By Peter McCullough

In November 1888, Dr Charles William Rohner MD opened his practice in Hastings. He was the town’s first doctor. On 9 January 1890, he disappeared without trace. At the time there were several theories about his fate but the mystery remains unsolved.

***

Who was Dr Rohner?

Charles William Rohner was born in Austria on 14 December 1832, the son of Johann Martin Rohner and Anna Maria (nee Gmeiner). He studied medicine at the University of Prague, graduating in 1858. Dr Rohner then travelled to England where he boarded the Queen of the East in 1859 as an unassisted immigrant bound for Australia.

Where did he practise?

Dr Rohner appears to have headed to northeast Victoria on his arrival, as the following advertisement started to appear regularly in the Ovens and Murray Advertiser from October 1859:

“Dr Rohner, Surgeon and Accoucheur, has succeeded to the practice, and taken the residence of, Dr Muller, Stanley, where he may be consulted daily.”

By 1862, Dr Rohner had shifted his practice to Chiltern and on 20 May of that year, he married Margaret Emmeline Edmonds in Albury. The Rohners had eight children, most of whom were born in Chiltern. Although his somewhat eccentric behaviour and beliefs earned him the scorn of some locals and the press, Dr Rohner was none-the-less given a public farewell at the time of his departure in 1876. In fact, the following paragraph appeared in The Argus:

“Chiltern. Dr Rohner, who is leaving the district after a residence of 17 years, was entertained at a banquet at the Star Hotel today. An illuminated address, handsomely framed, was presented to him. About 40 gentlemen were present. Mr B J Bartley, president of the shire council, presided.”

(It could be said that the doctor left his mark on the town as there is still a Rohner Street in Chiltern)

Although it was stated that Dr Rohner’s term was 17 years, this would have included his time in Stanley. It would also have included a period in New Zealand around 1865. It is unclear as to the purpose of his visit (work or vacation?) or how long he spent there. However The Argus of 21 January 1865 reported:

The Constitution of Wednesday says: “Concerning the moa, Dr Rohner, who a day or two ago arrived in Chiltern from New Zealand, says out of a large quantity of bones transmitted some months ago to some celebrity in Frankfurt, two complete skeletons were set up….”

So among his other areas of expertise, the good doctor also purported to be an expert on an extinct flightless bird from across the Tasman!

From Chiltern, Dr Rohner moved to Hamilton and while there he attended an accident involving the wife of Alfred Tennyson Dickens (son of Charles). Mrs Dickens was killed when thrown from her carriage after the horses bolted (Hamilton Spectator 14 December 1878). His departure from Hamilton was apparently quite amicable for on 25 January 1879, the local paper carried the following item:

“Presentation to Dr Rohner. Yesterday morning, about twenty members of the Hamilton Chess Club and friends of Dr Rohner assembled at the Victoria Hotel to take farewell of him… In handing over the gift (three handsomely bound volumes of the History of England accompanied by a splendid portrait of Her Majesty) Mr Laidlaw complimented Dr Rohner, if not actually as founder of the club, at all events as a gentleman who had done more than any other to promote the interests of chess in the district…”

This ability at chess was apparently passed on to his second son, William Aberlard, for on the 1 February 1879, the Williamstown Chronicle had a story about 12-year-old Willie Rohner whom it described as a “chess prodigy and composer”. The article goes on to say: “His father, the worthy and genial Dr Rohner, also favoured our president (ie of Williamstown Chess Club) with some lively skirmishes over the checkered board before his departure for Bright.”

The next decade or so of Dr Rohner’s life appears to be unsettled for from Bright he moved to Benalla, returning to Chiltern for a second term in 1880.

On 27 May 1884, the North East Ensign reported that Dr Rohner had revived the wife of a cabman in Tungamah who had taken poison by mistake. Then on 13 January 1885, the Ensign stated:

“Dr Rohner, well known in Benalla, currently residing in Tungamah, has been appointed health officer to the Yarrawonga Shire Council.”

The Tungamah stay must have been short for the South Bourke and Mornington Journal on 3 August 1887 reported that an item in the minutes of the Phillip Island Shire Council stated that “Dr Rohner MD reported a case of diptheria at Griffiths Point”. However, by November 1888, the first of his regular advertisements appeared in the above-mentioned newspaper stating:

“Dr C W Rohner MD has commenced the practice of his profession in Hastings, and may be consulted at his own residence, Mistress Rennie’s, opposite Prosser’s Store.”

