The first time I see Kenny Brunner, he is walking out of the Breakers’ basketball stadium in Mornington. He is surrounded by a sea of kids, all “high-fiving” him as they parade through. Kenny is loving it and wears a grin from ear to ear. It goes without saying that in these parts, among the basketball fraternity, he is a celebrity.

US expat Kenny Brunner is the director of coaching and head coach of the senior men’s program for the Western Port Steelers and fills much of his time running coaching clinics and workshops for kids through to young adults.

But how did he end up in our beautiful part of the world on the Mornington Peninsula? Well, it’s a story about trouble finding Kenny, jail time awaiting trial and ultimately redemption after he turned his life around.

Despite having a rocky start in life, Kenny Brunner was destined for big things. Born in Los Angeles, he was raised mostly by his grandmother with help from his aunts.

“My parents weren’t around. My mother was a drug addict and my father was an alcoholic, so it was up to my grandmother, Mary White, to raise me.”

In fact, his parents only saw him play twice in his 137 games.

“A mother teaches you to love. A mother teaches you to value women. A mother is supposed to help and support you,” said Kenny. “I never got that from my mother. I got that from my grandmother.”

And raise him she did. In fact, she was the one who first put a basketball in young Kenny’s hands.

“Initially, I was a football player. It was my grandmother and aunties who encouraged me to take up basketball.”

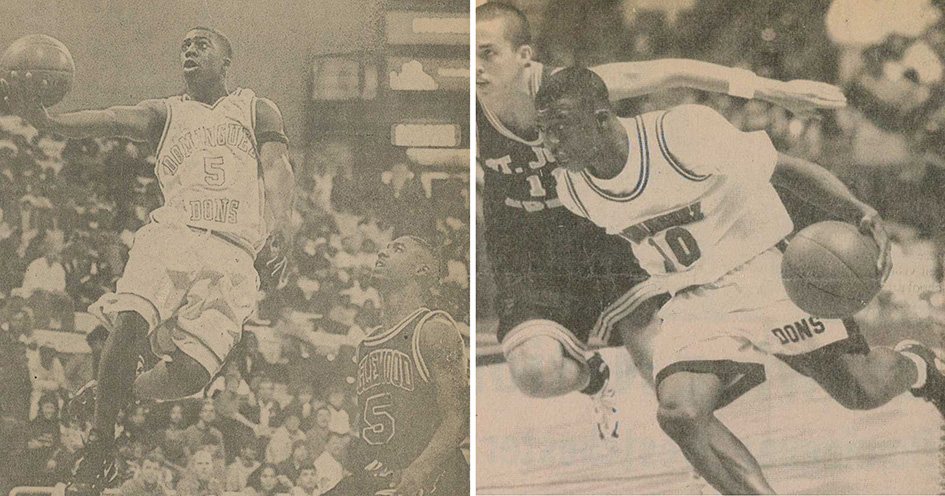

Once that basketball hit his hands, he knew he was onto something. And by age thirteen, it was believed Kenny was headed for greatness.

To help him in his development, the decision was made to send Kenny to school in Compton, which was an hour-long bus ride each way from home.

“Compton was a rough place. It’s a Crips’ neighbourhood, whereas Inglewood where I was from was a Bloods’ neighbourhood,” said Kenny, referring to the infamous red versus blue-wearing gang rivalry that is still synonymous with violence today.

“But, you know… I’ve never been fearful of people. I will go anywhere and wear whatever colour I want.”

Kenny fast got a reputation playing streetball in Compton; a showy form of the game, it was serious business back then for those on the road to the big time.

“It was a good way to get noticed. Although these days, it is more about tricks and entertainment.”

And Kenny ended up being noticed. As a teen he was considered the number one point guard in the country.

Kenny enrolled at Georgetown University in Washington DC in 1997.

After Georgetown, Kenny moved to California State University in Fresno, back closer to home. But trouble was not far away. He was charged after allegedly assaulting another student with a samurai sword, and suspended indefinitely from the team before playing a single game.

“I was there, but it was more guilt by association,” said Kenny.

The judge dismissed the charges against Kenny saying: “I think this started out as a bunch of horsing around … and it got out of hand.”

For Kenny, he was just happy to have the whole saga behind him and get back to what he loved; playing basketball.

