By Muriel Cooper Photos Yanni

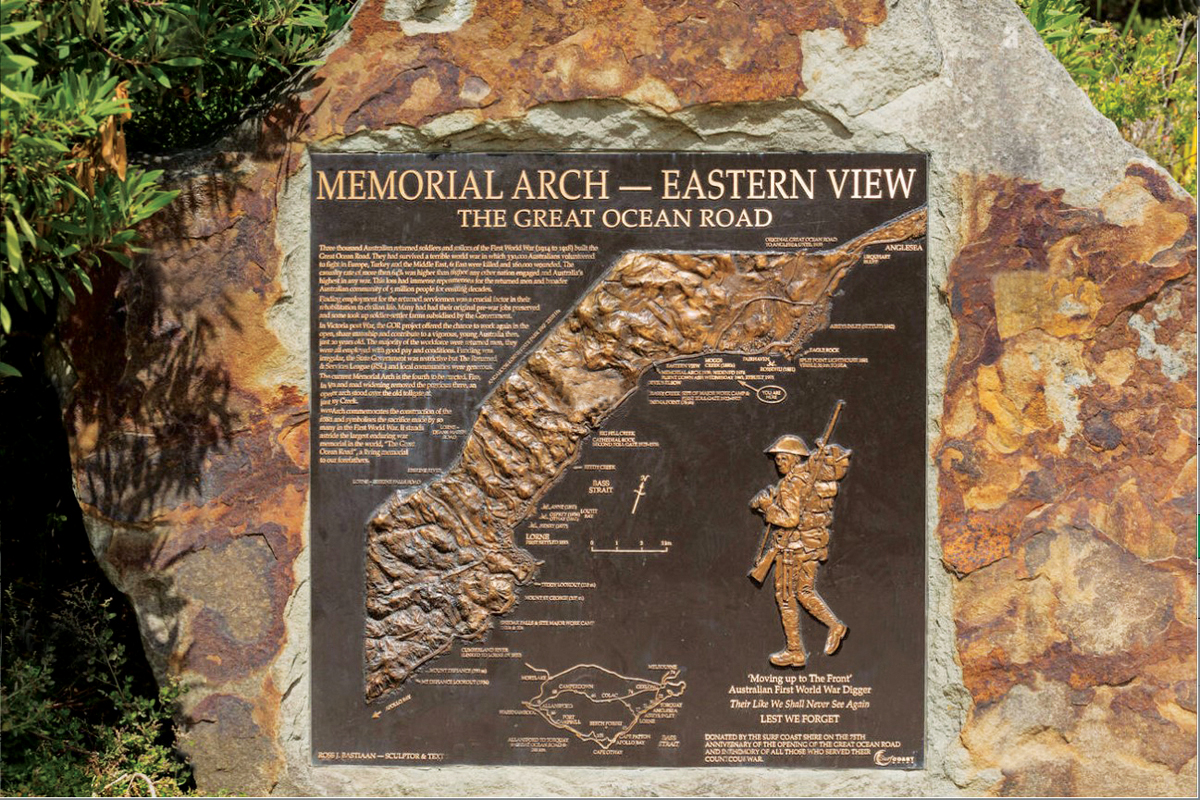

In a Dandenong foundry, a fiery crucible pours 85 kilos of molten bronze into an impression in special sand to form a historical plaque that will hopefully stand for centuries.

Bayside periodontist Dr Ross Bastiaan uses his dental tools in his Merricks North workshop to finely sculpt and craft landscapes, figures and text describing Australia’s military history.

Ross was mentored by the famous Frankston sculptor Ray Ewers who was willing to take an inexperienced periodontist on board. “I’m no Michelangelo, but I can make an image look like a person,” he laughs.

“I do it because young people today don’t read as much as they used to but they react to an image. I finished one just last month for Messines in Belgium, where Robert Grieve won his Victoria Cross.”

