By Peter McCullough

THIS is the title of one of a number of books written about the unsolved murders which occurred at Wonnangatta Station in Victoria’s high country in January, 1918. The mystery has close links to the Mornington Peninsula, and Hastings in particular.

Who was Jim Barclay?

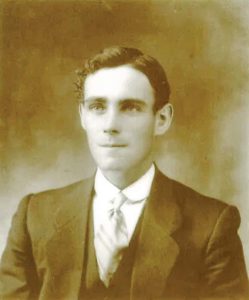

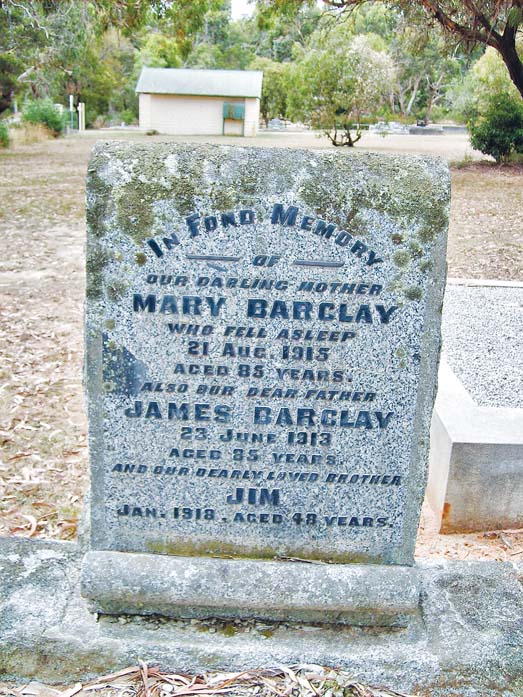

James Barclay (or “Jim” as he was better known) was born in Hastings on 18 February 1869. He was the fourth child of James and Mary Barclay who had come to Hastings in 1860: he had an older brother (John) and sisters (Jean and “Tossie”), and a younger sister (Molly).

James Barclay senior, an immigrant from Scotland, had owned a fishing vessel named Hero and when he purchased land in Barclay Crescent, Hastings, in 1880 he built the family home and named it Heroville. The house was only demolished in 1996.

Jim Barclay attended school in Hastings and had regular encounters with authority for fighting and a minor case of arson in which the police were involved. Religion played a large part in the family life of the Barclays and was apparently a cause of friction between the devout James senior and his son.

In 1883 Jim left school with a “certificate of a child being sufficiently educated” and worked at Heroville until 1886 when he departed to seek his fortune on the goldfields. Most of the next decade was spent around Mansfield although by 1897 Jim had moved from gold-prospecting to rural tasks such as sheep shearing and contract work such as post splitting. Ten years later he had leased land in the Howqua valley and trading in cattle had become an important part of his life. Jim was highly regarded in

the area for his skills as a bushman.

In 1910 life changed for Jim Barclay when he married 19-year-old Lizzie Cantieni who had been living with Jim’s neighbours in Howqua, the Fry family. The civil ceremony held on 23 December was not attended by any member of the Barclay family, possibly due to the fact that Lizzie was seven months pregnant at the time; in fact his family did not find out about the marriage for some years.

Lizzie gave birth to a son on 22 February 1911 in Mansfield; christened James he was always known as “young Jim.” The joys of marriage and parenthood were to be short-lived for the couple as Lizzie died of a form of tuberculosis on 18 September, 1911.

Jim Barclay was a tall man, with a strong physique and a reputation for his skill with horses and cattle. Burdened with a baby and no family within hundreds of miles, he turned to the friends he had made in Mansfield and they, in turn, gave him support and assistance. But by 1914 young Jim had been sent to live with his aunt Molly and her husband (Jack Campbell) at Vermont.

In 1912 Jim Barclay first visited the Wonnangatta valley when he called on the Bryce family in his capacity as a cattle trader. Meanwhile, Jim did contract work for Arthur Phillips, the owner of Glenroy Station near Mansfield. When Phillips became the joint owner of Wonnangatta Station he sought out a capable manager: Jim Barclay was considered the ideal choice for the job because of his industry knowledge, his association with the area, and Arthur Phillips’ trust in his skills and judgement.