But things did not go smoothly. Back in Compton, he landed himself in more hot water.

In May 1998, Kenny was arrested on suspicion of armed robbery. It was alleged he had held up Los Angeles City College basketball Coach Mike Miller at gunpoint inside the school’s gymnasium, robbing him of about US$1,500.

Thus began Kenny’s darkest time. He spent four months in the LA County Jail awaiting a trial that could see him imprisoned for a long time.

Jail was a very tough place. A place with an abundance of violence and shortage of hope. Kenny looked for hope elsewhere and it was in jail where he developed a strong faith in God.

“I knew I needed help. I needed love. In those dark times, God, and his plan for me was an enduring comfort”.

Just two days before the trial, Kenny was cleared of all charges.

“I was never there,” said Kenny. “They wanted to know who was there, but it wasn’t my place to say. I had nothing to do with it.”

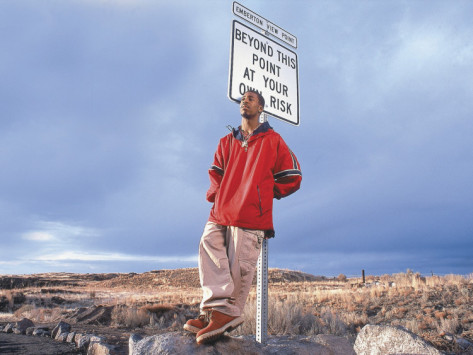

College of Southern Idaho was the next stop for Kenny. A town called Twin Falls, famous for where Evil Knievel held his failed attempt to jump the Snake River Canyon in the rocket-powered “Skycycle X-2”.

It was also one of the whitest areas in America with just half of one percent of the population being African American.

Here Kenny fell under the stewardship of Derek Zeck, a “pull no punches” coach who laid it all on the line for Kenny.

“I have never been treated worse in my life, than I was under coach Zeck,” said Kenny. “But he was without a doubt the best coach I ever had.”

Push, push, push was Zeck’s motto, and there was hardly a practice where Kenny wasn’t kicked out for not trying hard enough.

“It was a daily routine. Kicked out of practice and made to come back and run five miles at 6am the next morning.”

It wasn’t just the coach that was tough on him. In this predominately white part of the United States, the crowds from the opposing team often gave Kenny hell.

“I remember one game against Utah Valley. It was the worst racism I ever had to deal with. The crowd were brandishing Samurai swords, and the ‘N’ word was bandied about. That was a low point.”

Kenny was motivated to succeed though. He wanted to make his grandmother proud. He wanted to show his coach, his team and all the doubters that he had what it took to go all the way.

And his hard work was paying off. In fact, Sports Illustrated journalist Grant Wahl had come to town to do a story on Kenny’s rise against adversity, and his plans to enter the draft. The reports were glowing from the coaches and school staff. Everything seemed fine. Then, later that day came the bombshell from Coach Zeck that Kenny had been suspended indefinitely.

“Coach Zeck was mad at the whole team,” said Kenny. “He told us all to leave and to come back at 10pm. I was like ‘I’m not coming back. I’ll see you at 6am’.”

It was coach Zeck’s anniversary, and Kenny took it upon himself to make sure that his coach celebrated it. Kenny and a few teammates headed to the movies, but the coach sensed a mutiny.

It wasn’t until the next day that Kenny was told the bad news. As the perceived leader of the rebellion, he was out.

“Clean your stuff out – you’re done,” he was told.

Kenny’s latest fall from grace attracted attention. Sports Illustrated magazine ran a story describing Kenny, sitting in the passenger seat of a pick-up truck in the parking lot of a convenience store, ringing his beloved grandmother, and sobbing down the phone: “Granny, I’ve got some bad news…”.

Coach Zeck decided to take Kenny back. As bad as his actions had been to Zeck, he knew he needed the young point guard on his team. Kenny played out the season.

Time was ticking for Kenny to achieve his dream on playing NBA basketball. At the end of the season, Kenny headed to the University of Georgia for a year, but was not cleared to play. This failure was to become the defining fork in the road; the moment Kenny’s dream to play in the NBA slipped through his fingers.

Kenny headed home and out of the junior college system to play in the American Basketball Association competition, a semi-professional league.

