The Royal Hotel, Mornington.

By Lance Hodgins

It was a publican’s/hotel keeper’s worst nightmare.

Over a hundred ruffians had stormed the hotel and were helping themselves to the delights of the bar and running amok throughout the halls and the rooms. Scavengers, vagabonds, picked scoundrels, well-known thieves – the very worst of the roughs of Melbourne had descended on the Schnapper Point Hotel (later to be known as the Royal) and Thomas Rennison was far from impressed.

It all started innocently enough. Late afternoon on Sunday August 18 1861, a steamer pulled into the Mornington jetty and within moments two men strode into the hotel. The one with fair hair and a more gentlemanly appearance introduced himself as Patrick Costello, newly elected member of parliament for the seat of North Melbourne, and requested to hire a committee room from 9am till the close of poll at 4pm the following day. No sooner had this been arranged when five men rushed into the hallway where they were met by Costello and ushered into a room.

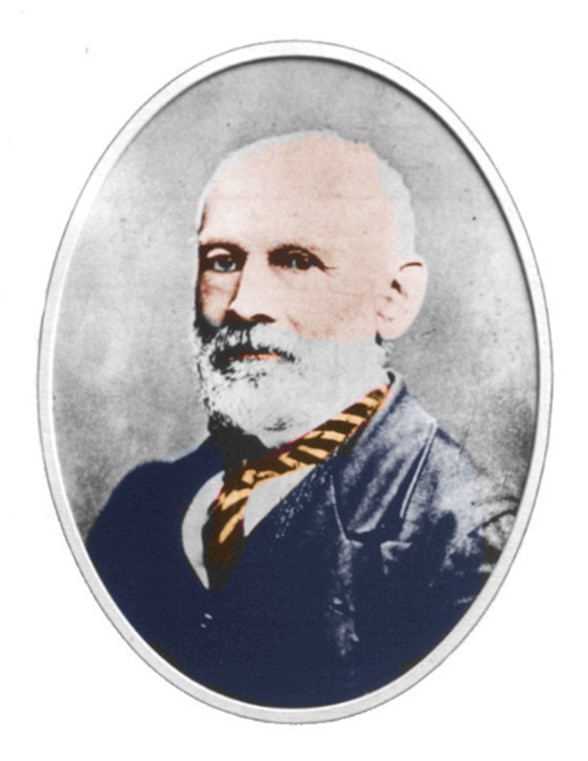

Patrick Costello

Costello emerged to request a carriage to take him to a friend’s place further along the coast. On his return about 8pm there was a large crowd from the steamer milling around in front of the hotel demanding supper and beds. Costello told them, “Go in first, boys, and get nobblers,” then followed them shouting, “These fellows must have drinks.”

The mob rushed in and took over the bar, not paying for their drinks and stealing dozens of bottles. After downing their ale, or whatever, they smashed the glasses against the wall. Rennison remonstrated with Costello who simply shrugged his shoulders and said, “They’re already in. You may as well make the most of it.”

Rennison continued to complain about the damage but was assured that all would be paid for in the morning. When Costello raised the matter of breakfast, Rennison told him that he “would not trust him four pence” without a written order, which was duly provided.

The purpose revealed

Costello then tapped the hotel keeper on the arm. “Old fellow, I want to have a word with you,” and drew him aside. “I want a few votes out of Balcombe’s nest,” he confided. “I care not what they cost. Can you procure me a good man or two in the neighbourhood?”

He then pulled out a huge roll of notes – possibly £60 ($60,000 in today’s money) – and asked Rennison if he could be trusted to lay it out judiciously. Rennison refused, saying that he had nothing to do with the election and he would have nothing to do with Costello’s money – apart from what he would be owed for damages.

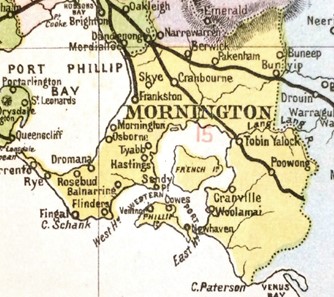

A Map of the Morninton District.

The Mornington district was a far-flung electorate with almost 1,000 potential voters and six polling places, two of which were on the peninsula: the Tanti Hotel at Schnapper Point (Mornington) and Scurfield’s Hotel at Dromana.

The contest was between Henry Chapman and Alexander Balcombe. Chapman had already served in the Irish-Catholic O’Shanassy government and was better known in the Dandenong region to the north, whereas the land-owning Balcombe was expected to be an overwhelming success among the voters of the peninsula, where he had made The Briars his home.

