By Peter McCullough

If a poll was taken to determine Frankston’s favourite son, author Don Charlwood would have to be a strong contender. The fact that the café at the Frankston Library is called the ‘Charlwood Café’ would tend to support that view. However his family tree contains at least two other members who made significant contributions in their respective fields: his grandfather (John Cameron) was something of an entrepreneur in the early days of Frankston, and an uncle (John Alexander ‘Joker’ Cameron) served as a Farrier Sergeant in the Boer War and on return played VFL football with South Melbourne. Their stories were just too compelling to ignore so the Don Charlwood story starts with a brief pen portrait of these two ancestors.

***

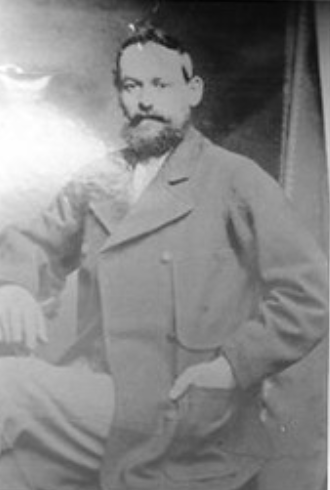

John Cameron

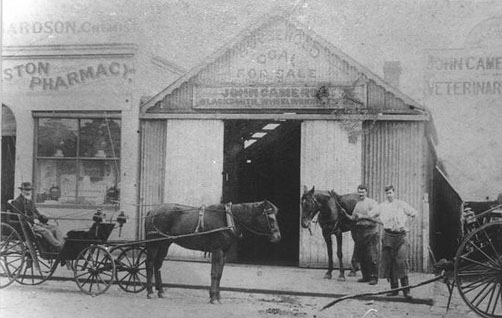

“Veterinary surgeon, coach builder, implement maker, blacksmith, trimmer, painter.” So ran the advertisement in the first Standard newspaper on 5 October, 1889. It showed that the early community of Frankston had to be ready to tackle anything.

John Cameron, son of John and Mary Cameron, was born in 1843 in a small Scottish highland village below Ben Nevis. He was still a very young boy when his father died and his mother remarried; with her new husband and three children she set sail for Australia. They arrived in Melbourne in 1850 and were met by Angus Cameron, John’s uncle, who had a farm at Moonee Ponds. They were also welcomed by another uncle, Donald Cameron, who was farming and horse breeding on 650 acres at Craigieburn.

When he arrived in Melbourne John could only speak Gaelic. At that time there were many Gaelic-speaking settlers in the colony. With the formation of the Presbytery of Melbourne in 1842 concern was expressed for the welfare of these groups, and the Free Presbyterian Church opened the Free Presbyterian Chalmers Academy. John was sent to school there and he came proficient in the ‘Sassenach’ tongue (English), although he always spoke with a strong Scottish accent.

On 26 January, 1864, aged 21, John bought 39.5 acres at Craigieburn, next to his uncle. His neighbour on the other side was John Williamson whose brother-in-law was John Davey, an early pioneer settler of Frankston. John Cameron was told that there was an opening for a blacksmith in Frankston, and he subsequently took over the building and business from the existing blacksmith, Robin Thomson. He later married Annie Warden from Liverpool and they had three sons and five daughters.

In 1861 Cobb and Co. had started a service between Brighton and Mornington with a stop-over to change horses in Frankston; the cost was six shillings for one way. John Cameron looked after the shoeing of these horses, plus those of a daily coach which ran from Hastings to Frankston to catch the ferry to Melbourne. As all the roads on the peninsula at that time met in Frankston, John had a very good business going; he had just arrived in the town when the upsurge in traffic took place. In 1882 he built new premises and a new house on Bay Street (Nepean Highway) which he called ‘Ben Nevis’. By 1889 he had opened his coach-building premises and was employing eight to twelve men.

In the first five years of his business in Frankston the Licensing Court of Mornington granted a large number of licences, many of them to the Frankston Fish Company, for the use of road vehicles. The maintenance of these vehicles and many more ensured that John Cameron was always a busy man.

Spending many years looking after horses and being called on to undertake veterinary tasks, John Cameron decided to become a qualified veterinarian. He was fully qualified by 1889 and thus became Frankston’s first vet.

