By Peter McCullough

When the “Great War” ended in 1918, Australia had a population of less than five million. During the previous four years about 500,000 Australians wore some type of uniform and few families were untouched by events in distant lands.

For 61,000 families, telegrams delivered the tragic news that a loved one had been lost. Some families had the misfortune to suffer bad news more than once: the Somers family of Mornington was one of those.

Dr J L Edgeworth Somers was a much-loved and highly respected doctor in Mornington in the late 19th and early 20th century. He died in 1938. Three of his sons enlisted during the First World War, but two never returned.

This story comes from records at the Australian War Memorial and the book ‘Our Boys at the Front’, published by the Mornington and District Historical Society.

SOMERS, Noel Travers Edgeworth

Enlisted 14/12/1914; killed in action 8/8/1915.

Noel was a 21-year-old bank clerk and stated on enlistment that he had prior service, namely “Cadet Royal Navy 2 years” and “3 years OIC Stonyhurst College”. He was in the 5th Reinforcements of the 14th Battalion, which left Melbourne on the Hororata on 17 April 1915, arriving at the Dardanelles on 9 July.

On 8 August he was reported missing at Gallipoli: was he killed or had he been captured by the Turks? It would be a year before the answer was known.

On 6 September 1915, Dr Somers wrote to the army enquiring as to “… the circumstances under which my son is posted as missing, and if you would give me your private opinion as to his chances of being alive and well though a prisoner, or to the greater likelihood of his being dead and not being discovered or identified. My boy had two chums named Friend and Greenwood (14th Battalion). Could I possibly have their relatives’ names and addresses so as through them to make some enquiries.”

The names and addresses were supplied.

In January 1916 the youngest son, Gervase Somers, wrote to the army stating that a list of prisoners captured by the Turks had been published in The Argus, but his brother’s name was not among them; was another list likely to appear?

Although the Anzacs left Gallipoli in December 1915, the fate of Noel Somers remained unknown.

Eventually a court of enquiry conducted by 4th Infantry Brigade AIF Headquarters sitting in Serapeum, Egypt, issued a determination on 7 July 1916.

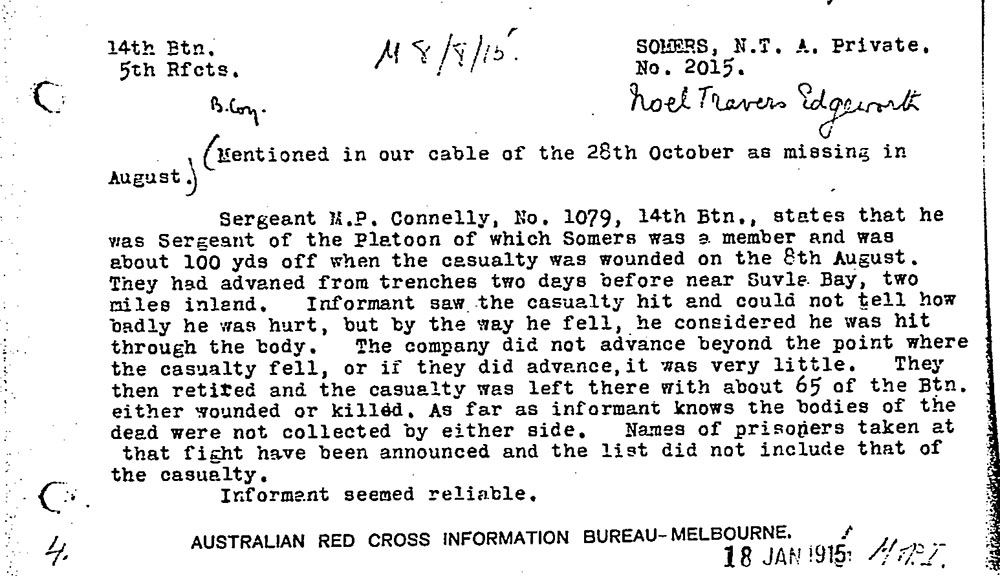

Although Noel Somers’s body was never found, the finding was based on a document submitted by the Australian Red Cross Information Bureau in Melbourne:

“Sgt M P Connelley, 1079, 14th Btn, states that he was Sgt of the platoon of which Somers was a member and was about 100 yards off when the casualty was wounded on the 8th August. They had advanced from trenches two days before near Suvla Bay, two miles inland. Informant saw the casualty hit and could not tell how badly he was hurt but by the way he fell he considered that he was hit through the body. The coy. did not advance beyond the point where the casualty fell, or if they did advance, it was very little. They then retired and the casualty was left there with about 65 of the Btn. either wounded or killed. As far as informant knows the bodies of the dead were not collected by either side. Names of prisoners taken at that fight have been announced and the list did not include that of the casualty. Informant seemed reliable.”

