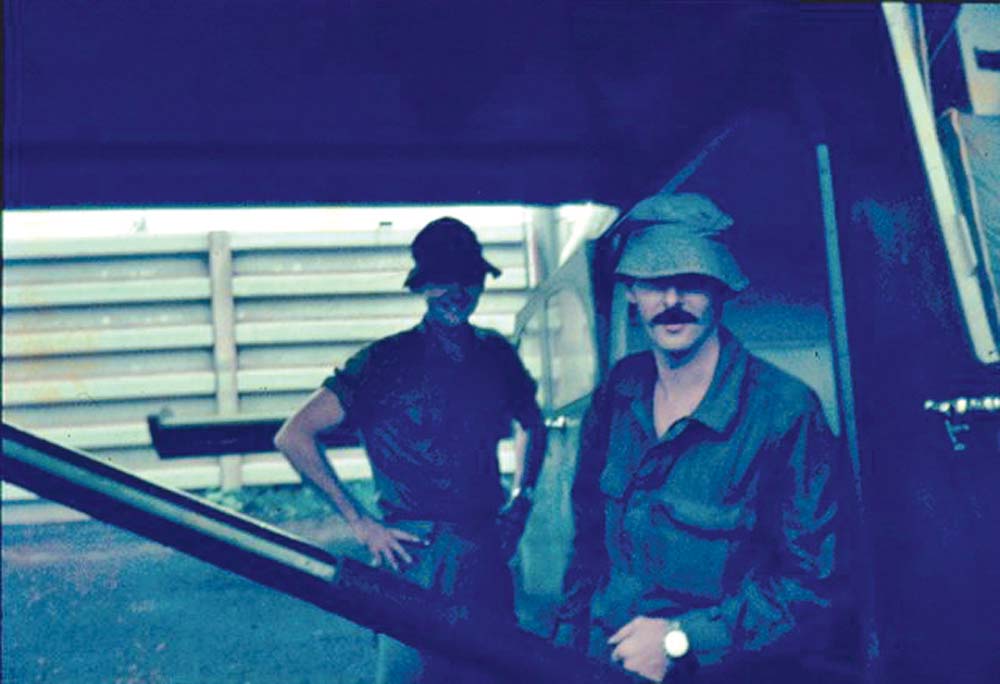

By Cameron McCullough Photos Gary Sissons and supplied

Paul Stock has had a long wait for recognition for his Vietnam War service.

The Somerville resident, along with other members of the highly secretive 547 Signal Troop, attended an award presentation on 27 March 2019 at Borneo Barracks in Cabarlah, Queensland, where they were presented with the “Republic of Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with Gold Palm Unit Citation”, an award presented by the Australian government, in the name of the now defunct Republic of Vietnam government.

“It has been 50 years, which is a long time to wait for recognition,” said Paul.

“In fact, due to the secret nature of what we did in Vietnam, many of the men I served with have never spoken about their service. Many had parents who died not knowing what their sons actually did at war.”

Paul joined the Australian Army in 1965. “I did it in anticipation of being called up. I thought if I joined up voluntarily, I’d have more options as to what I could do in the army.”

Paul, the fifth of eight children, was the first member of his family to join the armed forces and recalls a father who was, at worst, ambivalent or at best, quietly proud, and a mum who didn’t want her son to leave.

“It was the first time I ever saw her cry”.

Paul was sent to Kapooka, near Wagga, for 12 weeks of recruit training, before being sent to the School of Signals at Balcombe to basic signals training.

“I was aptitude tested for high-speed morse code. We received further training in Sydney, then were sent on to Borneo Barracks at Cabarlah for Operator Signals Training”.

Meanwhile, as the Vietnam War intensified, the commitment had been made around May 1966 to add a signals intelligence component to the growing Australian presence in Vietnam. The 547 Sig Troop was raised and, in June 1966, found itself in Vietnam.

“547 Sig Troop was fresh on the ground and dealing with very primitive conditions. They had old World War Two era equipment, based in tents, and found themselves having to risk life and limb rigging 100 metre antennas up masts,” said Paul.

“They were intercepting enemy radio transmissions, and with the assistance of the US ARDF (airborne radio direction finding), they were able to estimate the direction of movement of Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces moving towards the Australian taskforce at Nui Dat in August 1966.

“The intelligence was not given the credibility it should have been by the taskforce headquarters. On August 17, the taskforce was heavily mortared by Viet Cong. As a result, elements of 6 Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR) were deployed to seek out enemy activity. On the afternoon of 18 August 1966, D Company came under massive sustained attack from in excess of 2500 enemy infantry men.

