By Peter McCullough

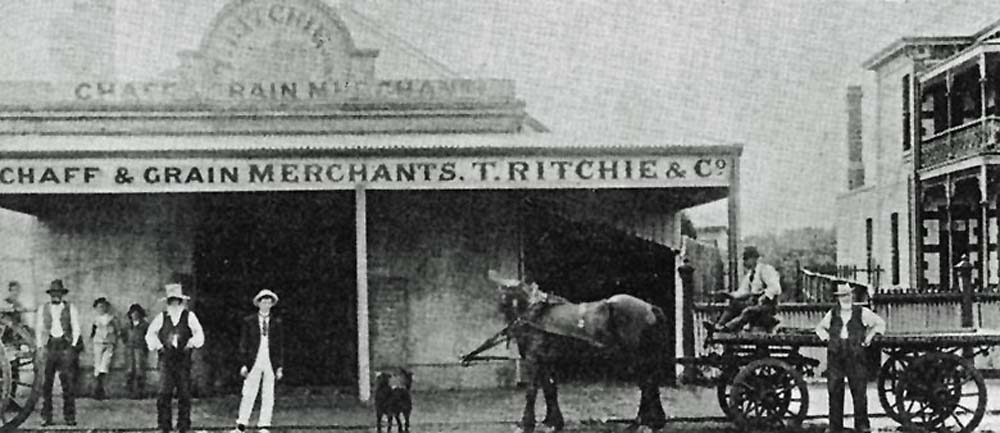

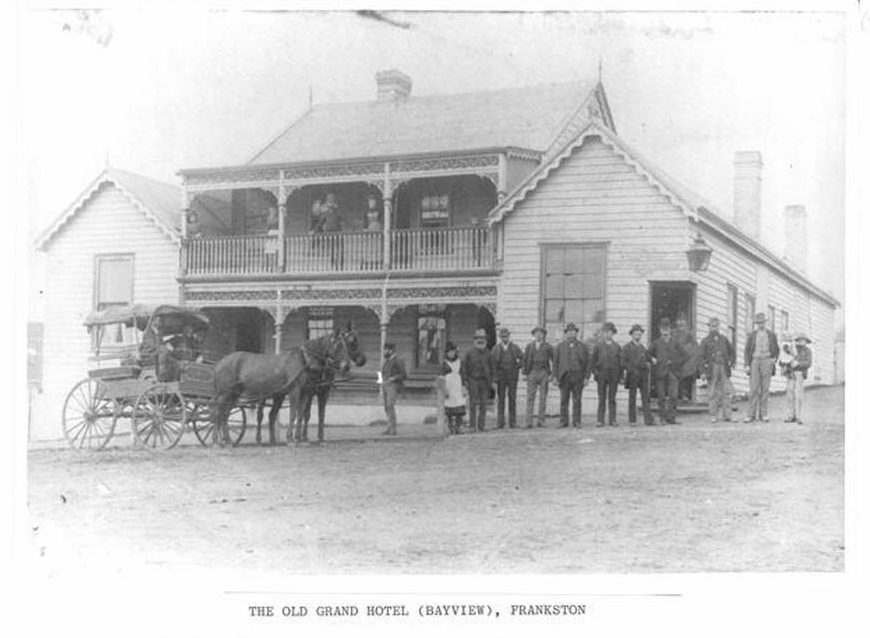

“I come from a race, Mr. Ritchie, who take no insults from any man, even if they should come to the gallows for it,” was the response Henry Howard gave to Thomas Ritchie, storekeeper, after the latter had commented “I hope you have not done anything that you will be sorry for.” Ritchie was one of those nearby businessmen who had been summoned to the Frankston Hotel on the evening of the 14 August, 1875 when Henry Howard stabbed Elizabeth Wright, the licensee, to death in the hotel dining room. For good measure, he also stabbed the barman, Thomas Harman. By the time Ritchie arrived at the hotel, Harman was lying dead on the pavement. Howard’s comment proved prophetic: for his actions he went to the gallows.