The departure from Phillip Island was full of rancour and, in 1889, the Journal published Dr Rohner’s letter to the council lamenting the non-payment of “…the debt of 100 pounds which these good and honest Christians owe me for work and labour done for them and the public without fee or reward…”

Dr Rohner stated that: “The councillors are just about as fit to act in the capacity of a local board of health as they are unfit to keep a pigstye clean.” For an advocate of spiritualism, he was not beyond turning to the Bible for some support: “I call upon the holy spirit of Moses to proclaim the eleventh commandment of his hitherto defective catalogue, saying unto the children of the earth-from thundering and spitfire Mt Sinai: ‘Man. Thou shalt be fair and just in thy dealings with thy brother’.”

What sort of person was Dr Rohner?

The tone of his correspondence suggests a degree of volatility in his temperament. The word “eccentric” appears regularly in the newspapers and, the public send-offs notwithstanding, he ruffled plenty of feathers. Three issues that gained him more than a little publicity were:

1. The skull of John McCallum.

This drama was reported in The Argus on 9 January 1871, and then again three days later:

“Strange Conduct of a Coroner. Dr Rohner, deputy coroner, wrote to the Ovens Advertiser referring to a document read out at a recent meeting of the Indigo Road Board, calling attention to the appropriation by the deputy coroner of the skull of the late John McCallum, formerly a member of that board, and who died some time back in the Chiltern lockup.

“The document was signed by the widow of the deceased, Margaret McCallum, and is said to have contained some exaggerated statements, amongst others to the effect that the skull referred to had been exhibited by the coroner in several places as a curiosity. Nettled by these accusations, Dr Rohner had replied and… in a most ungentlemanlike manner, he endeavoured to insult and wound the feelings of Mrs McCallum. The facts of the case are said to be that Dr Rohner retained a piece of the late Mr McCallum’s skull, not the whole skull, as stated in the letter to the Indigo Board, which he exhibited on various occasions to a few of his friends.”

The Argus 12 January 1871: “Another extraordinary letter from Dr Rohner, deputy coroner of Chiltern, appears in the Federal Standard on the subject of the skull of the man McCallum. It is headed ‘Numbskulls and other Skulls’ and contains the writer’s reply to a recent letter written by Mr Herman Ruppin.

“The following is a specimen of the doctor’s controversial style: ‘What I mean to stamp as a deliberate and bare-faced falsehood is his (Mr Ruppin’s) assertion that I showed him the bone in question before Mr John McCallum’s funeral… After this, never trust a Jew. They are bound to have their pound of flesh, however little they may care about bones’.”

The excuse that he only exhibited a portion of Mr McCallum’s skull did not impress the Indigo Road Board, particularly as at one time Mr McCallum had been a colleague. Within days the matter was mentioned in parliament and on 4 March 1871, The Argus reported: “Dr Rohner’s removal from the commission of the peace and the office of deputy coroner is gazetted.”

(Footnote: According to local folk lore, Dr Rohner kept a skull on one corner of his desk while he was in practice in Chiltern. Did Mr McCallum become a permanent exhibit?)

2. His advocacy of spiritualism.

Dr Rohner would have been loved by journalists at The Argus for he always seemed to be good for a story. This item appeared in that paper on 28 October 1871 when the skull story was fresh in everyone’s mind (If it doesn’t make sense, please do not contact Peninsula Essence for an explanation):

“The eccentric Dr Rohner of Chiltern is still lecturing on the subjects of spiritualism and magic. At a recent lecture he mentioned that… as a statistical curiosity, that to the best of his knowledge there was not at present a single scientific magician in Australia, only a few in America and England, but there was a great number in France and Germany, in which latter countries the science of ‘Haute Magic’ was always considered the keystone of the education of a thorough philosopher.

“The doctor took the opportunity to state that he was authorized by the brotherhood to which he belonged to introduce new members to their society, the leading principles of which were light, intelligence, progress, love and wisdom, linked together with moral rectitude, genius, harmony and beauty”.

