‘Take your school elsewhere … we won’t be sorry’

By Lance Hodgins

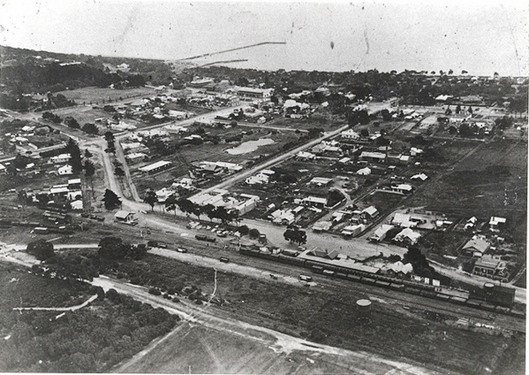

A magnificent structure – the original Frankston High School – stood for almost a century until it was demolished late last year.

One hundred years ago, the people of Frankston fought the government to have it established in their town. They also fought each other as to where it would be built.

This is the story of that struggle.

In the years immediately after the Great War, the question on most young teenagers’ lips was, “What am I going to do after school?”

To most, ‘school’ meant primary school – which generally took most of them on to Grade 8 and then into a shop, factory or back home on to the farm.

There were schools which prepared children for further studies, and there was no shortage of them – over 50 registered secondary schools south of the Yarra. But these religious or private schools were expensive and out of the reach of parents of moderate circumstances.

In 1922, there were only five government high schools in Melbourne and not one of these was south of the Yarra. The lack of community pressure came from parents being “reluctant to bump up against established interests.”

Dandenong had been granted a high school in 1919 and it was in a situation similar to Frankston – an outer town on the edge of an extensive farming district. Opportunities for the local kids remained extremely limited. It was not difficult to argue that the Peninsula needed a high school.

The first moves

The local Progress Association began to agitate. In July 1920 they encouraged Council to ask the Education Department what was needed, the answer being a local contribution of £1,000 and a suitable site of at least eight acres. They were also informed that only six new schools would be built each year and that there had already been 21 applicants.

At first they had hoped for a higher elementary school adjacent to Frankston Primary School. By the end of 1921, however, the Chief Inspector of Secondary Schools, Martin Hansen was in Frankston advising the Council and School delegates to go with his own preferred option – a separate High School. He had inspected a six acre site on Hastings Road, which he considered too far from the railway station, and he preferred the ten acre cricket reserve in Cranbourne Road.

A public meeting was called and Councillor Chas Gray stated that, although he was opposed to using reserves for other purposes, the school would occupy only the idle portion of that land. The only speaker to totally oppose a school on the cricket reserve was long-term resident, Joseph McComb. As a young man he had cleared the site and felt that it was too valuable to just give away. His was the one dissenting vote when the meeting elected to provide the site for a school.

One hundred students would be required – but nothing had been done to gather names! Once again the Frankston Progress Association stepped in and drove around the Peninsula to gather the signatures of potential students.

Council then faced another serious obstacle: money. The start-up amount required by the Education Department was raised to £1,500 and the neighbouring Shires of Flinders, Mornington, Cranbourne and Carrum were not keen to contribute. The Shire of Frankston and Hastings was left to struggle with the prospect of striking a special rate for a couple of years.

When Council forwarded the names and £100 deposit to the Education Department, they did not receive the answer they were looking for. The Department announced that it was still not able to guarantee Frankston that they would secure a high school. Frankston might have the money and the children – but there remained one key question to be settled: where would it be located?

The cricket ground site was far from done and dusted. The Education Department now maintained that it would require more land than the two acres on offer and would settle for nothing less than the entire ten acres of the cricket reserve. Community opposition became louder.

Furthermore, if it was a permanent recreation reserve then it would take an Act of Parliament to allow it to be used for other purposes. Council was relieved when they received legal advice that the reserve was in fact a temporary one and would need permission from only the Council and the Cricket Club. The cricketers agreed (11 to 2) to be relocated to an unused portion of Frankston Park, so the rest would depend on Council.