Mornington

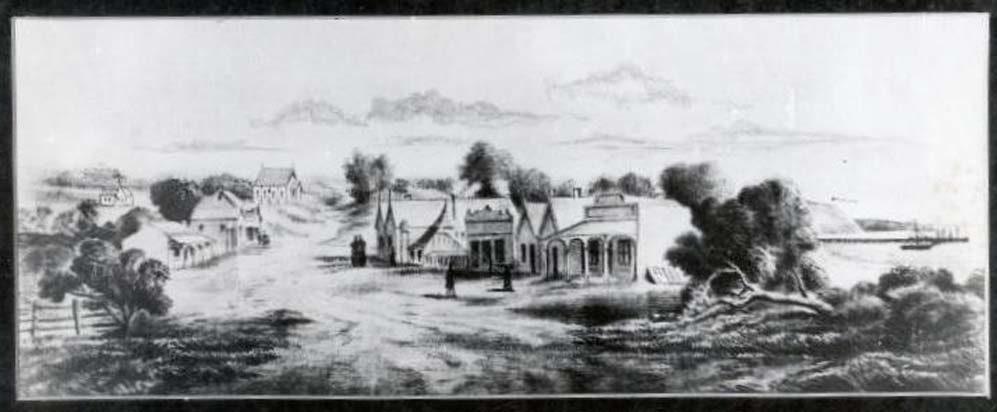

While the Tanti was the first licensed hotel in the township of Mornington, being shown on a map prepared in 1854, the “Schnapper Point Hotel”on the Esplanade and the “Mornington Hotel”on the corner of Avenue Road (now Wilsons Road) and Brewery Road (now Nunns Road) were the next premises in Mornington to be licensed. Both hotels appear on a map dated November, 1858.

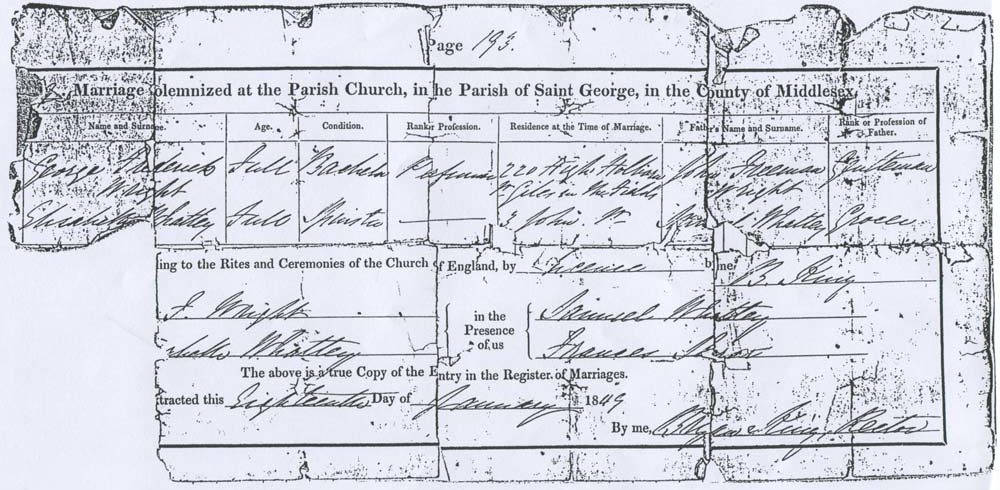

On 29 April, 1857 Henry Howard was awarded the licence to the Schnapper Point Hotel, but patronage dropped off when he installed a mistress (Mrs. Wright) while his wife and children were still in residence. This resulted in the licence passing to T. Rennison in 1860, and the hotel was referred to as “Rennisons” before it became the “Royal Hotel” in 1876.

The original licensee of the Mornington Hotel was Harley Goodall who had built a brewery beside his establishment. On 17 March, 1858 The Argus advertised first class accommodation at Mornington House with Harley Goodall as proprietor. Taking advantage of the newly-built pier, the advertisement referred to the availability of a steamer from Melbourne once a week. Goodall soon became licensee and the title of hotel was adopted.

The original licensee of the Mornington Hotel was Harley Goodall who had built a brewery beside his establishment. On 17 March, 1858 The Argus advertised first class accommodation at Mornington House with Harley Goodall as proprietor. Taking advantage of the newly-built pier, the advertisement referred to the availability of a steamer from Melbourne once a week. Goodall soon became licensee and the title of hotel was adopted.

In 1865 Harley Goodall, who had been experiencing ill health, travelled to England with his wife and family where he died aged 46.

However Goodall’s departure provided Henry Howard with the opportunity to resume his role as a publican as the Rates Book of 1865 records a Mr. Howard as ratee for a hotel and 18 acres, and in 1866-67 a 12 room house which would correspond to the specifications of the original Goodall property.