A decade later, in 1899, he died at his home ‘Ben Nevis’ at the early age of 56. First his widow, Annie, and then his second son, Hugh, carried on the Frankston Coach Factory until the arrival of the motor car. Hugh then became the first man in Frankston to advertise as ‘motor mechanic’.

John Alexander Cameron

When the war broke out in South Africa the third son of John and Annie, John Junior, known universally as ‘Joker’, was working as a blacksmith with his brother, Hugh. Although only 17, he was convinced by an overly-patriotic older sister that he should put his age up to 18 and enlist. While his place was obviously at home with his brother, keeping the family business alive, ‘Joker’, an outstanding physical specimen, responded to his sister’s challenge.

“Selection for the 4th Victorian Imperial Bushmen was highly competitive; only 750 men were needed; 4,000 applied in a matter of days. As Australia was at a high point of intoxication with Empire, the response in other capital cities was much the same. A stringent medical examination was followed by riding tests over a half-mile course of jumps set up in the Melbourne Domain; thousands went there each day to watch. Musketry tests followed at the Williamstown rifle range. A high level of bushmanship was demanded. The tests whittled the 4,000 to 853 all of whom entered camp at the Langwarrin military reserve near Frankston.” Charlwood, Don “Marching as to War”, Hudson, Hawthorn, 1990, Page 28.

On 1 May, 1900 Cameron sailed as a member of the Bushmen and subsequently served as a farrier in Rhodesia, Transvaal and Cape Colony, attaining the rank of Farrier/Sergeant. His duties were not limited to blacksmithing, however. “In South Africa, ‘Joker’ seems to have acted in typically Australian fashion. Since the government had economised by providing inferior saddles, he appropriated a better one from the horse of an English officer. And from somewhere he acquired a Boer pony. Thus equipped he went into action. The Boers were by then falling back on to their farmlands, often using homesteads as sniper posts. The 4th Victorian Imperial Bushmen found themselves required to burn the houses and crops of a people very much like themselves and to lead their families away to concentration camps. ‘Joker’ was revulsed.” Ibid, Page 29.

According to family folk lore, his disgust was such that he dropped his uniform into the sea as soon as the ship entered Port Phillip Bay and he flung his medals into Kananook Creek. He swore that he would never go to war again and consequently when war broke out in 1914 ‘Joker’ resisted any pressure to enlist.

On his return from South Africa John Cameron resumed playing Australian Rules football with Frankston before going on to play with South Melbourne between 1903-1911. He played 117 games and kicked 43 goals for the Swans. The ‘Encyclopedia of League Footballers’ by Jim Main and Russell Holmesby states: “A follower/defender, Cameron was a cool and clever ball player. He was a sure kick and could give and take hard knocks and knew every trick in the book. Cameron once told a teammate to stagger around and appear to be concussed after an incident to avoid being reported. The antic failed. Cameron played in South’s 1909 premiership side.” (Page 51, 1992 edition) In fact, the Swans defeated Carlton by two points with ‘Joker’ Cameron listed as one of the best players.

When football resumed on the Mornington Peninsula after World War One, ‘Joker’ Cameron was coaxed out of retirement even though he was 38 years old. He soon became one of Frankston’s best players again and was a member of their 1919 premiership team. He played spasmodically over the next few years, making his last appearance in 1922 as a 41 year old. ‘Joker’ Cameron became vice-president of Frankston Football Club and was a league delegate. In 2008, he was named in the MPFL Team of the Century.

By 1928 Cameron had obviously mellowed for he was successful in his application for a Soldier Settlement block at Morkalla in the north-west corner of the Mallee. He farmed there until his death in 1941.

Donald Ernest Cameron Charlwood

Don Charlwood was born in Hawthorn on 6 September, 1915. His mother, Emily, was the youngest daughter of John and Annie Cameron; accordingly, the family moved to Frankston when Don was eight and it was there that he completed his schooling in 1932.

In 1929 Don’s history teacher at Frankston High School asked him to write a history of the town. His mother, who had grown up in Frankston, drew up a list of senior residents of the town and he set off to interview them. The resulting oral history led to an award on Speech Day and it was published in installments in the Frankston Standard. Don Charlwood, just 14, was already investing his imagination in the Frankston of that era and even today his effort is a source frequently turned to by writers of local history.

