By Lance Hodgins

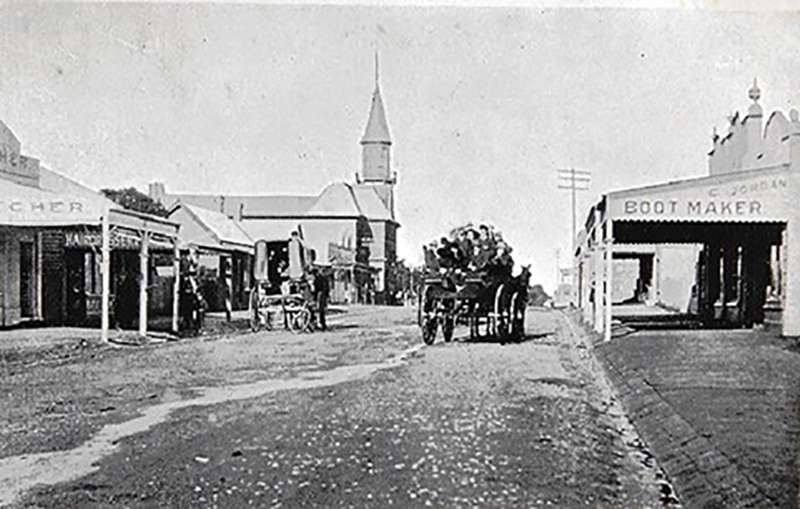

Horse racing was one of the earliest organised sports on the Mornington Peninsula. The first Mornington races were held in the 1870’s on part of Beleura, a property which at that time stretched to Sunnyside Creek. The Mornington Racing Club grew out of the Baxter’s Flat race meetings and conducted its first meeting in 1899.

Early horse racing at Mornington

In 1911 the Mornington Racing Club began leasing its current site on the Drywood Estate. It registered with the Victorian Racing Club and soon after World War 1 the first Mornington Cup was held. Racing boomed through the 1920s and 30s and Mornington drew praise as one of the best courses outside Melbourne.

During World War Two this fine course was used as a signals training depot by the army. The racetrack was dotted with telegraph poles, the race buildings were neglected and the surroundings became overgrown.

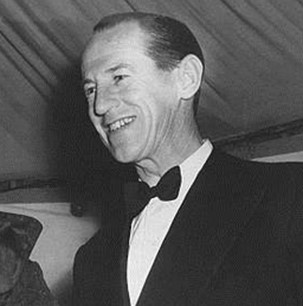

Reginald Ansett to the rescue

In 1947 Reginald Ansett, a Mt Eliza resident, formed a company which bought the course and set about restoring it to its former glory.

Ansett was one of Australia’s most successful businessmen. His home-grown airline company had gone into wartime production employing 2,000 workers. After the war Ansett Transport Industries established cut-price interstate flights and linked them to his own resort hotels across the country.

Ansett’s toughness and enthusiasm were admirably suited to the struggles which faced the Mornington Racing Club. He arranged to purchase the land for £14,000 and set about restoring it, filling in the holes in the track and removing the scrub from the surrounds. His business acumen led him to buy the army buildings, useful at a time when building materials were in short supply.

Twelve months later, on Thursday 4 December 1947, the re-birthed Mornington Racing Club held its first meeting in front of a record crowd of 6,500 spectators. Full of enthusiasm, the Club undertook a two-year program of expensive innovation and additions, including the enlarging of the members’ reserve.

A problem emerges

Early in 1949, however, rumours began to circulate that the trainers were about to boycott the Mornington Cup meeting. On the night before entries closed only 26 horses had been nominated for the entire meeting and Club Secretary Jack Cuddigan was getting worried.

The action had been suggested at a meeting of the Victorian Trainers’ Association but it was obvious that many trainers were not in attendance and the VTA was reluctant to say whether the race meeting was officially “blacklisted”. There were, however, rumours that pickets had been posted outside the city office of the Racing Agencies to discourage entries.

The main grievance was over the issue of tickets to trainers. Across the State, it was the practice for all members of the Victorian Trainers’ Association, whether they were racing at that meeting or not, to be admitted free of charge – to not only the race course but also to the members’ enclosure.

