Book review by Peter McCullough

Australia’s contribution in World War One is well known: from a population of less than 5 million, an astounding number exceeding 400,000 would enlist. Of these, some 60,000 would not return.

However, as Peter Monteath points out in “Captured Lives”, Australia itself could not remain untouched by war and had to consider how to deal with the ‘enemy at home’- people whose nationality was that of one of the states with which Australia was locked in battle.

At first that meant Germans, but over time it meant many others including people from Austria-Hungary, Turkey, and Bulgaria. The rate of arrest and detention of people who provoked the suspicion of the authorities, or even their neighbours, grew in the second year of the war. It peaked in May, 1915, when the casualty lists from Gallipoli were being published. Many of those interned because of the suspicions levelled against them were bewildered by their treatment. Their frustration was compounded by the harsh reality that they had no idea when the war might end and when they might be released.

Of nearly 7,000 people who were interned in Australia during the First World War, the only genuine combatants captured as a result of a military operation were the survivors of SMS Emden which was sunk by HMAS Sydney. The others were housed initially in camps in each state although, as the war continued, there was a consolidation at one large camp at Holdsworthy in NSW for economic reasons.

In Victoria, the police depot on St Kilda Road and the artillery barracks at Maribyrnong housed the first prisoners, but it was clear that neither of those facilities would suffice in the longer term. The military authorities decided to establish a camp at Langwarrin on the site of a former military camp, the land for which had been set aside in 1886. At that time McClelland Drive was known as Camp Road and the camp’s existence had led to the establishment of a railway station nearby.

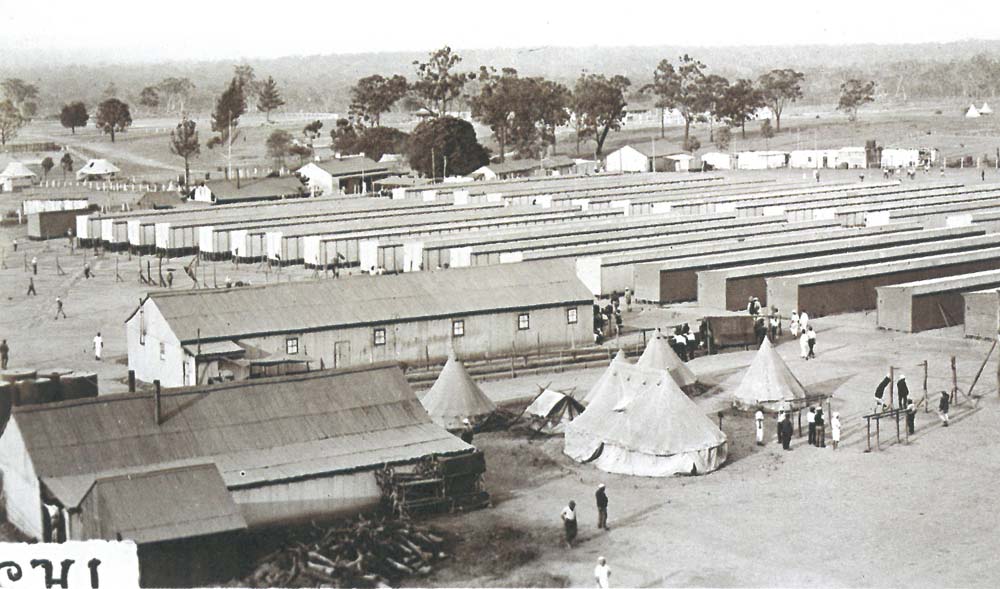

Although it was intended that Langwarrin would house up to 500 internees, in November 1915 it was recorded that there were 769 Germans, 104 Austrians and 72 Turks in the camp. Accommodation was at best crude. Over time, the prisoners supplemented the leaky tents with wooden structures, built largely by the sweat of their own labour and at their own expense. However the photograph taken towards the end of 1915 indicated that conditions were greatly improved.

“In time, Langwarrin was closed down and its population transferred to New South Wales. Yet Langwarrin had a longer history than most camps. It served as a kind of transit camp for internees from other military districts who were being sent on to the camps further north. In at least one instance, the conditions offered men in transit fell far short of acceptable standards. Prisoners on their way from Western Australia were placed in arrest cells in Langwarrin where they shared facilities with Australian soldiers undergoing treatment for venereal diseases.” (Page 43) By December, 1917, only 320 detainees remained at Langwarrin.

Today the site of the former military/internment camp is the popular Flora and Fauna Reserve.

