The Bay View Hotel, Frankston.

Shots fired

“Just as I was lighting the gas I heard a shot, saw a flash, and heard Graham fall,” said Culhane.

“I asked Graham if he was hurt, he did not answer, and then, as I was stooping over Graham, I heard another shot, and felt a stinging pain.”

Culhane had been shot in the back by Hannah, with the bullet lodging in his neck.

Culhane fell out of the office, and crawling around the side, leant against the wall. Hannah walked past Culhane and said, “Do you want another, Jim?” to which Culhane replied “No,’ I’ve had enough,” and Hannah made his escape.

Culhane’s wife rushed in with a candle to help her wounded husband. Culhane knew he needed medical help fast and began to crawl towards Dr. Maxwell’s surgery.

Graham, thinking himself seriously injured, staggered across the road to the Bay View Hotel, and seeking assistance discovered he had escaped with only a grazed collar-bone. He attributed his good fortune to the fact that the overcoat which he was wearing at the time of the incident was thickly padded on the shoulder, thereby preventing the bullet from penetrating.

Chelsea railway station, where Nicholson worked as a porter.

A busy night for a young lad

Saturday 17 November started early for Neil Nicholson. A porter at Chelsea railway station, he rose at 4.30am in order to go on duty at 6am; starting early in order that he might finish at 1pm so that he could travel to Northcote to see his mother.

He did so, and, returning at night, tired out with his long day, he fell asleep on the train and was carried on to Frankston. Little did he know that the shooting had occurred and there was action aplenty with all hands searching for the escaped shooter who was feared to have fled north.

Nicholson discovered three other passengers had also missed their stops, so organised a car to return them to Carrum.

Once they reached “Chelsea House”, the young porter ran inside to grab some money to pay his fare.

The Chelsea police had been telephoned, and were on the look out for suspicious activity. No sooner did Nicholson come out than a local sleuth, who had meantime arrested the car and occupants on suspicion, told him to “step in”.

This he did, and without a word was whirled off to Frankston.

Not a word was said. Nicholson was conjuring up visions of being tried for murder, sedition and a hundred dreadful things.

They journeyed around Frankston and district until the small hours of the morning until suspicion of their involvement waned and they were told they could go home.

On the way back they were detained for a second time by search parties of police. Lights were flashed in their faces and the Frankston and Somerville Standard reported that “our hero cracked hardy, but felt a little shaky.”

After a close scrutiny one of the police recognised the lad porter from Chelsea, and as their innocence absolutely established, they proceeded on their way, finally making it home.

The newspaper reported that “since then Neil has been the hero of the hour at Chelsea. All the girls look in him as a kind of modern Sir Galahad. Lucky Neil!”

“Quite an exciting time”, he told the newspaper. “I rose in the morning at 4.30am little dreaming of the exciting day before me. I arrived back at ‘Chelsea House’ tired, but thrilled, at 4.30am, exactly 24 hours later. I am too tired for words”.

The location of Hannah’s capture. The Mordialloc Bridge pictured in the early 1900’s. Picture: State Library of Victoria.

Battle to save Culhane

Meanhile at about 12.30 on the morning of 18 November, Mrs Culhane put a call out to Dr Maxwell for help telling him she believed two police officers had been shot and injured.

“In consequence of what I was told, I went to the Bay View Hotel, and saw Graham,” said Dr Maxwell.

“From what he told me I went to the police station, from thence to my surgery, where I saw Culhane staggering up the path. I assisted him in and examined him. I found he was shot, and seriously injured.”

Dr Maxwell took him in a cab to a private hospital, where he further examined him, and found a wound above the left shoulder blade, bleeding freely.

Culhane was X-rayed on Monday 19 November and the bullet located. An operation was performed on Tuesday by Drs Maxwell and Le Soeuf, and the bullet extracted. It was reported that, after the operation, Culhane was “progressing very favorably”.

Two weeks later, the Frankston and Somerville Standard reported “Senior Constable Culhane’s many friends will be pleased to learn that he has left the Hospital” on Tuesday 4 December, just in time to give evidence at the case against Hannah, but that it would be some time before he could resume policing duties.

While recovering, Senior-Constable Wilson, of Woomelang, was brought in to take temporary charge of Frankston police station.

Hannah captured

After the shooting, word spread quickly, and search parties set out to capture the absconded Hannah.

At about 4am on 18 November, Constable T. Nicholls of Mordialloc saw a car approaching Mordialloc Bridge and intercepted it.

“What is your name?” the constable asked of the occupant.

“What is that to do with you?” came the reply.

“I am a constable of police, stationed at Mordialloc, and I am looking for an ex-constable named Hannah, who is said to have shot two Frankston police,” said Nicholls.

“Are you Hannah?”

Not ready to give up yet, Hannah replied “No, my name is Brown.”

Nicholls pushed the occupant by asking his profession.

“A labourer, out of employment,” said Hannah.

“Were you ever in the police force?” asked Nicholls.