Elections had been unruly affairs, with voting often held in the only available public place – a hotel – and open to all sorts of alcoholic abuses. Five years earlier, the new Victorian Constitution had brought in a world first – the secret ballot – where names were checked off a roll and a card with the candidates’ names was marked and dropped in a box. 1861 would be the third State election but there were still loopholes in the system. A study of the electoral roll showed that there were sufficient numbers of absentee voters in Schnapper Point and Dromana who could be “personated” – the legal term for voting as someone else. It soon became clear to Rennison what Costello and his mob were up to.

For the present, however, they were simply becoming more unruly and conducting themselves in a drunken, disgraceful manner.

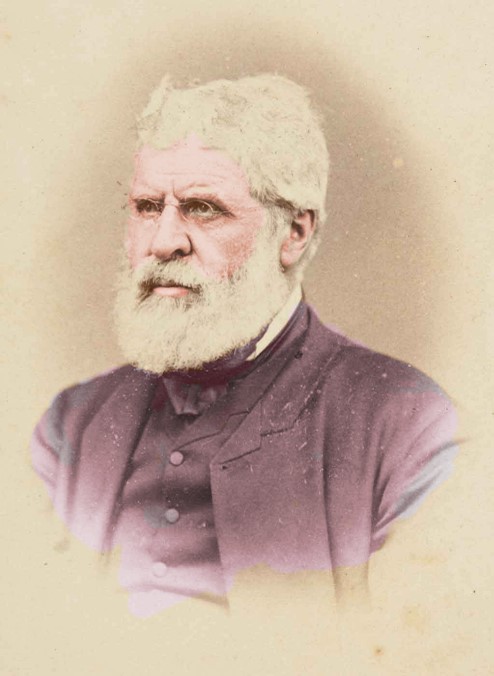

H. S. Chapman (left) & A. B. Balcombe

A one-eyed ruffian shouted offers of £5 for whoever drew “first blood” in the morning. When Rennison threatened to call the police Costello responded with, “By Jesus, they couldn’t be driven out by a regiment.” The hotel keeper, his wife and the servants spent all night standing guard.

The morning could not come soon enough. At daybreak, Costello muttered something about coming back to pay for the damage, and then drafted 46 of his men and boarded the steamer for Dromana. Rennison surveyed the damage. His recently renovated hotel had walls spattered with liquid, tablecloths and curtains rolled up as temporary bedding, and furniture in pieces. There were still bodies everywhere, sleeping off the night before.

Off to “work” at Dromana

When he reached Dromana, Costello called his men together and told them that they were about to personate voters. This drew a mixed reaction but the one-eyed Louis Frankel ferried the first boatload of eight ashore and landed them about half a mile from Scurfield’s Hotel. Costello helped them change their coats before thrusting them towards the polling booth. Some were reluctant and needed to be manhandled into the hotel.

Early Dromana at the foot of Arthurs Seat

Thomas Smith was only a few yards away and looked on in amazement. The bootmaker from Schnapper Point travelled frequently to Dromana and he knew most people in the district. He saw Costello walk a man from a room saying to him, “Now you must remember your name is Thomas Clancy, Point Nepean.” Smith knew this was a lie as he knew the real Clancy well. At the polling booth Costello had the man by the arm and thrust him inside.

Costello then brought in another man and told him to remember the name Hugh Fox. Fox happened to be a personal friend of Smith, who knew that he was “across the Murray” in Wagga.

A third man was escorted to the polling booth door and told to be William Jones. The travelling boot maker had known Jones for five years and, again, knew that this man was not him.

Later in the morning, the Returning Officer had proof of the scam when the real “Clancy” and “Jones” finally came in to vote.

The personations continued, however, until the bootmaker Smith and a friend, Boag, confronted Costello on the veranda of Scurfield’s.

“What do you mean by robbing honest men of their votes?” they demanded.

Costello drew them aside. “Now, look here, my friends. Don’t make a noise about this. I am the member for North Melbourne. You want a jetty at Dromana and I will secure your jetty. I can do more good for you than ever old Balcombe could do.”

“I don’t trust you,” replied Smith. “You are rotten at heart.”

Other things failed to run smoothly for Costello, sometimes from surprising sources. John Anglam was a hawker, an unruly character, a former convict, and a simple man who knew nothing at all about politics. He was handed a name and told to go and vote.

“I’ll be damned if I will,” was the reply. At that, Costello caught him by the shoulder, dragged him to the committee room and dressed him down.