“I was the highest paid point guard in the league in 2001,” said Kenny.

His results speak for themselves, with Kenny averaging 16 points, 6 assists, 4 rebounds and 2 steals per game.

Again, his career hit a hurdle when he broke his leg and injured his knee.

After recovering, he delved into the world of “exhibition” basketball, where he could show off the “street-ball style” he had grown up playing.

He went on the “AND1 Mixed Tape” tour in 2003 and 2004. The “AND1 Mixed Tape Tour” was a traveling basketball competition and exhibition presented by B-Ball and Company and the basketball apparel manufacturer AND1. Kenny and travelled through Europe and Asia playing the entertaining, streetball brand of basketball. He also played competitive basketball in Europe, the United States and Mexico

The crowds loved him. He had the moves and the reputation as a bad boy of the game.

“Bad Santa” they called him. Or “The Bad One”. He loved the attention and worked on marketing himself. He had a shoe made in his image, and had plans to market the Kenny Brunner brand.

Fate would intervene in 2009 when Kenny received a call from Australian basketball coach Ryan Rogers.

“I was playing in Mexico at the time,” said Kenny. “The phone rang and Ryan said ‘how about coming to Australia to play?’”. It was an opportunity too good to refuse.

Kenny headed to Kalamunda in Western Australia where he began to settle in and get his rhythm.

“I was averaging about 16 points and six assists, and getting my confidence up. One game, a guy came up from under me and tore my ligament from my bone.”

It was another blow for Kenny; the man who had been through more trials than most could imagine.

It is telling that Kenny has Psalms 13 tattooed on his forearm: “How long wilt thou forget me, O Lord?”, it begins. “How long wilt thou hide thy face from me?”

Luckily for Kenny, salvation arrived. Not as a light from heaven, but in the arrival of his first child.

“My baby changed my view on coaching. It hadn’t appealed in the past, but I discovered I had so much to give, and that is what I wanted to do,” said Kenny.

Two more children followed and a recruitment to become the coach at the Western Port Steelers in 2012.

“I had found my place,” said Kenny.

Kenny coached the Steelers until 2013 when he returned to Adelaide to be closer to his partner’s family, but found himself back in 2015.

“The first year I came back, we made the grand final. The second year back, we won it!”

Kenny’s life is one dedicated to promoting basketball, and fostering talent particularly among the young.

Perhaps it is his own three boys that have taught him the value of youth. Or perhaps it was the grandmother who never gave up on him that has burnt the value into his psyche.

“She has passed on now, as has my father,” said Kenny. “My aunty Karen and my cousins Brian and Brandon are still in the United States, and going strong!”

When Kenny isn’t working his role as the director of coaching for the Western Port Steelers, he can usually be found at a local school running basketball programs.

He runs coaching clinics at Penbank School (where he coaches all six of the school’s teams), Somerville Primary, Pearcedale Primary, Tyabb Primary and Mount Martha Primary. He also runs the Point Guard Academy for promising up and coming players.

“I am happy to be where I am,” said Kenny. “I work seven days a week doing this, and I absolutely love it.

“My faith has taught me that everything happens for a reason. Everything that has happened was supposed to happen.

“I have been able to give back so much to others; especially kids. My heart is with the kids; I want to help them so they don’t have to learn life’s lessons in the same way I had to.”

“I love my kids so much,” said Kenny. “My oldest boy is already shooting a ten-foot rim! I think he will be a baller”.

Kenny has found himself in a lovely part of the world, and when he gets a few hours off, heads to the beach to unwind. But does he regret not making the ‘big time’?

“I achieved my aims,” said Kenny. “I was the ‘Skip To My Lou’ of the East coast (a reference to famous West Coast streetballer Rafer ‘Skip To My Lou’ Alston), I had my own shoe, and I was the number one point guard in the country.”

In fact, Kenny is confident in his legacy, and won’t let anybody forget it.

“I am the best streetballer that has ever laced up shoes.”

It seems fitting that this man, whose life has been through many trials, has that Psalm 13 tattoo etched on his skin.

The tattoo graces his forearm, and begins with a message of being forsaken but ends with the earning of redemption:

“But I have trusted in thy mercy; my heart shall rejoice in thy salvation. I will sing unto the LORD, because he hath dealt bountifully with me.”