So in April, 1915 Jim Barclay became manager of Wonnangatta station.

Where is Wonnangatta Station?

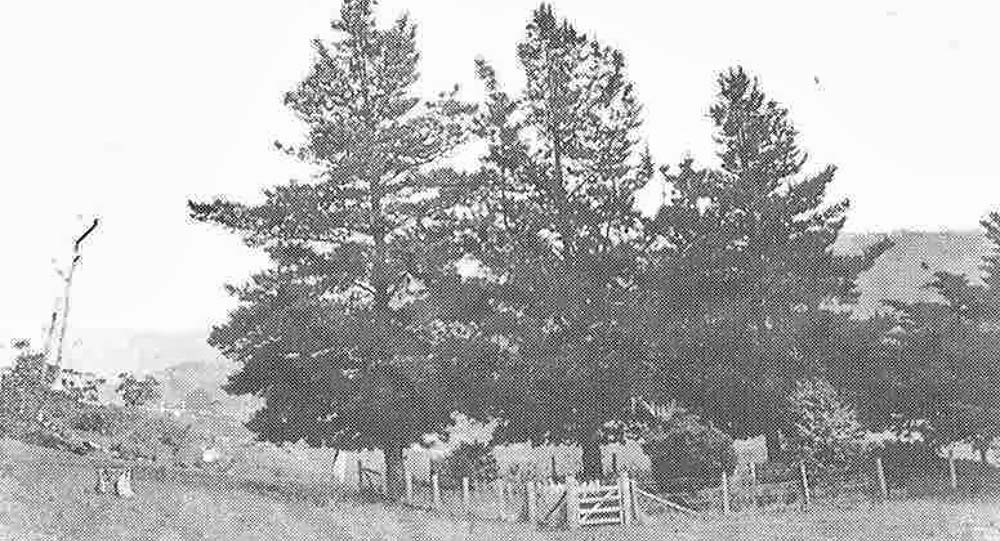

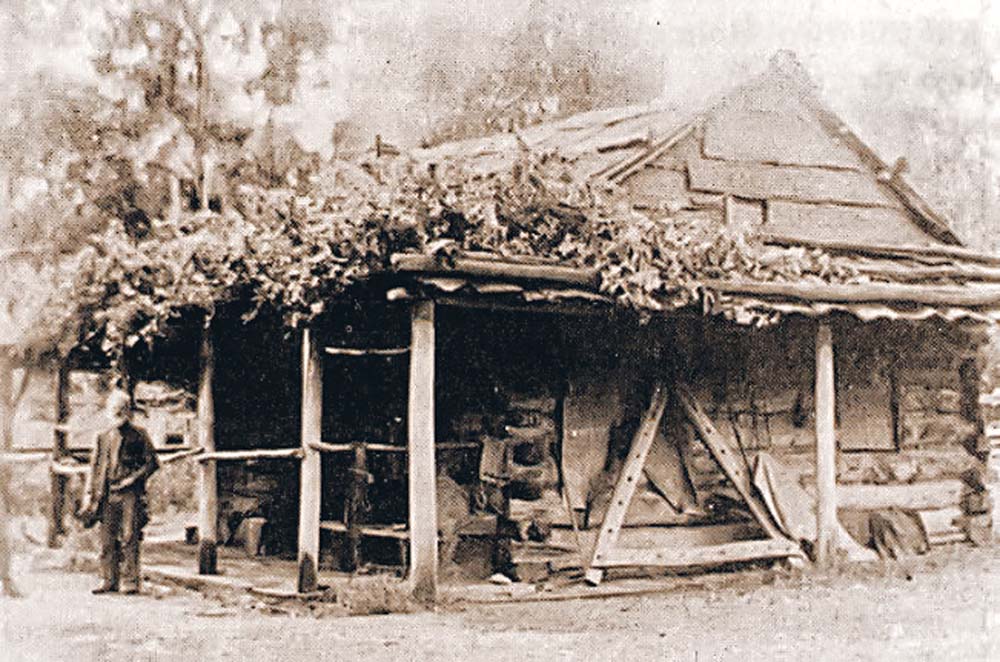

Once described as “the most isolated homestead in Victoria”, the Wonnangatta Station was a cattle property located in the remote Wonnangatta River valley. Access was by horse or foot only.