Jeremiah Rigby and his mate Davy Leary had left the boat and were nearing the hotel polling booth. They were given names by Costello, but they objected and returned to the boat where they were met by a dozen others who had also refused to vote.

Costello arrived back at the steamer and stormed on board.

“You are a bloody lot of duffers,” he yelled at the group. “What did you come here for then?”

Some of the men answered that they had come to canvass.

Costello was ropeable. “You are a bloody nice lot of electioneering men.” And then in a more threatening tone, “I will remember who you are.”

“What about our pay?” asked one brave soul.

“You will be settled up at the Spanish Hotel tomorrow night. But mind you, any man who didn’t vote will not be getting paid at all.”

At that, Costello ordered the steamer back to Schnapper Point.

Meanwhile at Schnapper Point

About fifty “voters” had stayed on at the Point. Timothy Murray had been left in charge, with Frank Ryan and John Nathan as his offsiders. Murray’s main qualification for the job seemed to be that, of the three, he had the longest list of arrests for drunkenness and street fighting.

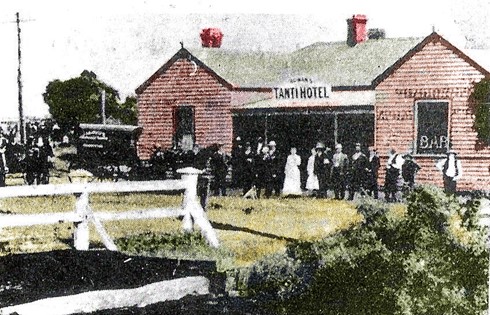

They roused the weary bodies from Rennison’s hotel and directed them along the track to the polling booth at the Tanti Hotel, a mile inland on the main road.

Voting was in full swing by 9am and personations were the order of the day. Ryan and Murray met “their men” at a distance from the polling booth. They were armed with the electoral roll, containing names and qualifications of the voters. Certain names were marked with a “D” which meant they were “out of the country” – or, more accurately, “dead ‘uns”.

The Tanti Hotel, Schnapper Point, a few years on.

Sixty suits of clothing had been brought down on the steamer by Frankel, the insolvent who ran an old clothes shop near the Eastern Market. These were used by Ryan and Murray as they sought to effectively disguise the voters, particularly those who would go in several times.

By early afternoon about 25 personators had cast their votes. One man even voted four times before he finally said, “Enough is enough.”

William Grover, a well-respected local builder and future JP and Shire president, had observed Ryan and Murray as they approached each imposter while continually consulting and making marks on their list. Grover rushed inside the polling booth to alert the scrutineers.

The next “voter” was James Barry, a simpleton and, like many of the others, he had spent time in gaol for drunkenness and fighting. He was pushed into the polling booth and offered his name as James Burke #21 of the Schnapper Point Road. When pressed for his qualification, he became confused and blurted out “in Little Bourke Street”. Ryan stood at the door repeatedly hissing “Freehold, Frankston” – which was the real Burke’s qualification to vote. When Barry was asked to swear his identity, the flustered man turned and ran off.

A similar incident occurred when another man was brought up and gave the name of James Mason. When asked for his qualification, he correctly answered “Freehold in Osborne” but the scrutineer knew the real Mason and accused the man as an imposter, who immediately fled the room. There were eight further attempts to personate Mr Mason – all of them, of course, met the same failed result.

More frustrating for Ryan and Murray was the sheer unwillingness of some of their men to be involved. Frederick Green, a street brawling cab driver of North Melbourne, when offered a name, simply refused to vote, and relented only when told he wouldn’t get paid. The name given was an Irish one but, since Green had Jewish features, he was promptly given another one – Moses Moss. Green had them write it on a piece of paper, which he kept and later produced in court. He and his mates then walked straight past the polling place and failed to vote.

Several others also refused to vote, and by early afternoon Murray had given in. “Damn this lot. I’m sick of them,” he uttered as he lay down on the grass near the Tanti. Costello and the others would be back from Dromana soon.

On their arrival, Costello was first ashore and proudly announced that all his men had voted – which was quite untrue. When told that only about twenty had done so at Mornington, he exploded with rage. “You’re a lot of muffs. I did all mine and if I had yours I’d have polled them too.”

He turned to John Nathan and told him that even his brother, Abraham, had voted.

“Well, he must have been either drunk or a fool,” was the retort.

“Oh he’s all right,” replied Costello. “I left him in good hands.”

Those “good hands” were, in fact, those of the local constable. Abraham had voted for Samuel Barton and then Edward Russell, and was promptly arrested. Several days later he appeared in Mornington police court and pleaded guilty to the charge of personation.