By 29 September, Dr Somers had received a package containing his son’s effects: postcards, hairbrush and letters. Over the next few years he received Noel’s medals, the memorial scroll and memorial plaque.

Sometimes the official records throw up a piece of information that leaves the reader guessing.

Noel Somers stated in his enlistment papers that he was not married and listed his father as next of kin. When Dr Somers wrote on 6 September 1915 asking for the home addresses of Noel’s chums, Dr Somers concluded his letter: “It is Mrs Somers special wish that the news of whatever kind when it comes should be communicated direct to me and not through the medium of another person.”

However three days earlier (3 September 1915) the Officer Commanding of the Australian Records Section of the AIF in Alexandria received the following instruction:

“In the event of any casualty to No. 2015 Private N T E Somers, 14th Battalion, will you please notify his wife, Sister Somers, Military Hospital, Grand Hotel, Helouan.”

All of his effects, medals, etc were sent to his father as next of kin.

Also, while service records of other soldiers contain a very basic will, this was missing from the file of Noel Somers.

SOMERS, Gervase Louis Edgeworth

Enlisted 16/5/1917; killed in action 12/10/1918.

An 18-year-old student, Gervase had to get permission from his parents to enlist as he was not 21.

He, too, claimed experience in the Sea Cadets (two years) and he was posted as part of the 9th Reinforcements for 60th Battalion.

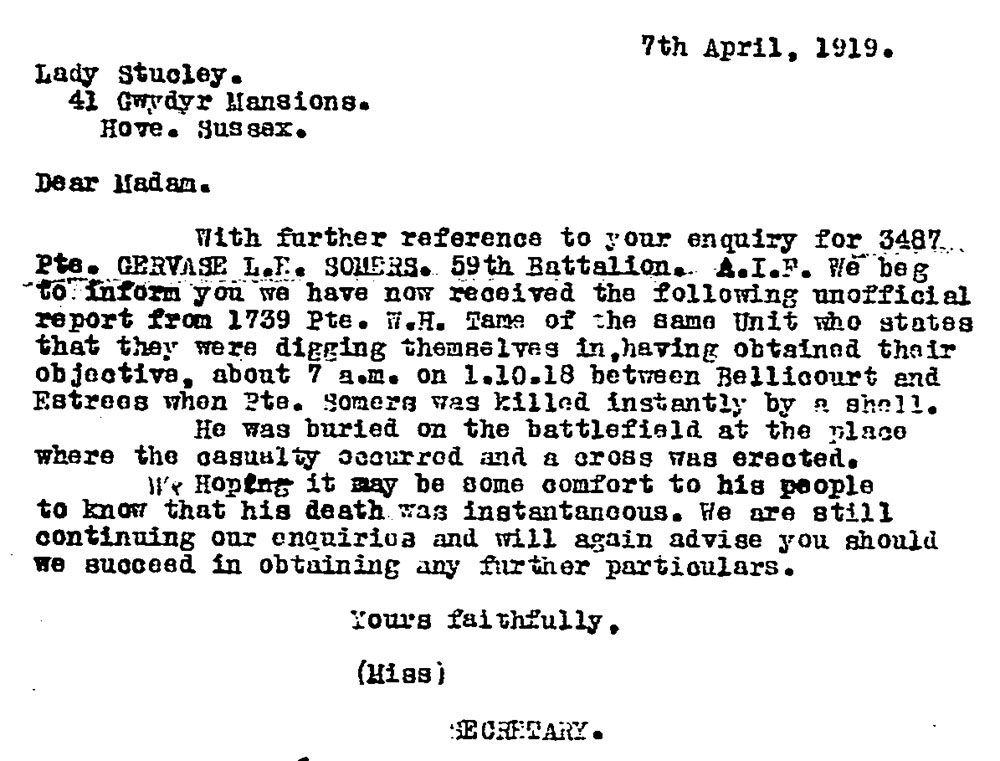

It was May 1918 before he arrived in France and where he transferred to the 59th Battalion. After a spell in hospital with influenza and attending the Australian Corps School, he was selected to go to England for an infantry cadet course in October 1918.

Sadly he was killed before departing and was buried in the Prospect Hill Cemetery, near St Quentin in France.

By May 1919 Dr Somers was signing for a package of personal effects: address book, leather cigarette case, leather card case, notebook, paper knife, silver spoon, wallet, cards, and photos.

In July a separate package arrived with a pocket book, and then came medals and the memorial scroll and plaque.

Photographs of the grave were also supplied.