While conditions in the camps established during the Second World War were of a reasonable standard, the same could not be said about the earlier camps, particularly Holdsworthy which at one time held over 6,000 prisoners. Peter Monteath manages to capture this quite graphically:

“With so many men gathered together in one place and with little to occupy them, Holdsworthy was not just spartan but could also be rough. Some criminal elements in the camp banded together in 1915 to form a group called the ‘Black Hand’. They resorted to mafia-like strategies of extortion and bashings to exert their influence; other prisoners came to fear for their lives. Eventually some of the crew from the Emden countered the threat by forming the self-styled ‘White Hand’. On 6 May, 1916, its members saw to it that the driving elements behind the ‘Black Hand’ were ‘herded together, overpowered, beaten up, and eventually thrown over the barbed wire’. As these dramatic events unfolded, the military authorities looked on.” (Page 51)

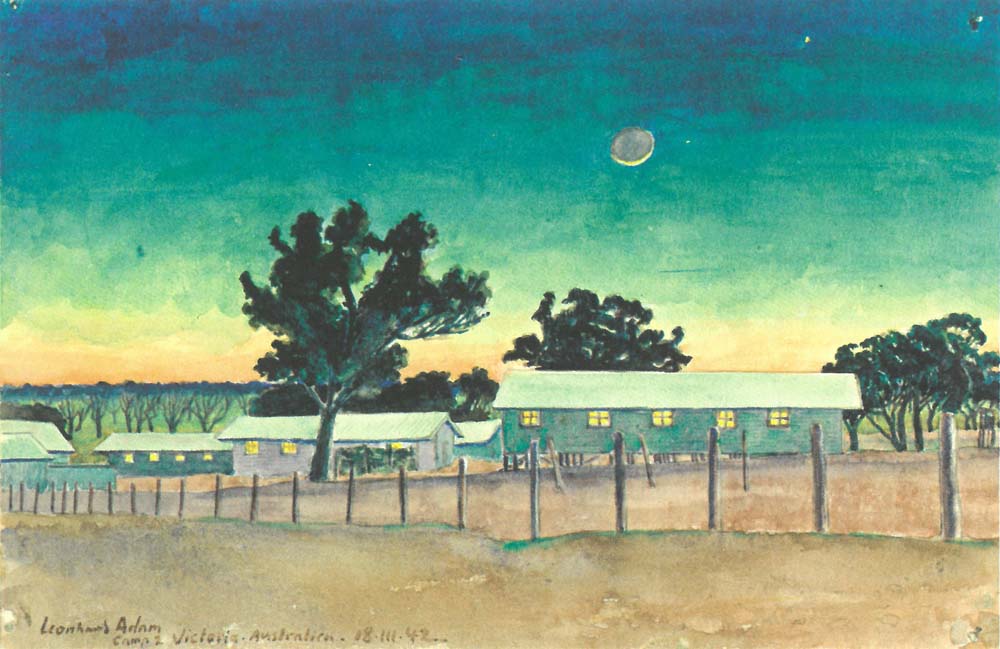

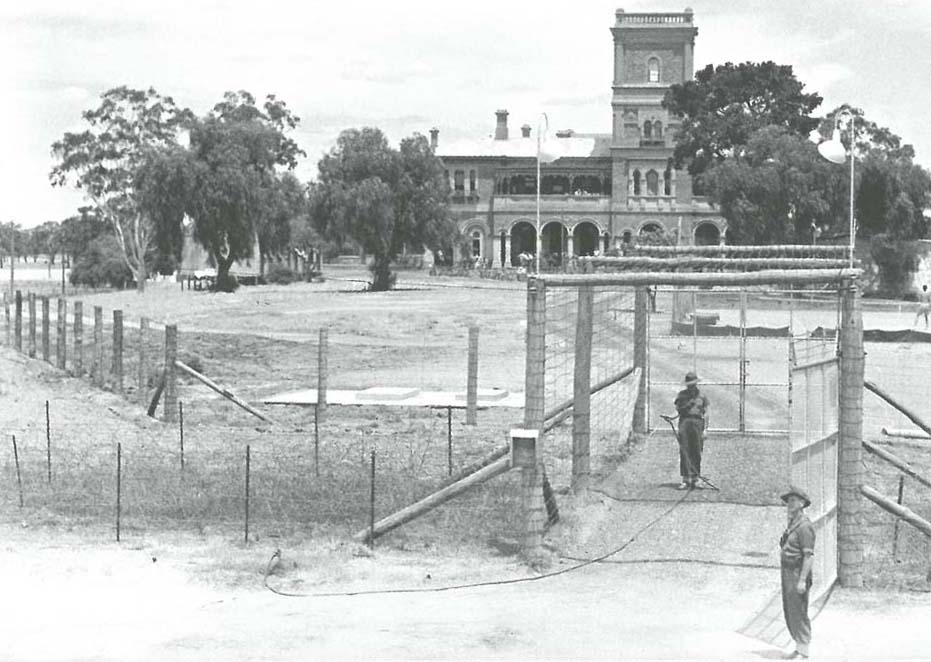

During the Second World War one of the many tasks that the authorities faced was housing the thousands of prisoners of war as well as a large number of internees whose background and/or nationality made them a security risk. Consequently a number of special camps were established, staffed mainly by World War One veterans who were considered too old for front-line duty. In Victoria these camps were located in the Goulburn Valley (Tatura, Rushworth, Murchison and Dhurringile) and Myrtleford.