During February, 1865, Henry Howard advertised in The Argus first class accommodation for families and gentlemen at the Mornington Hotel at Schnapper Point. A fishing boat was available for the use of visitors and advertisements referred to both steamer and coach access from Melbourne. While Howard had become the licensee, Mrs Goodall, who had returned to Australia with the children, apparently lived on the property and participated in the day-to-day running of the hotel. Meanwhile Howard found that public pressure was sufficient to move Mrs Wright to Frankston where, in 1866, he installed her as licensee of the Frankston Hotel. It goes without saying that a certain amount of pressure would also have been exerted by the unbelievably tolerant Mrs. Howard!

In December, 1867 Henry Howard applied to transfer the name and licence of the Mornington Hotel to a new location in Main Street: “I, HENRY HOWARD, the holder of a publican’s licence for the house and premises known as the Mornington Hotel, situated at Mornington, do hereby give notice that it is my intention to APPLY to the justices, sitting at the Petty Sessions to be holden at Mornington on Saturday, December 21, to REMOVE the LICENCE and SIGN to a house now rented by me, containing two sitting rooms and two bedrooms, lately occupied by Mr. Cahill, bootmaker, and situated in Main Street, Mornington.” (The Argus, 11 December, 1867.)

In 1868 the licence of the Mornington Hotel was transferred to the new premises in Main Street. The original Mornington Hotel, established by Harley Goodall, was advertised for sale in The Argus and in May 1868 it was purchased by distinguished academic Professor William Parkinson Wilson who renamed the property “Wolfdene”.Since then it has been a private residence except for a short period (1877-1881) when the Backhouse brothers conducted the Mornington Grammar School on the site.

By 1877 the licensee of the Mornington Hotel was Cornelius Crowley who changed the name to the “Cricketers Arms”; the name “Mornington Hotel” lapsed. In 1889 Crowley commissioned prominent architect William Pitt to build the “Grand Coffee Palace” next door. In 1892 he transferred the licence from the Cricketers Arms to what became the “Grand Hotel”.

The Frankston Hotel

Accordingly, in 1866 Mrs Wright became the licensee of the Frankston Hotel, a role that she would fill until her death nine years later. She was described as a widow and was accompanied by her three year old son, Frank, a consequence of her association with Howard. Liquor licensing records show that, while the previous licensee, Henry Simpson, had transferred the licence to the Frankston Hotel to Mrs. Wright in 1866, he subsequently transferred the licence for the hotel on the other side of the street, also known as the Frankston Hotel, to Henry Howard. While his wife retained the licence for the hotel in Mornington, where she lived with their four children, within a short time Howard had moved into his Frankston establishment; although records are hazy, it would seem that, instead of trading as competitors, Mrs. Wright and he formed a business partnership and by 1875 they co-owned the two Frankston Hotels.

By 1875, however, the partnership was under stress, apparently due to the fact that Mrs. Wright was drinking to excess. This perception would appear to be supported by Dr. Dimock’s witness statement at the subsequent trial when he stated “…the deceased had been a very heavy drinker, and had suffered from delirium tremens.” (The Argus, 21 September, 1875. Page 7.)

After repeated disagreements, Howard offered Mrs. Wright 100 pounds to give up her share in the business so that it could be sold. She refused the offer and Howard continued with his plans to sell. Fearful, Mrs Wright engaged Thomas Harman to mind the bar, but also protect her and look after her interests until the property was sold. Howard disapproved of this situation, even believing that Mrs. Wright and Thomas Harman were in some sort of relationship. A week before the murder Howard said to Mrs. Wright that he would hang for her; that it would be “ war to the knife, and the knife to the hilt.”

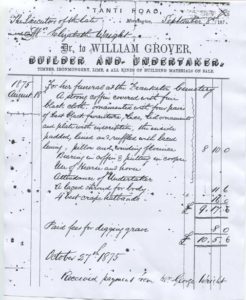

The sale took place on Friday 13 August, 1875 to Mark Young, a publican from Emerald Hill. Mrs. Wright, Howard and Harman remained in the hotel although the greater portion of the furniture and effects had been cleared out by the purchaser. On the Saturday evening, after dinner, an agitated Howard stabbed Mrs. Wright in the presence of their 12 year old son. Hearing screams, Harman, who was serving in the bar, rushed to the dining room where he confronted Howard. He, too, was stabbed whereupon he staggered back through the bar and collapsed on the pavement.