“The following caution to spiritists,” says the Ovens Advertiser, concluded one of the most remarkable lectures ever delivered in Chiltern, if not the colony: ‘Yes, spiritists, the spirits which speak to you in the tables are the spirits of your blood. You fatigue and exhaust yourselves only to put your own soul into the wood of your furniture, like those priests of Mexico who thought they were giving a soul to their idols by daubing them over the smoking blood of human victims. What you are doing now was done long before the birth of Christ; it was done and is still done in India; it is, moreover, done amongst the savages, where the jungles form a circle round the altar of their gods with ghastly heads, the hair of which is dripping with blood, and you only magnetise your furniture by impoverishing your brain as well as your heart. Why would you be in such a hurry to see the spirits of your departed friends; surely you will see them soon enough when your proper time to see them has come, without degrading your faculties to the lowest degree of madness. Believe me, it is a false religious sentiment to build your arguments for the immortality of the soul upon the spurious facts of spiritualism’.” (The Argus, 18 October 1871)

Although all of this may appear to be incomprehensible, Dr Rohner’s contribution to the concept was widely known for on 26 August 1884 The South Australian Register, under the heading ‘The Freethought Battle’, quotes Dr Rohner “…who has made a careful investigation of spiritual phenomena”.

Whether or not it was linked with his views on spiritualism is not known, but Dr Rohner frequently warned of the dangers of “animal magnetism which can produce sleep, insensibility… even death”. (The Argus, 14 September 1871)

How all of this was received by the ordinary man in the street in Chiltern can only be guessed at. No doubt a few heads were shaken vigorously. He seemed to be involved in a number of the so-called ‘friendly societies of the North East’ and as late as 30 March 1883, the North East Ensign announced: “Dr C W Rohner has been appointed Medical Officer of the Benalla Lodge of Oddfellows.”

A few years earlier The Argus carried a few lines that suggested Dr Rohner’s relationship with the societies was not always friendly:

“MEDICAL- In reference to an advertisement that lately appeared in The Argus inviting ‘Applications from medical gentlemen to attend the united societies at Wandiligong’, the following has already appeared in the Ovens and Murray Advertiser: AOF Court Little John No. 4001.

“The members of the above court at Bright, Wandiligong and the surrounding district generally are hereby notified that, notwithstanding the advertisement from the united societies at Wandiligong, Dr C W Rohner still continues to occupy the position of court surgeon. (The Argus, 8 August 1879).

3. Opposition to small pox vaccination.

This also caused some friction with authorities and his views were widely known. An article on small pox vaccination which appeared in The Hobart Mercury on 5 September 1881 mentioned that Dr Rohner of Victoria was “a most determined opponent”.

Be this as it may, a month later Dr Rohner was shown in an unfavourable light by Sir Bryan O’Loughlin in the budget debate: “While it is necessary to be prepared for an outbreak of small pox, no possible good can come from raising false alarms. We have had several of these already.

“Dr Rohner of Benalla, for example, reported two cases of supposed small pox, which proved, upon investigation, to be nothing of the kind. This misdirected zeal caused a good deal of alarm in the district and much personal inconvenience… In view of the needless trouble and alarm occasioned by the Benalla episode, Inspector Montfort has suggested to the Central Board of Health that Dr Rohner be requested to report in future to the local police any suspicious cases that may come under his notice…” (The Argus, 6 October 1881)

What was Dr Rohner’s state of mind when he arrived in Hastings?

Looking at the events that occurred after 1876 when he was given the public farewell following his first term in Chiltern, it would be reasonable to suggest that Dr Rohner’s life was unsettled; he had shifted his practice a number of times and his departure from Phillip Island had been unpleasant. Furthermore, the unexpected death of his eldest son undoubtedly took its toll. This tragedy was reported in the Euroa Advertiser on 17 May 1889:

“We are sorry to chronicle the death of Mr Charles Rohner which took place at Shepparton on Sunday last, from typhoid fever. Mr Rohner, who was the son of Dr C W Rohner, for many years a resident of this town, was well known in Benalla, where his mother still resides. He was up at Benalla on Monday with the Shepparton Fire Brigade, taking part in the Fire Brigade Demonstration. The news of his death caused a widespread feeling of regret.”

When did the doctor disappear?

The Victorian Police Gazette of 15 January 1890 contained the following missing person notice: “Enquiry is requested for Charles Henry (sic) Rohner who is missing from his home, Hastings, since 9th instant. Description: Austrian, medical man, slightly foreign accent, 58 years of age, 6 feet 1 inch high, stout build, erect gait, dark hair turning grey, grey beard, whiskers and moustache, wore grey tweed sac-suit, brown tweed hat and lace-up boots. Well-known in the North-Eastern district. Fears are entertained for his safety as he was in a melancholy state of mind prior to his disappearance.-14th January, 1890.”

So what happened to Dr. Rohner?