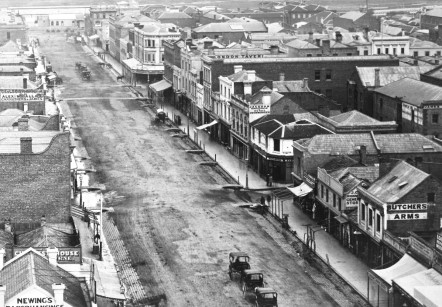

Elizabeth Street in the 1860’s.

The slippery paymasters

The steamer returned to Melbourne and by Tuesday evening the bar of the Spanish Hotel was full and the crowd spilled out onto Elizabeth Street. They were there to collect their “wages”, but Costello was nowhere to be seen. Nathan, who had originally rounded up the mob from their pubs and hovels on a promise of £2 (or $2,000 in today’s money), was left to soothe the crowd and promise that all would be settled the following night at Costello’s hotel.

“What a mess we have made of it,” Nathan said to Costello the next day when he entered his Travellers’ Home Hotel. They sat at a table and received a steady stream of “workers”, paying some but refusing to pay those who had not voted. When one presented a falsified voting card as proof, Costello politely excused himself – and disappeared out the back door.

In a strange twist a few days later, Costello found himself in the District Court being sued by 24 of his ruffians for work done – even Jonathan Nathan claimed £20 “for services rendered at Mornington”. The case was thrown out on the grounds that canvassing debts were not legally reclaimable.

Costello had another minor victory when Rennison sought payment of £45 for damage, inconvenience, accommodation and 116 breakfasts at his hotel. The County Court ruled that Costello was not responsible for the men’s unruly behaviour and that only the written breakfast contract was enforceable. Rennison was awarded only 16 guineas.

Costello’s run of luck lasted long enough for him to see the election results. As predicted, Balcombe led in both Schnapper Point and Dromana, but Chapman took the parliamentary seat by just 21 votes: 336 to 315.

Costello’s hotel “Travellers’ Home Hotel”, Swanston Street, 1860’s.

Costello heads to trial

Patrick Costello, Frank Ryan, Louis Frankel and Timothy Murray appeared in the District Police Court for committal to trial for combining and conspiring together to induce certain persons to personate voters. All four pleaded not guilty and said nothing. They were granted bail and ordered to stand trial in the Supreme Court two weeks later.

In the meantime, Victoria’s third parliament had commenced its sittings and many people were annoyed that Costello had the effrontery to take his seat with criminal charges hanging over his head. He was sworn in as a law maker under the noses of the very two Judges before whom he would shortly appear in a different capacity.

The trial was moved to Ballarat. No fewer than 15 jurors were challenged, and the defence tried unsuccessfully to argue that personation was not a specified criminal offence under the Electoral Act. The defence called no witnesses and presented no alibis. A crowded courtroom heard up to 40 witnesses for the prosecution and the trial lasted seven hours.

The jury took only half an hour to find all four guilty of inducing men to answer questions falsely, and then guilty on the general issue of personation. The defendants sentenced soon after: Costello was seen clearly as the ringleader and received 12 months imprisonment, and the others six months.

Old Ballarat Court House.

Some important questions remained

(i) Who was really behind this whole sorry mess? Was it solely Costello, who had already won himself a seat in Parliament? Or was he backed by a secret political pressure group called the Victorian Association? This was a group akin to today’s “GetUp” which was developing a murky reputation for political interference in the days before a party system. Or was the ambitious Chapman behind it?

(ii) Given the questionable validity of the voting, should there have been a new poll taken for Mornington? Balcombe was urged by his supporters to protest the result – but he politely declined. Chapman defiantly took his seat in Parliament but resigned mid-term to become a judge in the Supreme Court.

(iii) What would happen to Costello? In March 1862, after serving only half of his sentence, he was released from prison following a petition signed by 37 members of parliament. Of course, this met with widespread criticism.

A year later he was declared insolvent after a long and messy case. Costello, however, was a man of resilience and after two decades as a contractor he once again owned property in the city. Another insolvency followed and, on his release in 1891, he was elected to North Melbourne Council and in the following year became their mayor.

Costello died in 1896 and was buried in Melbourne General Cemetery, leaving an estate of £998 – almost $1 million in today’s money.

Post script

Just over a century later, two of Patrick Costello’s great-great grandsons were making names for themselves in public life. Tim Costello, a Baptist minister, was the CEO of World Vision Australia and his younger brother Peter was Australia’s longest serving Federal treasurer in the Howard government.