“D Company numbered in the order of 100 members. That was what came to be known as the battle of Long Tan.”

Eighteen Australians were killed in the battle, and 24 wounded.

“547 Sig Troop was left disappointed that the credible intelligence we provided was not seen to be acted upon as well as it could have or should have been,” said Paul. “In the future, we were taken with more credibility. After that time, not many commanders went into the field unless they tapped into the 547 Sig Troop’s intelligence source.”

Paul was posted to a communications station in Singapore from 1968 – 1970. Between February and June 1969, he was detached for his first stint with 547 Sig Troop.

“During my first stint, living and working conditions were fairly primitive with no paths (no fun during the wet!) and accommodated in large, World War Two era canvas tents. I was employed during those months as in intercept operator. It is worth noting that during that time enemy activity was still fairly high in Phuoc Tuy, the province for which Australia had responsibility. During those months, several rocket attacks were carried out on the Australian taskforce on Nui Dat. The only casualty was the rubbish dump.”

It was a relatively uneventful tour for Paul, who was “grateful to get out of the stinking, enveloping heat of Vietnam.”

Paul went back to Singapore to complete his posting. There, he met his wife, Sue, married, and returned to Australia in February 1970.

“It must have been tough on her. I basically left her with my parents and headed back to Vietnam in May 1970,” said Paul.

May 1970 to April 1971 was to be Paul’s longer tour. Once back in Vietnam, he did two weeks of familiarisation on the sets to get a feel for the communication methods of the enemy. Then went straight into the flying team, carrying out ARDF missions against enemy radio transmitters.

“The skill of the Australian intercept operators in Vietnam cannot be overstated,” said Paul.

“Within days of arriving in country, to be working in hot, humid conditions often using World War Two era radio sets, they had thrust upon them the responsibility for accurate intercept and recording of all enemy radio transmissions.

“Their skill at recognising not only the radio transmitters assigned to particular enemy units, but also the physical sending characteristics of individual enemy radio operators was nothing short of astounding.”

Paul recalls one time when one of the enemy transmitters that had been silent for some time suddenly burst to life.

“Chau Duc is up,” was yelled by the intercept radio operator. Chau Duc being the name of a local Viet Cong battalion.

Paul was on ARDF duty that morning and was sent out in a Pilatus Turbo Porter PC6 to try and locate the radio transmitter.

Making numerous runs across the landscape, Paul and his team managed to pin-point the enemy radio transmitter in a swampy area known as the Rung Sat.

“Once we had a fix on the transmitter, it was hurriedly taken to Task Force by our Operations Officers, but was not well received by the Commanding Officer of the Australian Battalion which was operating in the same area as the fix. He doubted the accuracy of the information we provided,” said Paul.

“He was ‘encouraged’ to go out there to see for himself if the enemy was there. His helicopter was fired on by enemy troops, shot down, and he copped a bullet in the left buttock for his trouble“.

Paul returned to Australia in 1970, served in Singapore between 1971 and 1974, and eventually left the army in 1985.

After that, Paul worked at Dookie Agricultural College, and then in various businesses, before retirement.

Paul stays in touch with what is now a reducing number of his 547 Sig Troop colleagues.

“We figure that of the 280 plus personnel that served in Vietnam, 70 or 80 have passed away. Many of the remaining attend an annual reunion each year in Queensland.”

As for going back to Vietnam, Paul hasn’t done it yet, but is not against the idea.

“Maybe when my wife retires, we will,” said Paul.

“When we were stationed at Nui Dat, the makeshift toilets were literally a trench cut unto the ground with concrete pad over the top. After it was no longer required, fresh concrete was poured over it, and one of the 547 Sig Troop wags scratched into the still wet concrete ‘Here lie the remains of 180 members of 547 Sig Troop who served in Vietnam between 1966 to 1970’. I think that would be worth going over to see.”

Although they have received the “Republic of Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with Palm Unit Citation”, the troop has never received formal recognition for their covert work from the Australian government.

“The Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal does not consider 547 Sig Troop’s outstanding achievements in South Vietnam worthy of a meritorious conduct award,” said Paul.

That has made life difficult for those who served, and created stress not only on the soldiers, but also on their families.

Perhaps the last word should go to an unknown officer who once told a batch of signal corps recruits:

“Not only do you not exist, you never will have existed. You will remain for always unknown and unacknowledged. There will be no awards, no glory. There will be no medals for this unit.”

Let’s hope that the members of the 547 Sig Troop, and our own Paul Stock, get the recognition they deserve.