It would seem that his disappearance coincided with the unexpected arrival in Hastings of his wife from whom he was estranged. But what actually happened to him? There are two main schools of thought: suicide (as believed by his friends in the north-east) or he “shot through” (according to “the locals”.) A return to Austria was even suggested by some supporters of this second theory. The two opposing views were well expressed in the language of the day in the respective local papers and it seems appropriate to quote from them:

It would seem that his disappearance coincided with the unexpected arrival in Hastings of his wife from whom he was estranged. But what actually happened to him? There are two main schools of thought: suicide (as believed by his friends in the north-east) or he “shot through” (according to “the locals”.) A return to Austria was even suggested by some supporters of this second theory. The two opposing views were well expressed in the language of the day in the respective local papers and it seems appropriate to quote from them:

1. Suicide theory

“Disappearance of Dr. Rohner. With respect to the mysterious disappearance of Dr. Charles W. Rohner, the opinion in Benalla is that he has committed suicide. A letter dated Hastings 20th December was received from him by Dr. F. Wurm, jeweller, who besides being a fellow countryman, was one of his personal friends. The communication, written in German, was marked throughout by a despondent tone. The writer stated that a dark cloud, which he was afraid he was powerless to absolve, had haunted him for some time, and he went on to speak of the happiness to be obtained in the next world as in every sense preferable to the present. He referred especially to the death of Mr. Crawford, a well-known resident of Benalla, who committed suicide by drowning a few weeks ago, and gave it as his opinion that his (Crawford’s) act of self destruction was due to the influence of evil spirits which he had come in contact with. It is also known that Dr. Rohner felt very keenly the death of his eldest son, who fell a victim of typhoid at Shepparton some months ago, and in fact, taken in conjunction with the strange communication referred to, forces Mr. Wurm and others to the opinion that the doctor has done away with himself. For some time he practised his profession in Benalla. He was a man of exceptional literary attainments, and was perhaps best known to most people as a strong opponent of vaccination.” –Euroa Advertiser, 24th January, 1890.(also The Argus.)

2. “Shot through” theory

“Hastings. The alarm which has been created in some men’s minds by the departure of Dr. C.W. Rohner from Hastings is not, I venture to predict, justified by the facts of the case. An absurd article appeared in a Melbourne journal leaning to the side of the terrible and desperate-those sentiments so dear to the dull and barren soul of a reading public. There was no mystery about the doctor’s disappearance, as the cause thereof was distinctly proved by the arrival of his wife the same afternoon, from whom he had been for years estranged, and the simple fact that he gave no notice of his departure and left no address is accepted as conclusive evidence that he has come to an untimely end. The writer in the article referred to says the doctor left his watch and jewellery behind. Now it is a well-known fact that he did not possess or wear any jewellery. The writer also says that on the following day the police were informed, whereas three days elapsed before the subject was mentioned to the police, and the scribe asserts that the police stated that the doctor had not left by train, coach, boat or any conveyance whatever. Constable McCaig said nothing of the sort: he merely said that he was unable to trace the doctor after the lapse of three days. The translation of the words in the diary should be ascertained to be correct beyond the possibility of doubt, as there appears to be a difference of opinion on the subject. It is also said by the writer that the police constable scoured the country (whatever that may mean) and that he searched about the pier, insinuating, but not daring to say, that the water had been dragged. Now I venture to affirm that the conclusion arrived at by those lovers of the mysterious is not borne out by the facts of the case, which are extremely simple in themselves, and that all the reasoning alluded to above is incorrect and the outcome of a morbid imagination, desirous to please the admirers of the sensational. It is true that the doctor drew out of the bank a small balance and gave it to his daughter, and it is also true that he was known to have in his possession a considerable sum a short time previous to his departure. Those who conversed eight hours previous could notice nothing peculiar in his manner. I have been intimately acquainted with the doctor for the last 15 months and I have no fear for his safety, the cause of his departure being to avoid a domestic conflict but what his ulterior plans may be I know not, and the mystery which it is attempted to attach to the matter, I regard as absurd.”-South Bourke and Mornington Journal, 29th January, 1890. It should be mentioned that, because of the “considerable sum” which Dr. Rohner was apparently carrying, some locals wondered whether he may have been murdered. This suggestion, however, does not appear to have had any support amongst the various newspaper correspondents.

Was there ever any trace of Dr. Rohner?