The nearest population centres were the goldfields towns of Talbotville, about 20 miles (32km) away, Grant and Dargo to the south-east, and the larger town of Mansfield, about 80 miles (130km) distant over the Great Dividing Range.

The station had been established in the 1860s by Oliver Smith, an American who came across the valley when prospecting for gold. Smith’s common-law wife Ellen and her son Harry joined him and a homestead was built near the junction of the Wonnangatta River and Conglomerate Creek. Ellen subsequently died in childbirth and Smith sold out to William Bryce, eventually returning to the United States.

The Bryce family, which eventually included 10 children, then occupied the Station and built a new homestead; Ellen’s son, Harry, moved down the valley and established himself at Eaglevale. The Bryce family remained at Wonnangatta for over 40 years until Mrs. Bryce died at the age of 78 in 1914. The Mansfield owners then bought the property and installed Jim Barclay as manager.

What was the background to the murders?

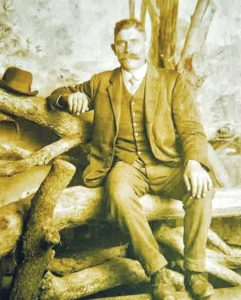

Jim Barclay led a solitary existence at Wonnangatta and his only close friend was Harry Smith at Eaglevale. By late 1917 he had convinced the owners (Phillips and Ritchie) that he needed a hired hand who could do general work around the property and also cook for the extra station hands needed during busier times such as cattle musters.

Labour was in short supply because of the war and Barclay would have had little to choose from; on 14 December, 1917 61-year-old John Bamford from Black Snake Creek (near Talbotville) started work.

Bamford was not well regarded in the area where he had lived for 20 years: he was variously described as “surly”, having “a quick temper”, and even being suspected of having murdered his wife. The storekeeper at Talbotville (Albert Stout) is known to have warned Barclay “not to be drawn into any arguments with Bamford.” Be this as it may, a stockman who visited Wonnangatta in December 1917 recalled that the two seemed to be on good terms.

Barclay and Bamford were last seen alive in late December 1917. They had been to Talbotville to cast their votes in the Reinforcement Referendum, the second of the two conscription referenda in Australia during the First World War. They stayed the night at Talbotville, before leaving for Wonnangatta early in the morning of 21st December.

How were the murders discovered?

On 22nd January, 1918 Harry Smith arrived at Wonnangatta Station about 6pm to deliver mail. Barclay and Bamford were both absent but the words “Home tonight” were written in chalk across the kitchen door. Smith stayed two nights but when no-one appeared he went on to Eaglevale on the 24th January, 1918.

In the late afternoon of 14th February, 1918 Harry Smith returned to the Wonnangatta homestead to find it still deserted and the mail sitting where he had left it on the kitchen table. Furthermore, Barclay’s favourite dog, “Baron”, was starving and neglected. Smith briefly searched the area but left for Dargo the next morning to raise the alarm. From there the owners in Mansfield (Phillips and Ritchie) were telegraphed.