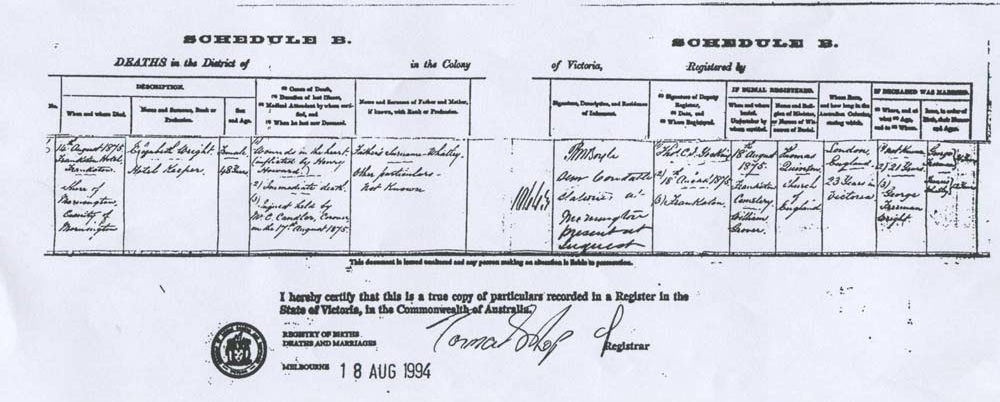

The Inquest

This was conducted on Tuesday 17 August and, as the reporter for The Argus stated “As all parties are well known for miles around, there was a great deal of interest taken in the proceedings…which lasted from 10 in the morning to half past 9 o’clock at night.

First to appear was Jane Harman, widow of Thomas, who told of the mounting tension between Mrs. Wright and Henry Howard. Mrs Harman was followed by a number of other witnesses including 12 year old Frank Wright; Frederick William Storer who was delightfully described as the hotel’s “generally useful man”; William Davey, the publican at the nearby Bayview Hotel; Thomas Ritchie, storekeeper; Richard Boyle, senior police constable from Mornington; and James Neild and George Dimock, medical practitioners.

At the conclusion the jury foreman announced the verdict: “…pre-meditated murder on the part of the prisoner.” The prisoner was then formally committed by the Coroner for trial.

The Trial

This took place before Mr. Justice Molesworth at the Central Criminal Court on Monday 20 September, 1875. Henry Howard “…was indicted for having wilfully and deliberately and with malice aforethought murdered one Elizabeth Wright at the Frankston Hotel, Frankston, on the night of 14 August last.” Howard pleaded not guilty. The various witnesses who had appeared at the inquest were required to repeat their testimony.

While the Crown expressed the opinion that the evidence was sufficient to conclude that the prisoner was guilty as charged, the counsel for Henry Howard urged the jury to find him guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter, “…in which case he could get as high a sentence as 15 years penal servitude. He pointed out that the prisoner must have been sincerely and devotedly attached to Mrs Wright, when he had deserted his own wife and family to live with her. It had also been proved that he treated her with kindness, and showed the utmost solicitude for her when ill.” (The Argus, Tuesday 21 September, 1875. Page 7.)

The plea by the counsel for the defence notwithstanding, the jury returned after 10 minutes of deliberation with the verdict: “Guilty of wilful murder.”

Mr Justice Molesworth then completed proceedings with his summary: “Prisoner at the bar, you seem in several ways to have lived a very bad life, both as regards your relation to this unfortunate woman whilst you had a wife and children living, and then on the termination of that intercourse by your being the cause of her sudden and violent death. At the same time you caused the sudden and violent death of a man whom you had associated in some way or another with her. In the eyes of any rational man there does not appear to be any ground for such suspicions as you probably entertained; but whether you were right or wrong, nothing of that kind could form the slightest excuse for the terrible crime you have committed. You seem to have performed this crime in a fearless and dauntless manner, plainly accepting the consequence. No doubt you could have found some more secret way of carrying out your intention, but you acted openly in defiance of the laws of God and man. I hope the spirit you have shown up to this time , the language of pride rising above all fear of consequences, will not continue, for your fate in this world is, I must tell you, hopeless. I trust sincerely between this and the time of your death you will be enabled to make your peace with God, and be brought to view your conduct in a proper light, to feel it must bring down upon you the universal condemnation of your fellow creatures and probably the condemnation of your God if you do not sincerely repent.” His Honour then passed the sentence according to the usual formula. (The Argus, Tuesday 21 September, 1875. Page 7.)