“No,” said Hannah, denying he had been at Frankston that night.

Nicholls asked him about the mark above his eye to which Hannah replied “I was in a brawl at Chelsea.”

Nicholls’ suspicions were aroused, and he took the suspect back to the police station. He telephoned Frankston, and Detective Sergeant Armstrong and Constable Ryan headed to Mordialloc station where they identified him as ex-Constable Hannah.

He was searched, and a revolver was found in his possession containing three live cartridges and two empty shells. Detective Sergeant Armstrong informed the accused, in answer to his question, that he would be charged with shooting Culhane and Graham with intent to murder.

He was taken to MeIbourne by Detective Sergeant Armstrong and remanded at the city watch house.

Hannah appears in court

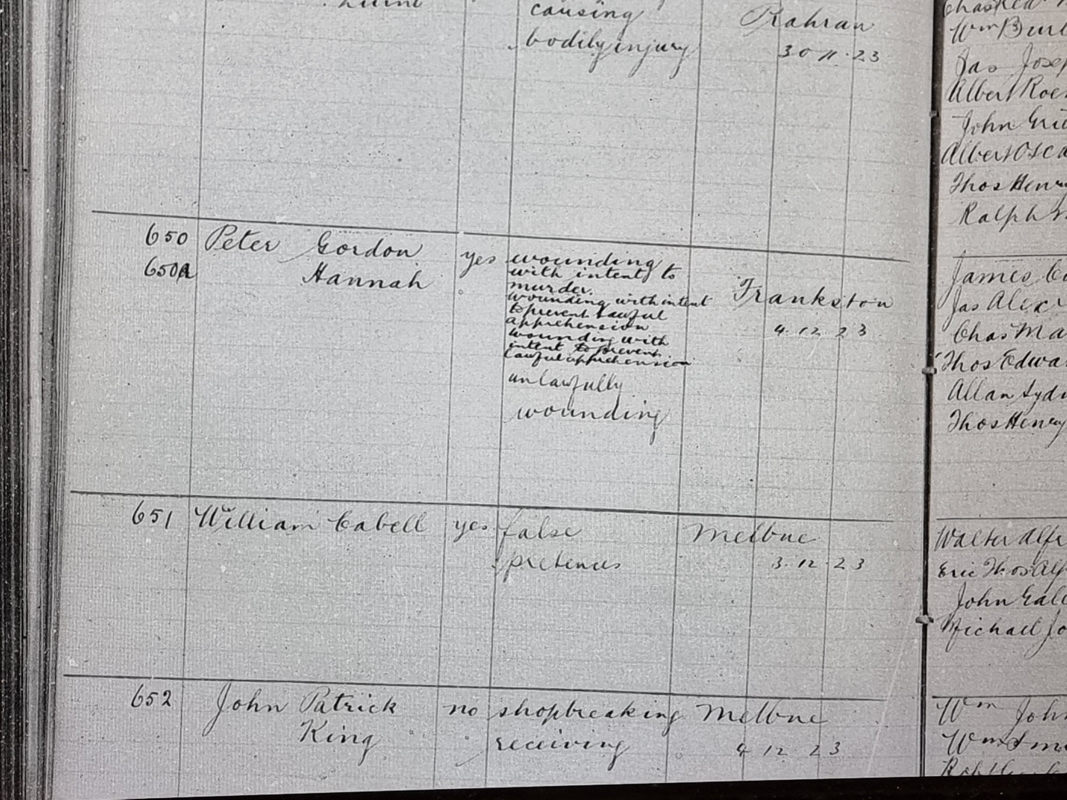

Hannah appeared, on Tuesday 20 November, before Messrs. Armstrong (chairman) Oates, and Brown, Justices of the Peace, on remand from the City Court, and was charged with having, on 18 November, shot with intent to murder Senior-Constable James Culhane, and Constable James Alexander Graham.

In outlining the case, Sub-Inspector Spratling detailed the happenings from the time accused was seen in the Prince of Wales Hotel, up to the time the shooting took place, and called witnesses to the stand.

“I was in uniform, and was wearing the overcoat and clothes produced, which showed bullet holes. I have known the accused for some time, and was friendly with him,” said Culhane.

Graham stated when he heard the shot, he felt a stinging pain in his shoulder.

“I fell to the floor,” said Graham.

“I got up and went onto the path and saw Culhane leaning against the wall. I then went into the street and ran to the Bay View Hotel. While there someone opened my shirt, and a bullet fell out.”

After more testimony from the driver, Allan Johnston, and the officer that arrested Hannah, the Crown closed its case. Hannah, who pleaded not guilty, reserved his defence, and was committed to appear at the Criminal Sessions on 10 December.

The trial

The Criminal Court was crowded on 14 December 1923, when Hannah, a tall and powerfully built man, was presented before Justice Macfarlan and a jury on charges of having wounded Senior-Constable Culhane, with intent to murder him, at Frankston, on November 18, and of having wounded Culhane with intent to prevent his arrest.

Hannah denied the charges.