“It was almost a disaster. I finished it just in time and got it on the plane – it got to Brussels, and no one came to collect it! It sat in the storeroom because the stonemason didn’t have a permit, so they sent it all the way back to Australia and the ceremony was in a week’s time. So the foundry did a second casting, sent it, and it arrived within one day of the ceremony.”

Ross smiles ruefully. “For the one-hundredth anniversary of Gallipoli, about ten weeks before the ceremony, nine of my ten bronzes were stolen by Romanian Gypsies, crowbarred out to melt down for the bronze. The Australian Government generously gave me the funds to recast them.”

In South Africa, Ross’s plaques have handles on them so they can be removed and are only replaced for Anzac Day.

Eminent people, from Bob Hawke to John Howard to Clifton Pugh, to the great Weary Dunlop, have followed Ross on his missions to install the plaques.

Ross first became interested when he was doing his masters degree in periodontology at London University in 1977. The clinical photographer there presented him with a cache of old negatives that he had rescued from a skip in Fleet Street that he thought were from WW1. Ross was excited since he’d been raised in a military family and partly raised by a Victoria Cross winner, and his father was in the Dutch Navy.

When he held the negatives up to the light, Ross recognised Gallipoli and Achi Baba (a Gallipoli landmark). Along with writer Peter Pederson, he released a book about the photographs titled ‘Images of Gallipoli’. While in Gallipoli researching the book, Ross realised there was no historical record in English of Australia’s part in the war.

He applied to the Turkish Government for permission to erect ten bronze plaques and number them around the battlefield. “Everywhere you stand, you can read, ‘To the left were the Turks. To the right were the Australians,’ so you know what you’re looking at,” he explains.

Australian historical plaque installed along the Great Ocean Road

In 1990, accompanied by fifty-three Gallipoli veterans, Ross returned to install them.

“It was a moving moment,” he recalls. “These old men would never see this area again. Many of them had never been there again since they landed in 1915. We found cemetery markers of their mates.”

“The big one for me was the Kokoda Trail. When the defence chief at the time, General Peter Gration, asked me if I’d do it (I was forty), the closest thing I’d come to fitness was walking from the back door of the surgery to the car. I went to a bulk store and bought a pair of boots three days before I left. I had a team of forty carriers, and we went through the jungle over nine days and erected the bronzes, and I’m proud to say they’re still there.”

Ross works at no charge as his commitment to Australia, strongly believing everyone should give back. Over the years, he has raised over one and a half million dollars, praising the generous people who’ve made it possible.

Negotiating with governments hasn’t been plain sailing. In Libya, Ross had to negotiate with Gaddafi, and after one hundred and fifty battlefields, he still hasn’t done Syria and Vietnam. In Singapore, Ross had to change the text to tone down the cruelty of the Japanese of the time. “You do have political sensitivities because the world’s moved on,” he says.

Ross went on to record Australian history and began installing plaques along the Great Ocean Road, which took him thirteen years to complete. “Some of the most difficult bureaucrats I’ve encountered anywhere have to be the Australians – local councils,” he says wryly.

Ross’s imagination was also captured by the Burke and Wills expedition. He erected six bronze works along the actual route. The other was The Kokoda Track in the Dandenong Ranges which has proven to be unbelievably popular.

“When I started, about 3,000 people walked the One Tree Hill track each year, and there are something like 80,000 people walking it now. I replicated it in Brisbane, Canberra and Perth.”

One close to Ross’s heart is at Wilson’s Promontory, where the Australian Commandoes trained, including his uncle. Of his 293 plaques in over twenty countries, he says the one that moved him the most was one erected on the battlements of Menin Gate at Ypres in Belgium.

“It symbolises the futility of the Great War. By the time I got to Ypres, I was so furious at the loss of life and the destruction of nations I couldn’t help but reflect it in the wording. It looks out over the road that our men walked to go into battle, and 60,000 of them didn’t come back I thought this was a really sad indictment of the Great War, and I felt quite emotional at erecting it. It was the most important plaque to me.”

“The Great Ocean Road is probably my favourite. The great emotional pleasure is knowing you’ve left something there for another generation.”