Being convicted, the second charge against Henry Howard of murdering Thomas Harman, was not proceeded with.

The Execution

The Leader carried a detailed and graphic description of the execution of Henry Howard which took place at the Melbourne Gaol on Monday 4 October, 1875. Readers were informed that: “The Rev. Lorenzo Moore, whose endeavours, since the passing of sentence, to bring the prisoner to a sense of guilt, have been attended with very satisfactory results, was engaged with Howard in prayer from nine o’clock up till the time of execution.”

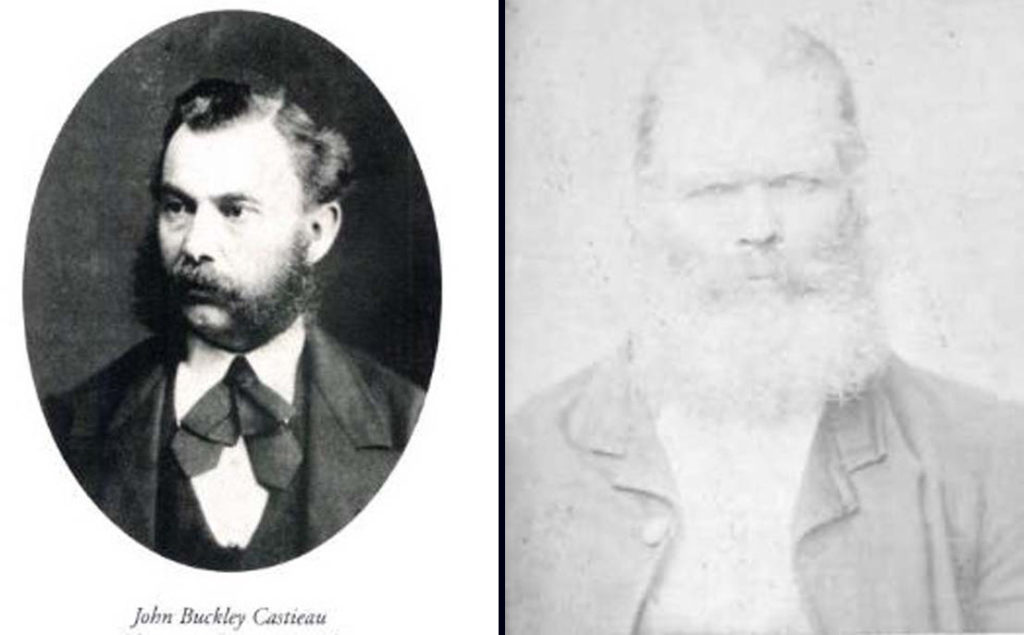

At the scaffold the governor of the gaol, Mr. Castieau reminded Howard that the time had arrived for him to make any confession which he might have in contemplation. “ ‘All I wish to say,’ he said, ‘is that I am guilty of the murder of the woman Wright.’ After a slight pause, he proceeded to say he had wished to plead guilty to the murder, but his friends had persuaded him not to do so. …He was quite satisfied with the trial and the sentence, he said, and desired to thank the gaol officials for the kind treatment he had received at their hands since his confinement. As regarded Harman, he felt convinced that he never intended to kill him. ‘I shall die a repenting Christian,” he continued, and raising his head to permit the executioner to bare his neck, he ceased speaking. Gateley (the hangman) performed the remainder of his task with great alacrity…” (The Leader, Saturday 9 October, 1875. Page 12.)

REFERENCES.

The Argus. Monday 16 August, 1875 (News of the murders);Wednesday 18 August (Inquest); Tuesday 21 September, 1875 (Trial).

The Leader. Saturday 9 October, 1875 (Execution).

Cullen, Joy. “The Wolfdene Story.” Mornington & District Historical Society, 2016.

Moorhead, Leslie. “Mornington-In the Wake of Flinders.” Stockland Press, 1971.

Wright, Clare. “Beyond the Ladies Lounge-Australia’s Female Publicans.” Text Publishing, 2003.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

For assistance in searching out old photographs my thanks to Val Wilson and Joy Cullen from the Mornington and District Historical Society and Val Latimer from the Mornington Peninsula Family History Society.