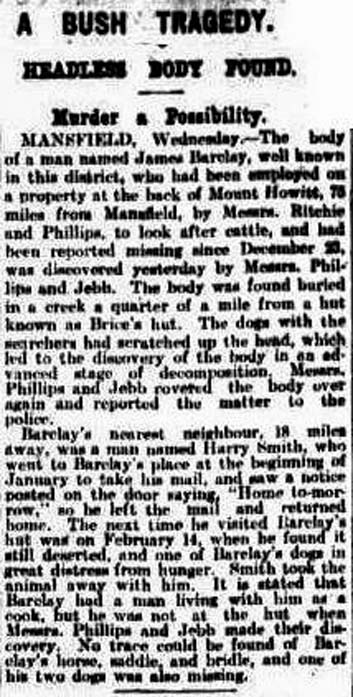

On 23rd February, 1918 Phillips and stockman Jack Jebb arrived at Eaglevale from Mansfield and the next day, accompanied by Harry Smith, they returned to Wonnangatta. After a prolonged search they found a badly decomposed body near Conglomerate Creek, about 420 paces from the homestead. The body had been buried in a shallow grave but wild animals had apparently uncovered it; only the skull was protruding from the sand. From the remaining pieces of clothing, a belt and a tobacco pouch Smith identified the body as that of Barclay. After the body was reburied, Phillips returned to Mansfield and informed the police. From Melbourne Detective Alex McKerral was despatched, together with Constable Ryan who had grown up in the district and had good local knowledge.

Several days later the police party set out on the 80 mile ride from Mansfield to collect Barclay’s remains and return them for a post-mortem at Mansfield hospital. On arrival at the homestead another disaster was narrowly averted when two of the policemen decided to prepare an evening meal of bacon and eggs. They sprinkled pepper from a tin on the mantlepiece and were about to eat when the eggs turned a peculiar colour. The “pepper” was in fact rabbit and dingo poison, and the case had almost taken a very dramatic twist!

Police found a shotgun in Barclay’s room; although it had been discharged recently there were no bloodstains in the room. His bed was in a state of disorder. Bamford’s room was also in a state of disorder, and his horse, “Thelma”, saddle and some belongings were missing.

On the return journey with the remains the police party came across “Thelma” running wild without a saddle or bridle on the Howitt High Plains.

The post-mortem found that Barclay had been murdered by a shotgun blast in the back and had been dead for several weeks at the time of discovery. At the inquest that followed Detective McKerral said “I am of the opinion that Barclay and Bamford had an argument over working matters and that Bamford loaded the gun and shot Barclay. He removed his working clothes and dressed himself in Barclay’s suit, which is missing, saddled his horse and, after dragging the deceased to the creek, rode the horse away.” The verdict of the inquest was murder by person or persons unknown.

Jim Barclay’s body was released to his extended family and he was buried in the Tyabb cemetery in Hastings on 9th March,1918. On March 16th The Leader carried the following report:

HASTINGS. The remains of James Barclay, the victim of the Mt. Howitt tragedy, were on Saturday buried in the local cemetery. The deceased’s brother is an orchardist here. Many of the deceased’s schoolmates attended the funeral. The deceased, who was 49 years of age, left Hastings for the North-East when a youth. He has the reputation of being remarkably expert in the mustering of cattle. A wreath composed of leaves from Barclay’s favourite tree at Wonnangatta Station was placed on the coffin.

To mark his resting place the family added to Jim’s parents’ gravestone the words:

AND OUR DEARLY LOVED BROTHER JIM.

JANUARY 1918 AGED 48 YEARS

With the notoriety the murder caused, the simple wording showed the family wanted to place the tragedy behind them.

Did they find Bamford?

Bamford was the obvious suspect-perhaps too obvious-and a state-wide search was soon underway. A reward of 200 pounds was offered by the government for information regarding Barclay’s murder. The police search was side-tracked by repeated reports of sightings of the suspect from all over the state. Furthermore, two men were apprehended at the time, each believed to be Bamford. The first was arrested by Constables Farley and Ryan of Frankston police station: they received information that a man answering to the description of John Bamford had been seen between Seaford and Carrum. The police found the man at Carrum but, according to a report in The Leader, when Constable Ryan questioned the suspect he “found that he was apparently out of his mind.” Due to his mental state, the constable arrested the man on a vagrancy charge and took him to the Frankston lock-up. The man told police that his name was John Thomas and that “he had just arrived from heaven to save the world.” The Frankston police were quick to advise investigators that the man arrested was not John Bamford.

Then on 11th March, 1918 another man believed to be Bamford was apprehended at Balloong, near Yarram. He attempted to elude police but, when arrested, confessed to the murder of Barclay. He was charged and the following day Detective McKerral and Constable Hayes from Dargo arrived at Yarram to transport the prisoner back to Melbourne. Constable Hayes knew Bamford and, as soon as he saw the prisoner, he realised that this was not the missing man. It turned out that “Bamford” was in fact a vagrant who was suffering from delusions.