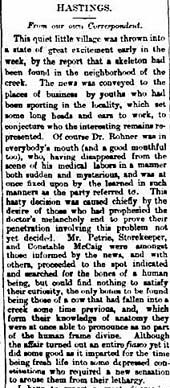

For some months the residents of the little seaside village pondered the fate of their first doctor. Then in early May some boys playing in Kings Creek made a discovery; word spread quickly that they had found Dr. Rohner. The excitement soon abated when the bones turned out to be those of a dead cow. The Hastings correspondent of the South Bourke and Mornington Journal, who had so strongly advocated the “shot through” argument in January, was rather caustic in his comments (see previous page) While there has been on-going speculation as to Dr. Rohner’s fate, one fact is clear: there was never any registration of his death in the Victorian death index.

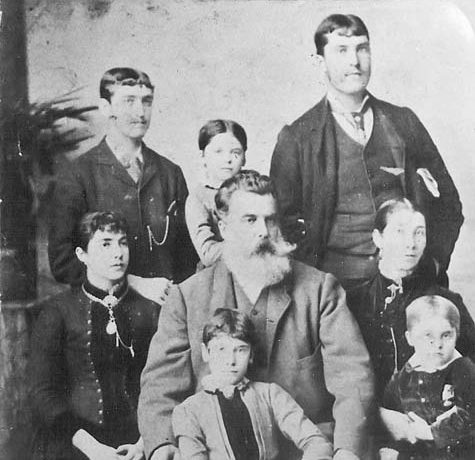

What of Dr. Rohner’s family?

As mentioned, Dr. Rohner married Margaret Emmeline Edmonds in 1862. At the time of his disappearance they were estranged and she evidently arrived in Hastings on the same afternoon of his disappearance.

The family apparently assumed that Dr. Rohner was no longer alive and he must have left them in straitened circumstances for the following letter, having already appeared in The Argus, was printed in the North East Ensign on 24th February, 1891:

“Sir. On behalf of the widow and family of the late Dr. C.W.Rohner I have made an appeal to the medical profession in particular and will thank you to take charge of any contributions which may be sent to you to allow acknowledgement to be made through the columns of your newspaper. Yours etc. S. Jacoby, Esplanade St. Kilda. Feb 14.”

Mrs. Rohner lived for almost 30 years after the disappearance of her husband. The personal columns of The Argus of 5th January, 1918 informed readers of her death:

“On 31st December, 1917 at 38 Lewisham Road, Windsor, Margaret E. relict of the late Dr. Charles William Rohner, aged 77 years. (Interred privately in the Boroondarra Cemetery, Kew, on 2nd January.)”

A similar notice appeared in the North East Ensign on 11th January, 1918 and mentioning that Mrs Rohner had been in indifferent health for some considerable time. It also mentioned that there were three surviving children; they would have been one son (Emmanuel) and two daughters (Hypatia and Corinna.)

Of the eight children , there are not a lot of descendants:

1. Charles Armin Rohner-born in Chiltern 1863 but died of typhoid in Shepparton in 1889. Never married.

2. William Aberlard Rohner-born in Chiltern 1865 and died in 1901. He was a watchmaker and the cause of his death was listed as “abscess on the brain.” The following notice appeared in The Argus on 11th May, 1901:

“Rohner – on 6th May at Cobram, William, dearly loved husband of Mary Rohner and second son of the late Dr. Rohner and Mrs. Rohner, St. Kilda, aged 37 years.”

William married Mary Jane Burke whose death, “… late of Cobram, aged 79 years…” was recorded in the Sunshine Advocate on 13 February, 1942. It states that she “…was the mother of Mr. Ray Rohner, well-known locally, and also Will and Nellie (Mrs. F. Bolton). Bill and Beryl Rohner and Keith Bolton are grandchildren.” As well as Keith, Nellie also had two other sons (Ian and Clifford) and a daughter (Nancy). William’s marriage to Mary Jane Bourke was not approved of by the Doctor as she was a local girl; this caused a rift between father and son!

Bill Rohner (a great-grandson of the Doctor) married Mavis King in 1953 and they had three children: Christine, Jeanette and Peter. There are two boys from Peter’s marriage, so the Rohner name continues. Bill and Mavis Rohner moved to Wahring in their retirement, close to Jeanette and her husband, Murray. Bill died in 2007 but Mavis, at 85, still plays the organ in the Uniting Church in Murchison. She and her grandson, David Robinson, have released a CD titled “Across the Years.”