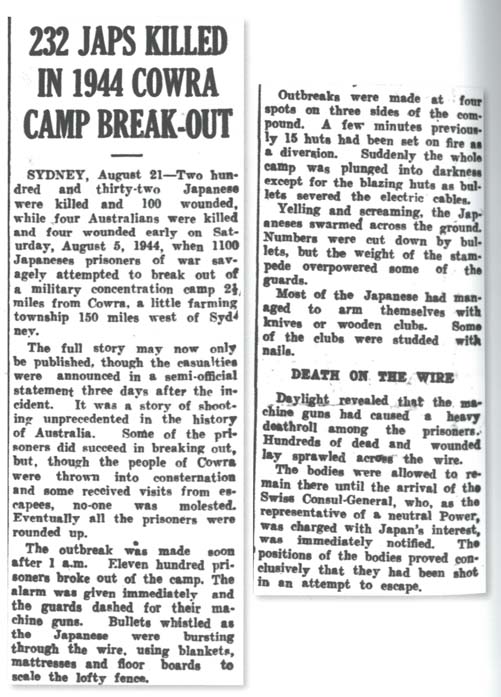

“Captured Lives” provides information about the camps and the challenges they presented. The Cowra breakout, which resulted in the death of 232 Japanese prisoners and 4 Australian soldiers, is dealt with in some detail, as is the treatment of the ‘Dunera boys’, a shipload of internees, most of whom had fled Nazi Germany and were predominately Jewish. They had been treated harshly by the British authorities and their guards on the ship had been quite brutal. Fearing more of the same, they were herded onto a train bound for Hay. However, as one passenger recalled: “Once we were on the train everyone was friendly, especially the guards… Our guard, George, got tired of standing beside the door with his rifle and came to sit beside us to have what he called a ‘yarn’… ‘Just hold my rifle for a sec. while I roll myself a smoke.’ We were quite flabbergasted…” (Page 130).

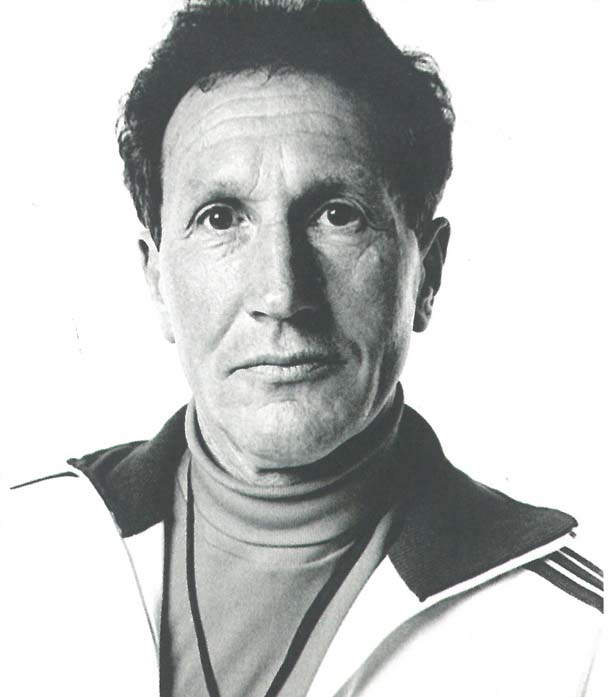

Monteath’s book contains a number of short pen pictures of some of the camps’ occupants. Two, in particular, are colourful identities: Theodor Detmers, the captain of the German merchant raider the Kormoran which sank HMAS Sydney, and who later led an escape of 17 German officers from Dhurringile; and Franz Stamfl, a Dunera boy who rose to prominence as an athletics coach, initially in Britain where Roger Bannister was one of his proteges, and later in Australia.

CAPTURED LIVES – Australia’s Wartime Internment Camps by Peter Monteath is available at all good bookshops. RRP $40.