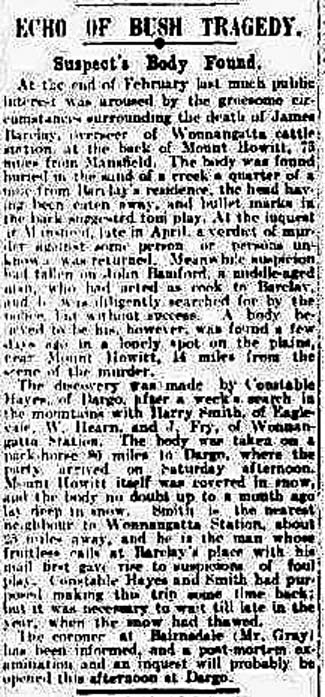

The winter months made searching difficult. Then in early November, 1918 Constable Hayes, together with local bushmen Harry Smith, William Hearne and Jim Fry, was searching the Mt. Howitt area when Hearne noticed a boot protruding from a pile of logs near the Howitt Plains hut. Under the pile they found Bamford’s body. The reason for the search of Mt. Howitt was ostensibly that Harry Smith had dreamed that Bamford would be found there! As the route to Mansfield was still under snow, the body was taken to Dargo. The post-mortem found a bullet lodged in the skull and, again, at the inquest a verdict of murder by person or persons unknown was made.

So who killed Jim Barclay?

Up to this point it had been taken for granted that Barclay had been killed by Bamford. One might have thought that the discovery of Bamford’s body provided him with a reasonable alibi. This was not the case and he remained the chief suspect: speculation now followed the line that Bamford did in fact shoot Barclay and he in turn was hunted down and shot by some friend of the manager in a revenge killing. Police suspicion naturally fell on Harry Smith, especially as his “dream” had led to the finding of Bamford’s body. But there was no direct evidence. In addition he would have had to carry out a complex deception about the discovery of Barclay’s body, and he was present at the discovery of Bamford’s. It is also unlikely that he would have knowingly allowed the body of his friend Jim Barclay to lie where the murderer left it and be disturbed by animals for three weeks. Smith was not charged.

A variation of the “Bamford did it” theory expressed by one writer suggests that Bamford killed Barclay following an argument but, full of remorse, he committed suicide when he reached Howitt Hut. This seems unlikely as it does not accord with the general view of Bamford’s temperament. Besides, there was no sign of the revolver in the vicinity of the Hut, and Bamford could hardly have buried himself under such heavy logs.

Another point which suggests the killer was not Bamford is that he was quite a small man and yet Barclay was tall and strongly built. It seems unlikely that he could have dragged the body of Barclay 420 paces to the burial site.

The second main theory is that the two men were the victims of stock thieves who had been caught at work. The police report refutes this, pointing out that the only stock missing from Wonnangatta was Bamford’s horse, and that had been recovered on Mt. Howitt. Be that as it may one author even names the killers as Jack and Sid Beveridge, renowned cattle duffers from the Buckland area; he maintains that Sid admitted his guilt to a neighbour in his old age. It is apparently part of the folk lore on the Buckland that Jack Beveridge courted a local lady named Dolly Eccleston for 40 years and he visited her every Sunday night wearing Jim Barclay’s good suit! This was the suit listed by Detective McKerral as “missing” at the inquest.

This second theory has an interesting variation expressed by one author. He suggests that Jim Barclay was a cattle thief who would stop at nothing to make money and become as successful as his brother John. This obsession led to him going too far with someone’s livelihood and as a result he was murdered. The regard in which Barclay was held by Arthur Phillips and others would suggest that this variation of the cattle thieves theory is not plausible