The deadline for parliamentary estimates was looming on June 30 and Council had to act quickly. With only one abstention, they decided to allow the whole of the Cranbourne Road Reserve to be taken over by the Education Department. There had been no time for public debate beforehand, so Council was forced to hold a public meeting a few days later to seek endorsement of their action.

A rowdy public meeting

The meeting on Friday 14 July 1922 was a lively gathering of over 300 people. The Chairman began by pointing out that Frankston was not short of reserves and that this one was used for only seven cricket games a year and had been leased for cattle grazing for the past twenty three years. He had heard that there had been “a fairly big petition” to save the cricket reserve, at which point Joseph McComb stood up in the body of the hall and waved a roll of paper threateningly at the platform. He was drowned out and eventually persuaded to regain his seat.

Local undertaker and landowner, Hec Gamble seconded the motion as the reserve, apart from a few games of cricket, was used only as “a camp ground for contractors and swagmen.” He questioned the validity of the McComb petition, claiming that people had been misled into thinking that there were alternative sites.

At this, McComb jumped to his feet and approached the platform demanding an explanation, but was returned to his seat. Minutes later he again approached the platform and read a resolution which “condemned the Council for its breach of trust in alienating the only recreational ground in Frankston”. This caused widespread laughter and uproar, and it was ruled out of order.

“What about the children who don’t go to high school?” he shouted. “Will they be barred from using the reserve? I am here as the champion of the people’s rights.”

McComb continued, bringing derisive yells and much shouting. “The chairman has made a lot of statements which were only bluff.”

Pointing at the councillors seated on the platform he added, “Councillors should remember that they are only the servants of the public – we stand on a higher level than you.”

As if to support this sentiment, Cr William Oates then rose and explained why he had been the only councillor to oppose using the cricket reserve for a school. When the Department had changed its mind and wanted all of the land, he felt that this was over the top. He was in favour of the school being built there, but wanted the reserve to be used conjointly by the school and the public.

Mr McComb again made his way to the platform and presented a copy of his petition of 276 signatories “to save the cricket reserve”. He called for a referendum which was not supported.

Councillor Gray warned that since the trustees of the cricket reserve were all dead, the Lands Department just might step in and take the reserve from them. The people needed to wake up and make the first move. The meeting then voted overwhelmingly to support Council’s intention to make the cricket reserve available for building a high school. Only 15 people stood up in opposition, and the motion was carried to loud and prolonged applause. The 8 o’clock meeting had lasted until nearly midnight.

Within days, a petition of 600 signatories in support of the school emerged. It contained many people who removed their names from McComb’s original one, claiming that they had been unaware that an objection to a school at the cricket reserve might mean losing the school altogether.

Both petitions ended up on the desk of the Minister for Lands, who listened patiently to each deputation and then promised to discuss matters with the Education Minister.

Council elections fought on the school issue

In August 1922 the school matter became a local election issue when the Standard newspaper owner Crawford Young opposed Cr Oates for his Council seat in the Frankston Riding.

At his election rally, Young reminded the audience that the Council had dragged its heels for two years, and accused Cr Oates of being the problem all along. He claimed that Oates had attended meetings as an observer and then spoken in opposition to the high school being on the cricket reserve.

“For someone who campaigned that he was in favour of a high school, he was adopting a very peculiar method of attaining this,” Young concluded.

A few days later at his own rally, Cr Oates explained that as there had been no government response to the petitions he had asked the School Committee to look into alternative sites “for the Minister”.

His election opponent, Crawford Young, arose from the audience and asked, “Why are these sites being put forward again? They have already been rejected by the Education Department. On whose authority are you taking these alternatives to the Minister?”

Despite the pertinence of these questions, Oates’ reputation saw him re-elected to Council and his supporters became emboldened. One enthusiastic outburst in the local press came from Joseph McComb who believed that his man Oates had been unfairly pilloried over the issue. To the threat of losing the school altogether, he wrote that it would be “better to let the high school go than surrender our recreation ground. Let Chelsea, or Carrum or Mordialloc get it and, if they do, they will have the taxation and we will have the benefit. Ours will be the gain while others will have the pain”.