As his school days drew to a close Charlwood decided that he wanted to be a writer and even approached Keith Murdoch who lived nearby on his property Cruden Farm. Only the distant possibility of a job as a messenger boy resulted and consequently he took a job with a local firm of auctioneers and estate agents. His pay was 15 shillings a week and he was required to collect rental from unfortunate people who could hardly spare the money. As his 18th birthday approached he was given the task of training an assistant, not realizing that it was his own replacement as his wage was about to rise to 22 shillings and 6 pence.

Finding himself unemployed Charlwood decided to take a holiday on the farm of a distant cousin: ‘Burnside’, near Nareen in the Western District. He travelled via Cape Otway, seeking the place where his grandmother and great-grandmother were shipwrecked in 1855 on the sailing ship ‘Schomberg.’ Charlwood found farm life enjoyable and was invited to stay on to help with the shearing and harvest of 1934. In fact he remained at ‘Burnside’ for the rest of the 1930’s; he was already writing and occasionally supplemented his wages by selling articles and short stories.

With the outbreak of war, Charlwood enlisted in the RAAF in 1940.After being placed on the reserve for eleven months he was posted to Somers, then to Canada to undertake training as a bomb aimer/navigator under the Empire Air Training Scheme. Six months, a number of courses and stations, and around 160 hours of flying time later, the initial training course was complete. While the training was arduous, Charlwood had the good fortune to meet a young primary school teacher named Nell East in Edmonton.

In England Charlwood was placed in a crew piloted by a West Australian named Geoff Maddern and, after completing an intensive training course, they were posted to No. 103 Squadron RAF, Elsham Wolds, in Lincolnshire. Shortly after their arrival the squadron converted from Halifaxes to Lancasters and Madden’s crew flew most of their tour of 30 operations in the latter type of aircraft in the winter of 1942-43.

On one of his first sorties, a mining operation in the Baltic, Charlwood’s aircraft was badly damaged by anti-aircraft fire over Denmark. As the pace of operations increased, Maddern and his crew attacked many major industrial cities including Turin, Munich, Essen, and Berlin. Opposition was intense, and on almost every occasion at least one crew from No. 103 Squadron failed to return. Over Wilhelmshaven a fighter attacked Maddern’s Lancaster and was beaten off by his gunners. A few nights later he and his crew met intense anti-aircraft fire over Bremen and the wireless operator was badly wounded.

March 1943 saw the start of the Battle of the Ruhr. With the aid of the newly-created Pathfinder Force, bombing accuracy improved, and Maddern flew to Essen, when his aircraft was again attacked by fighters, and to Berlin and Kiel. It was a period of very heavy losses and Maddern’s crew became the first of No. 103 Squadron in nine months to complete a tour of 30 operational sorties. On 7 April he and his crew flew their final operation with Duisburg as the target.

In his later writings Charlwood revealed that, of the 20 men who had qualified as navigators in his course, only 5 were alive at the end of the war. In two of his books, ‘No Moon Tonight’ and ‘Journey into Night’ Charlwood described his own experience and chronicled the fate of his friends. His vivid, moving records of these months are among the finest autobiographical works on Bomber Command and ‘No Moon Tonight’ has been compared favourably with ‘The Dam Busters’, the classic by another Australian writer, Paul Brickhill.

Another critic has compared Charlwood’s work with the enduring memories of World War 1 such as Remarque’s ‘All Quiet on the Western Front.’ The success of his other works notwithstanding, ‘No Moon Tonight’ remained Charlwood’s favourite as it was “a book of sorrow and companionship.” The extract quoted below reflects his response when, soon after his arrival at Elsham Wolds, two of his friends went missing.

With his tour complete, Charlton left England for the United States and training on Liberators, but back problems ended his flying career. Before returning to Australia he travelled to Edmonton and married Nell, the young teacher that he had met during his training. They were fortunate enough to be able to travel to Australia together.

After the war Charlwood worked for thirty years with the Department of Civil Aviation in Air Traffic Control, first at Melbourne Airport, then as a selector of men for ATC training; this was work that took him around Australia and New Guinea many times, and also to Britain, Canada, and New Zealand. His book ‘Takeoff to Touchdown’ is subtitled ‘The Story of Traffic Control’. Several of his aeronautical short stories appear in the collection ‘Flight and Time.’