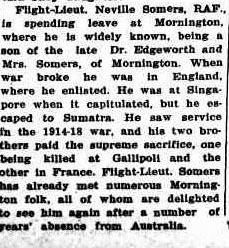

SOMERS, Neville Edgeworth

Enlisted 26/1/1917: discharged 25/3/1919.

A 21-year-old medical student, Neville claimed four years in the Sea Cadets as relevant experience. After training at No. 5 Australian General Hospital he embarked on 10 May 1917, reaching Suez on 20 June.

Originally allocated to the Camel Field Ambulance, he was considered surplus to requirements and transferred to the 1st Light Horse Ambulance and saw out the war in Palestine.

Like many others in that campaign, Neville did not escape the scourge of malaria. The Peninsula Post of 31 January 1919 tells of an incident he experienced earlier. It reported: “Some months ago a horse he was riding was killed by a shell which burst nearby, and although Trooper Somers narrowly escaped death, he suffered severely from shock for some time and has since been in hospital with malaria for two months.”

This incident may be the explanation for his misdemeanour on 3 February when he was fined for “offensive language to an NCO”.

Trooper Somers embarked for Australia on 26 January 1919 and was discharged on 25 March with the intention of resuming his university studies.

Did Neville Somers complete his medical studies? His service record gives no indication.

The next document on his file, after his discharge papers, was a letter written in 1945 to the Officer-in-Charge, AIF Base Records in Canberra, requesting a copy of his statement of service.

By now he was using his full name, “Neville Essex Edgeworth de Firmont Somers”. It is understandable that it was not revealed to the boys in the Camel Corps or in the Light Horse.

Neville’s letter requesting a copy of his statement of service explained politely and in some detail that while serving as an RAF officer in Singapore in 1942, he had to depart in something of a hurry. His personal papers and other effects were to follow by sea, but he never saw them again. He even enclosed a stamp in case the army was short of petty cash.

The letter, containing all the details, was not acceptable to the army; “Trooper Somers”, as he was referred to, was required to fill out the detailed statuary declaration to which was attached a form with a number of questions. Even then there was no guarantee of a favourable response; only “… further consideration will be given to the matter”.

Although the covering page contained all the necessary detail, the army asked Neville to “… detail the circumstances under which the papers were lost”.

Probably mouthing a few of the words that got him into so much trouble in Palestine in 1918, the old trooper wrote “Act of God”.

Even the army baulked at the thought of questioning the act of the Supreme Being, and the request was acceded to.

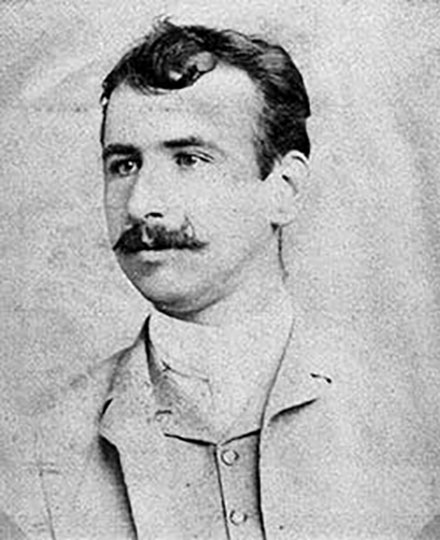

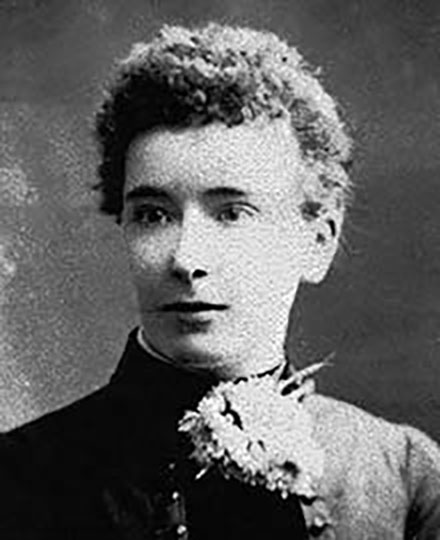

Dr James Louis Edgeworth Somers and Frances Mabel Edgeworth Somers.

The Heartbroken Somers Parents

Dr James Louis Edgeworth Somers

The father of the three soldiers was a larger–than–life character in Mornington and the wider peninsula community for many years.