This only heightened public reaction. Many felt that Mr McComb was in effect saying “put your school where Oates and I want it – otherwise take it somewhere else – we won’t be sorry.”

“You have not been worthy of yourselves.”

In December 1922 the Chief Inspector of Secondary Schools, Mr Hansen, re-visited Frankston and told his audience that he was not happy to be there.

“You have been disunited over small matters and have let me down,” he told them. “You have not been worthy of yourselves.”

He reminded them that the grant for the school had now lapsed and it would be difficult to recover it. He promised to continue to fight for their cause – but only if they could agree.

Cr Oates immediately went on the counterattack. He pointed out that the public had offered two acres but the Department had “grabbed the lot” whilst rejecting an alternative site which he personally considered to be a splendid one. He maintained that reserves were necessary and if it had not been for the “old heads” there would be none.

Joseph McComb added, “I’ve been here for almost 70 years and helped clear the reserve. We won’t give it up.”

From the chair, Cr Gray snapped back. “I don’t care if you have been here for a million years or if you landed in Noah’s Ark. The reserve is only a temporary one, and should be made available for educational purposes.’

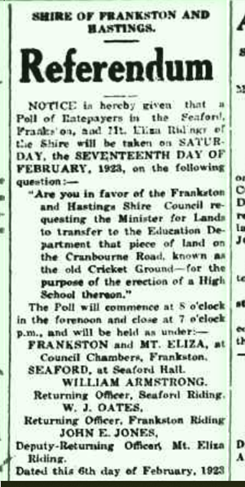

Putting it to the people – a Referendum

The meeting then voted overwhelmingly to conduct a referendum on the matter.

When Joseph McComb tried to have the vote declared illegal, Cr Gray observed: “If one man in the community can prevent progress in the face of the rest of the people, it is time the law was amended.”

The referendum took place on Saturday 17 February 1923. The YES vote won by 642 to 82.

The large crowd gathered outside the Shire Hall burst into wild cheering and the results were flashed onto the screen at the Frankston Pictures to several minutes of lusty applause.

Inaction and growing tensions

Despite this clear statement of support, little happened over the next six months as the government seemed to drag its heels, despite receiving several deputations seeking progress. People became even more anxious when they spotted the Minister of Lands inspecting sites for a new school in the Mordialloc area.

Finally a definitive statement came from Minister for Education Sir Alexander Peacock. He favoured a school on three acres with the rest governed by a committee.

Chief Inspector Hansen said that his Department was totally opposed to this and that he would be exerting his influence on the Minister to reverse his decision. The Education Department and its Minister were obviously at loggerheads and, in the weeks that followed, Hansen and Peacock were in frequent “consultation”.

The outcome was to be announced by Minister Peacock on Thursday January 24 1924.

It was almost a year since the referendum and a large body of people gathered at the Old Cricket Reserve. The official party was welcomed at the Council Chambers just before noon and immediately adjourned to the reserve.

Minister Peacock listened to speakers on both sides and then made his announcement: this was to be the site for the new school to be erected on three acres, and the scholars would have use of the other seven acres as playgrounds when not wanted by the public. Specifications would be drawn up and tenders let for its construction. The news was greeted with much cheering and hat waving.

Furthermore, Frankston’s high school would be opened for business in temporary accommodation in the old Masonic Hall in a matter of weeks.

And so, Frankston High School was officially opened on Tuesday 12 February 1924 – just six days before Mordialloc-Carrum High School. The new headmaster, R E Chapman, explained to the seventy new pupils seated on the floor of the rented accommodation that this was an informal occasion as they were still short of furniture and other teaching requirements.

Amongst the many guest speakers was Joseph McComb who told the students of his own early school days and pointed out the educational opportunities that were available to them today. The ceremony concluded with three hearty cheers from the scholars – and brought a tear to his eye.

Footnote:

Lance Hodgins is a proud former student of FHS (1954-59).

This is a chapter from “Tiffs over time”, a collection of arguments from earlier times on the Mornington Peninsula. Copies are available from the author for $20 plus postage (if necessary).

Contact Lance on 0427 160 892.