During the post-war years Charlwood wrote eleven books. Two of these, ‘Marching as to War’ and ‘Journeys into Night’, were autobiographical and his collection of short stories ‘An Afternoon of Time’ is based on notes taken during his Nareen years. Proximity to the Shipwreck Coast during that time, plus the family connection with the loss of the ‘Schomberg’ in 1855, led to an interest in these events and ‘The Wreck of the Loch Ard’ and ‘Wrecks and Reputations’ were the result. ‘The Long Farewell’ was based primarily on diaries kept by emigrants on their lengthy and perilous journeys during the great European (Irish, English, Scots) waves of immigration that saw more than 980,000 settlers arrive in time to be counted in the Great Census of 1881.

However many readers of this magazine will have affectionate memories of Charlwood’s ‘All the Green Year’ which was a regular feature of the English curriculum at secondary school level for over two decades and was subsequently made into a popular television series. Set in 1929 in ‘Kananook’, ‘All the Green Year’ is a perceptive observation of Australian childhood of that era. It sold more than 100,000 copies and was republished in recent years as part of a series of Australian classics. Quite an achievement considering Charlwood’s grandfather could not speak English when he arrived in Australia!

Although ‘All the Green Year’ purports to be a novel, there is little doubt that the Charlie Reeve growing up in Kananook is the author recalling his school days in Frankston. Who could forget Charlie’s account of how he and his mate Squid ‘borrowed’ the camel from Perry Brothers circus and headed for the school? Squid ‘bailed out’, leaving Charlie to continue the journey into the school ground as depicted in the extract below.

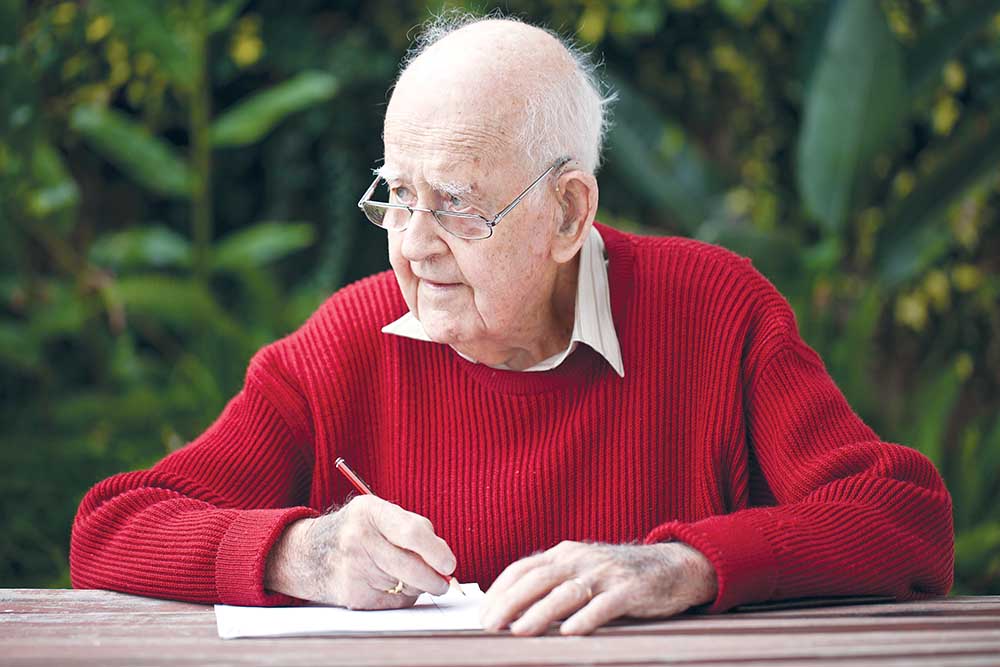

Don Charlwood became Vice President of the Victorian Branch of the Fellowship of Australian Writers in 1975 and held the position for fifteen years. He was awarded an OAM in 1992 in recognition of his service to literature. Don and Nell had four children (Jan, Sue, Doreen and James) and lived in Melbourne in their retirement. Don Charlwood died at Wantirna on 18 June 2012 at the age of 96.