3. Ferdinand Charles Rohner-born in Chiltern 1868 and died in Chiltern the following year. (Ferdinand was named after the Doctor’s only brother.)

4. Hypatia Irene Rohner-born in Chiltern 1869 and apparently came to Hastings with her father in 1888 as his housekeeper. She must have stayed on in Hastings for in 1891 she married John Henry Newton Jones, the son of a Hastings fisherman, Evan Gilbert Jones. Her husband was a missionary employed by the Reorganised Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints and they spent time in South Australia and New Zealand. They had no children but adopted a daughter (Phyllis Doran). Hypatia died at Ivanhoe in 1955. Anne Loughran of Maidstone is a granddaughter of William Jones, a younger brother of John, and recalls visiting “aunt ‘Patia” at Ivanhoe prior to her death in 1955. The mystery surrounding the disappearance of Hypatia’s father was never discussed; it would appear to have been a taboo subject! However Mrs. Loughran was able to shed some light on the adopted daughter of John and Hypatia Jones: it was believed within the family that she was the illegitimate daughter of Corinna who was apparently jilted as a young woman.

5. Corinna Delores Rohner-born in Chiltern 1875 and died in Fairfield in 1957. Did not marry.

6. Laura Beatrice Rohner-born in Hamilton 1877 and died in St. Kilda in 1916. Although she predeceased her mother, Laura married (William Thomas George Hallam) and had two daughters: Irene (who died at the age of 20) and Brenda (who married Richard Dunstan and had two children).

7. Emmanuel Candide Rohner-born in Bright 1879 and died in Elwood in 1940. He married Margaret Jane Anderson and they had one daughter (Gwendoline) who married (Harold Ernest Neill) and had a son (Barry Neill). Barry had a son and a daughter. Emmanuel married Maggie Jane Plowright after the death of his first wife. Emmanuel and Laura lived in close proximity and were confectioners in the St. Kilda area at one time. They were both fined for selling tobacco /cigarettes on a Sunday in 1915 – not long before Laura died. (Emmanuel would have only been 11 when his father disappeared).

8. Ania Mara-born in Chiltern 1883 and died soon afterwards.

For most of this information I am indebted to Jeanette Robinson, a great, great granddaughter of the Doctor.

A link with Australian literature

WHEN Dr. Rohner departed Chiltern in 1876 he sold his practice to Dr. Walter Lindsay Richardson.

WHEN Dr. Rohner departed Chiltern in 1876 he sold his practice to Dr. Walter Lindsay Richardson.

The Richardsons lived in “Lake View”, now owned by the National Trust, and although the family moved on after 18 months, the town made a lasting impression on their elder daughter, Ethel Florence.

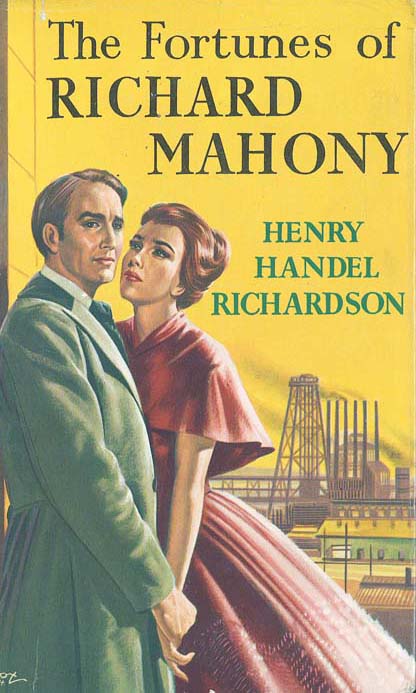

Writing under her pen name of Henry Handel Richardson, Ethel wrote a number of classic novels including “The Getting of Wisdom”, based on her experience as a boarder at PLC, and “Maurice Guest”, which was set in Leipzig where she studied at the Conservatorium.

Richardson’s best-known work, however, was “The Fortunes of Richard Mahoney” (pictured), a trilogy about the slow decline, owing to character flaws and an unnamed brain disease of a successful Australian physician and businessman, and the emotional/financial effect on his family. The central characters were based loosely on her own parents. It is understood that the town of Barambogie referred to by Richardson is in fact Chiltern and Dr. Rummel is drawn from her father’s predecessor, Dr. Rohner.

FOOTNOTE: As well as the information provided by Jeanette Robinson, the assistance given by Shirley Davies of the Hastings Western Port Historical Society is greatly appreciated. Special thanks to the Chiltern Athenaeum for the photographs.