In a statement from the dock, Hannah said he had been a policeman for 14 years. He had a wife and five children dependent upon him. He was one of the strikers and had been through a very difficult time. His wife, he said, had tried to scrape together sufficient money to undergo a serious operation. This worried him terribly, and he took to drink. He did not remember going to Frankston that night, nor did he remember meeting Culhane.

He remembered meeting Graham and having a scuffle.

“I think the man with whom I had the scuffle was Graham,” said Hannah.

“I can also remember having received a heavy blow. Despite what has happened, I think the constables will agree when I say they are my friends. I am not in the habit of drinking.”

“Only the fact that I had a wife and family dependent on me made me take to drink. I had no intention of wounding the constables.”

“This man’s career has been hopelessly blighted,” said Mr Eugene Gorman, appealing for clemency on behalf of Hannah.

Mr Gorman declared that Hannah, who had gone on strike, had been a member of the police force for 14 years, during which time he had acquitted himself well. Hannah had a wife and family.

He had been presented on three counts, and the jury had formed the opinion that he did not fire at Culhane with intent to murder or harm him in any way.

Hannah’s actions had been affected, to an extraordinary degree, by drink.

Hannah was found guilty of having unlawfully wounded Senior-Constable Culhane at Frankston and was remanded for sentencing.

The court records from Hannah’s trial.

Hannah sentenced

Before Justice Macfarlan in the Criminal Court Peter Gordon Hannah, who had been found guilty of having unlawfully wounded Senior-Constable Culhane at Frankston on November 17, was arraigned for sentence.

Mr Justice Macfarlan dryly remarked that Hannah was fortunate in not being found guilty on a more serious charge; if the outcome had been different for Culhane and Graham, the outcome would have been very differrent for Hannah.

Justice Macfarlan, however, could not disregard the finding of the jury, which apparently thought that the prisoner did not shoot with intent to murder or with intent to wound.

At the same time it was impossible to shut one’s eyes to the fact that it was a most serious offence.

He would take into consideration the fact that the prisoner was undoubtedly drunk at the time.

The maximum statutory sentence prescribed was three years’ imprisonment, and in the circumstances it would not be right to impose a sentence of less than two years’ imprisonment with hard labour. That was the sentence sentence Hannah would have to undergo.

Released early

In the meantime, the police strike had been resolved with the police getting many of their demands met, and an election held.

The new Labor government, headed by George Prendergast, was considered much more sympathetic to the police officer’s cause and Hannah’s case came to the attention of the State Attorney General, William Slater.

Slater made the decision to release Hannah after just nine months of his two year sentence. He explained the release came on the recommendation of Mr Akeroyd, Inspector General of Prisons, who had reported that Hannah’s conduct jn prison had been exemplary, and that he had no criminal instincts.

Slater further said that Hannah’s wife was in delicate health, and that she has five young children to support. Slater had been assured that Hannah, if released, would be given a position at £5/5/ a week. He had, therefore, been released on £100 bond to be of good behaviour.

Hannah’s release was not popular in all circles with one newspaper, The Australasian, writing an article scathing of the Prendergast government’s decision in September 1924:

No sooner is it well in office than it releases a criminal who, had he been more prosperous in his criminal effort, would probably have been hanged.

Presumably be is now eligible for reinstatement in the police force when Mr. Prendergast can safely fulfil his promise to “reinstate every man who was dismissed.”

What of the future?

It appears it wasn’t long before Senior-Constable Culhane transferred way from Frankston, with the Frankston and Somerville Standard reporting in March 1925 that “Mrs. Culhane, wife of Senior-Constable Culhane, erstwhile a most popular and zealous officer of Frankston, paid a visit here yesterday, and renewed several old friendships. We are pleased to state that Senior-Constable Culhane is enjoying the best of health at North Melbourne, where he is stationed.”

By 1934 Superintendent James Culhane had been appointed as officer in charge of the C.I.B., succeeding Superintendent Walsh when he retired.

It was reported that for five years, Superintendent Culhane oversaw the Midland district, with headquarters at Maryborough. Then he was transferred to take charge of the South-Eastern district, including Gippsland, with headquarters at Malvern, where he had “remained up to the present time”.

The last mention of James Culhane was in October 1945 when he was listed as a pall-bearer for the funeral of a retired police officer.

Things may not have been as smooth for Hannah. It appears he had a number of further brushes with the law.

In August 1930, when Hannah was unable to pay two outstanding electricity accounts, the Electricity Commissioner disconnected the electric light and sealed the fuse box only for it to be discovered, in September, that the lights were still on in the Hannah household. This led to a charge of fraudulently reconnecting the supply, with a fine of £5 , in default imprisonment for one month.

Another brush with the law came in May 1931, when he pleaded not guilty to a charge of having stolen a quantity of firewood, the property of Joel Carter, from the police paddock at Dandenong.

In that case, the jury found Hannah not guilty.

Acknowledgement: The above story has been taken from various newspaper accounts of the incident.