For many years Charlwood had been an active advocate for a memorial to the 55,500 men who died in Bomber Command, and he asked a friend to represent him at the dedication by the Queen of the Bomber Command Memorial in London. Don Charlwood died ten days before the ceremony.

Footnote: The information included in the segment on John Cameron was contained in an article in the Newsletter of the Frankston Historical Society in 2012, and is printed with the Society’s permission.

Excerpt from “No Moon Tonight”

“I went to my bed, but before I reached it I saw that both Porter’s bed and Hardisty’s were empty. Opposite me Andy Stubbs was already awake, but silent.

“I went to my bed, but before I reached it I saw that both Porter’s bed and Hardisty’s were empty. Opposite me Andy Stubbs was already awake, but silent.

‘No word of them?’

He shook his head and lay staring at the ceiling. ‘Bull’ was awake too. The roar had gone from his voice. With determined indifference he said, ‘That’s the way it goes, son, that’s the way it goes.’

The girl’s photograph still stood over Porter’s bed, looking out with the same gentle eyes. Hardisty’s things were neatly arranged at the head of his bed….

As I stood there between the two beds, a feeling of desperation seized me. That we could go on like this was unthinkable. Someone must stop the whole insane business. Porter and Hardisty were dead! I went to the mess vaguely expecting rebelliousness or sadness or anger, but found only a mask of indifference and did not even recognise it as a mask….

By the time we had eaten tea it was dusk. I walked through the rain towards our hut, past the sports ground and the restless, disconsolate wood. The Halifaxes were starting up, filling the evening with wind-tossed roarings. Our hut was empty. When I reached its further end I saw that Porter’s and Hardisty’s kits were gone. Their beds were iron frames waiting for new tenants.”

Charlwood, Don “No Moon Tonight”, Crecy Publishing, Manchester, 2007 Pages 55-56.

Excerpt from “All The Green Year”

“Alone I looked down the main street. Already horses were rearing up and men were trying to quieten them. I huddled miserably behind the neck of the camel. Outside the Pier Hotel I saw old Charlie Rolls fall on his knees at the edge of the gutter and assume an attitude of prayer. Ahead of me, lining the centre of the road, were loaves of bread. The baker’s cart, with its door open, was travelling fast about a furlong in front of me. The camel advanced relentlessly, only pausing at Sam Yick’s to eat most of Sam’s display of Jonathans.

“Alone I looked down the main street. Already horses were rearing up and men were trying to quieten them. I huddled miserably behind the neck of the camel. Outside the Pier Hotel I saw old Charlie Rolls fall on his knees at the edge of the gutter and assume an attitude of prayer. Ahead of me, lining the centre of the road, were loaves of bread. The baker’s cart, with its door open, was travelling fast about a furlong in front of me. The camel advanced relentlessly, only pausing at Sam Yick’s to eat most of Sam’s display of Jonathans.

This journey through the town was one of the most depressing events of my childhood. Several tradespeople began pursuing us on foot, and the camel, by some fearful instinct, headed towards the school-in fact its last act was to eat the top off old Moloney’s liquidamber.

This brought everyone tumbling out of the classrooms, while behind me were the ranks of the tradespeople. There were cries of, “Mr Moloney, Charlie Reeve has come to school on a camel.”

Moloney burst out of his office and strode through the ranks, his face unbelievable.

“So you ride to school on a camel, Reeve? By heavens, when I’ve finished with you, you will stand in the stirrups for a week! Get off that animal immediately!”

My voice came from a long way off. “It kicks, sir.”

“So shall I – get off.”

I slid miserably to the ground. A murmur passed through the tradespeople. This heralded the arrival of my father from his office. I felt a moment of deepened shame, remembering his sleepless nights and the worry at home. I heard him exclaim, ”What’s the meaning of this?”

I waved my hand in the direction of the camel in a way intended to be explanatory.

My father said coldly, “Mr Moloney, I will leave him to you. I shall see him myself tonight.”

With that he turned and strode away, looking neither right nor left, as if he had been caught in the street in his underpants. I was frog-marched then through the ranks of spectators, Mr. Moloney breathing viciously in my ear.

So ended the affair of the camel-except that Squid had a week off from school after “a most unfortunate fall that quite upset him.” By this time my belief in justice was dead. “

Charlwood, Don “All the Green Year”, Pacific Books, 1969, Pages 51-52.