In ‘The Bush – A story of the Mornington Bush Nursing Hospital’ by Hilary Abeyaratne, we are given an insight into his contribution:

“’Pioneer practitioner’ was the term used by The Peninsula Post to describe Dr J L Edgworth Somers when he was, on account of his long and meritorious service in the area, given the honour of addressing the gathering at the opening of the hospital in 1937. In practice on the peninsula since 1892, one of its best known and respected citizens, Dr Somers was still amazingly fit at 75 when he died most suddenly and unexpectedly, ‘a grand old gentleman and an ornament to the medical profession’.

He was loved as a doctor given to great skill in diagnosis, and also highly respected as the chairman of the local justices. In fact, the day before he died he presided over the cases listed at the local police court for the morning, did one set of his medical rounds soon after, another in the afternoon and again one that night, apparently in perfect health.

He is also remembered for the white horse on which he made his calls (although he later owned both a motorcycle and a car) and for the pack of noisy dogs that accompanied them to herald his arrival.

Dr Somers’s story before coming to Mornington is ‘most remarkable and romantic’. The son of a doctor in Ireland, he was, at 19, the youngest at that time in the British Empire to obtain his BA (Cantab) before going on for his clinical studies at St Mary’s Hospital, London.

In the years between his graduation and his coming to Mornington at the age of 30, he had had a most adventurous life. He was serving as a surgeon at Fort Juby in West Africa when he was attacked and badly wounded by marauders; he was rescued by a friendly Arab tribe with whom he remained for the next couple of years, living as an Arab.

Later, he lived and practised in South America and Spain before coming to Australia in 1890 where he first toured Queensland on foot before coming to Victoria and Mornington.

He served the town for 45 years, never missing his daily swim at the baths, in winter or summer, until a couple of years before he died in his sleep at his home, Tarfayah, in Albert Street on 17 February 1938.

Shortly after his death the citizens of Mornington erected a cairn and sundial. It was dedicated on 16 July 1939 by Sir George Fairbairn and the inscription reads: ‘This sundial is set here in memory of a beloved physician, James Louis Edgeworth Somers, who ministered to the sick of the Mornington Peninsula from 1893 to 1938’.”

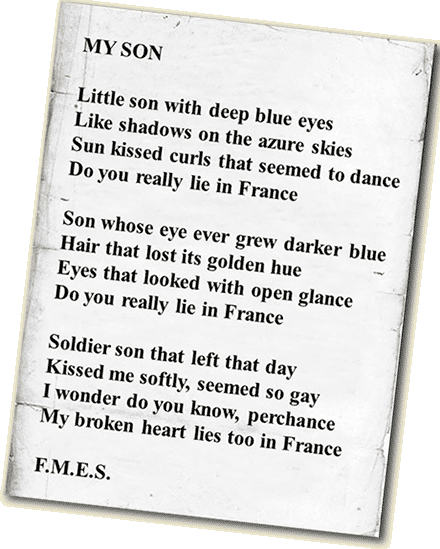

The poems that were published in the Peninsula Post.

Frances Mabel Edgeworth Somers

Mrs Somers was the daughter of Dr Joseph P Usher of Ballarat and a cousin of Dr Somers. Apart from three boys, the family also included two girls: Florence Ruth Mary Edgeworth Somers and Monica Mary Patricia Edgeworth Somers.

Mrs Somers shared the “intense anxiety” that Dr Somers referred to in one of his letters to the AIF when they were waiting on news of Noel.

On 15 June 1917, The Peninsula Post wrote in its editorial that “The memory of Pte. Somers is kept alive in St Macartan’s Church by two beautiful silver vases, suitably inscribed, presented by Mrs Somers …”.

In a letter to The Post in November, 1917, Mrs Somers said she was to make a presentation to the Shire of Mornington of a memorial board of the fallen of the district, as a “small personal gift”, and expressed the hope that a more enduring marble memorial would be erected after the war to which she would contribute.

On 22 December the memorial board was officially presented by Mrs Somers before “a large assemblage of relatives and friends”.

It was described as “beautifully carved by an English artist (a brother of an Imperial Officer) …” and bearing the names of 20 boys from the district.

It was unveiled with great ceremony by His Excellency Sir John Maddern, Lt Governor, whose stirring speech was reported in The Post on 4 January 1918:

“The noblest feelings of humanity which are theirs, adorned their character and their sacrifice, and so our grief was assuaged in the pride of their heroic deeds.”

Sadly, more grief lay ahead for the Somers family with the death of Gervase toward the end of the war. His name was added to the board, which can be viewed at the Mornington RSL, beside that of his brother.

The grief of Mrs Somers was made more tangible by poems she wrote which were published in The Post after the war.

Our Boys at the Front: 1914-18 The Mornington Peninsula at war from the pages of the Peninsula Post is an excellent resource for anyone interested in this period of history. It includes a DVD.

Peninsula Essence – April 2021