The third theory that is at times presented is that Jim Barclay was a ladies man who was killed by a jealous husband. Although one author discredits this suggestion as “the work of a novelist who had obviously done little or no research in the matter”, another author names the object of Jim’s affection as Annie Klingsporn from Merrijig. The killers were her husband, Robert Klingsporn, and his brother-in-law, Jack Ware. This theory also has several variations: one is that the killers were in fact Robert Klingsporn and one or both of his brothers; another is that Jim Barclay had not honoured promises made to Robert Klingsporn’s sister, Fanny, and was made to pay the price for his indiscretions. The Klingsporns and Jack Ware were highly respected in the area and this seems a very unlikely theory. Besides Jim Barclay had been at the remote Wonnangatta Station for almost three years and a liaison with Annie, Fanny or some other lady would seem to be highly unlikely. The current descendants of the Barclay family who still live in the Hastings area not only stress the remoteness angle, but also state that Jim’s brother, John, was firmly of the view that Jim was “not that sort of a person.”

The Wonnangatta murders were the subject of many yarns in pubs and around campfires in the high country; many claimed to know who had killed Barclay and Bamford but no-one would tell. The mystery remains.

What happened to Jim junior

After he finished schooling, Jim Barclay’s son, Jim junior, spent many years working for Harry Smith at Eaglevale. Harry died in 1945 aged 86 and left the property to young Jim. He lived there until he eventually sold it and moved to Stratford where he worked for the Country Roads Board. At the time he had set up in one of the Country Roads Board’s huts but one day a fire broke out which destroyed the hut. Jim managed to escape unscathed but unfortunately a lifetime of Harry Smith’s prized possessions, including documents and letters, all went up in smoke. The truth as to what really happened at Wonnangatta Station may well have disappeared as well. Jim Barclay junior married Lottie Binns later in life and he lived at Lindenow South after his retirement from the Country Roads Board. It was there that he was visited by one author (Wallace Mortimer) and his enigmatic comment on the murders was “It was a long time ago and both the murderers are long since dead. It’s all best forgotten.” He followed Mortimer out to his car and his parting words were “You know, Harry Smith told me that the men who killed my father were Robert Klingsporn and Jack Ware.” This stunned Mortimer: was the least likely explanation perhaps the correct one? Young Jim died at the age of 77 on 27th May, 1987.

After he finished schooling, Jim Barclay’s son, Jim junior, spent many years working for Harry Smith at Eaglevale. Harry died in 1945 aged 86 and left the property to young Jim. He lived there until he eventually sold it and moved to Stratford where he worked for the Country Roads Board. At the time he had set up in one of the Country Roads Board’s huts but one day a fire broke out which destroyed the hut. Jim managed to escape unscathed but unfortunately a lifetime of Harry Smith’s prized possessions, including documents and letters, all went up in smoke. The truth as to what really happened at Wonnangatta Station may well have disappeared as well. Jim Barclay junior married Lottie Binns later in life and he lived at Lindenow South after his retirement from the Country Roads Board. It was there that he was visited by one author (Wallace Mortimer) and his enigmatic comment on the murders was “It was a long time ago and both the murderers are long since dead. It’s all best forgotten.” He followed Mortimer out to his car and his parting words were “You know, Harry Smith told me that the men who killed my father were Robert Klingsporn and Jack Ware.” This stunned Mortimer: was the least likely explanation perhaps the correct one? Young Jim died at the age of 77 on 27th May, 1987.

The Wonnangatta Station homestead was accidentally burnt down by careless bushwalkers in 1957. Some stockyards and the old cemetery survive. Today the area is part of the Alpine National Park, and is only accessible by 4WD, horse, or foot. The nearby mining towns of Grant and Talbotville have disappeared.

Credits

Thanks to Jennie Bryant of Tyabb for her assistance; her grandmother was a niece of Jim Barclay.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Some of the books on the subject are:

- Leydon, Keith and Ray,Michael “The Wonnangatta Mystery:an inquiry into the unsolved murders.” Warrior Press, 2000.

- Mortimer, Wallace “The History of Wonnangatta Station” Spectrum Publications,1980.

- Mortimer, Wallace “Wonnangatta Station-the Next Twenty Years.” McPhersons, 1995

- Mortimer, Wallace “Who Killed Jim Barclay?” 2009

- Ricketts, John J. “Victoria’s Wonnangatta Murders” E-Gee printers, 1993.