Trainers claimed that only the members’ enclosure gave them a good view of the finish in the likelihood of needing to make a protest. This was certainly true of the Mornington track, where the trainers’ area was off to one side of the finish line.

The Mornington Racing Club felt that this was going too far. Their Club had 680 members and each one was given two ladies’ tickets; the members’ enclosure was unable to handle more than 1,500 people. Mornington argued that all of the 260 members of the VTA did not deserve free entry into every race course, let alone into a potentially overcrowded members’ enclosure.

In a last-minute gesture, the Victorian Racing Club tried to ease the problem by “recognising” VTA membership but the Mornington Club dug in its heels. It decided to go it alone with a compromise: it would allow all trainers entry into the racecourse but NOT into the members’ enclosure. Ansett was not convinced that all trainers were “men of standing” and “worthy of membership”.

When nominations closed on the following day, entries had swelled to 80 and it looked like the Cup meeting would go ahead as scheduled for 24 February. The VTA responded by officially announcing a boycott.

Mornington fought back by asserting its right to control its own members’ enclosure.

Said Ansett: “My committee is unanimous that they are the ones who control the Members’ Reserve and therefore they are not prepared to automatically admit trainers to it.”

Ansett then asked the VTA to lift its embargo for such an important meeting, but they replied that it was now too late and they had the support of 90% of their members.

Twenty of the nominated horses, however, had come from just three VTA members and it appeared that there might be a rift in the trainer ranks. Within days Victoria’s leading trainer, Fred Hoysted, announced his intention to resign from the VTA. Hoysted stated that he had never been associated with a dispute or a strike in his long training career and he didn’t intend to start now.

The boycott by trainers looked like it might widen to embrace bookmakers, transporters and jockeys. Already at least one owner was told by a jockey that he would not take his ride for fear of being seen as a strike-breaker and suffer further recriminations.

Nevertheless, the 1949 Mornington Cup meeting came and went. It was a great success with over 7,000 spectators and of the sixty-four acceptances only fifteen were withdrawn. Trainer Des McCormack resigned from the VTA and had ten horses competing. Fred Hoysted had a good day: he also left the VTA, provided seven runners, and won the last event.

In presenting the Cup to the winning owner, the Chief Secretary referred to the “frivolous” dispute between the Club and the Trainers’ Association. A few days later, support for Mornington came from the VRC which slammed the trainers for using boycott methods to ventilate their racing grievances.

A compromise that pleases nobody

Unfortunately, the deadlock continued and the VTA warned that their members would not be entering horses in the next Mornington meeting coming up in four weeks time.

The Chairman of the VRC hastily spoke to the Trainers’ Association, and then held an informal meeting with Mornington to reach a compromise: those trainers who also held a VRC badge would be admitted to the members’ enclosure as well as the trainers of horses competing on the day. The boycott of the 21 March meeting was lifted and the meeting was saved.

The VTA, however, were still not happy. They felt that Mornington had driven a wedge into their ranks and created two classes of trainers: the “haves” and the “have nots”. They also feared that the Mornington “disease” would spread to other racing clubs throughout the State.

Mornington maintained that they were not being vindictive towards trainers in general. After all, they had already reduced training fees at their track from £1 to 10 shillings for a gallop on the rails and 5 shillings on the outside of the track.

But on the matter of the trainers and members, Ansett and his Club remained firm: Mornington would simply not admit all of the trainers to its members’ reserve.

The problem simmers

The situation remained static for three years – until April 1952 when it boiled over again. The VTA’s patience ran out and it indicated that it might boycott the 3 May meeting over the Mornington issue.

With only 30 horses nominated for the six events, the Mornington Club was forced to extend its closing date. When the VTA officially announced a boycott, seventeen of those horses were withdrawn leaving most of those remaining from small trainers who were not members of the Association.

The principal race of the day – the Dava Handicap – had only three horses entered, one of which, ironically, belonged to Reg Ansett himself. A week out, the Mornington Racing Club was forced to pull the pin and cancel the meeting.

Nonetheless, Mornington stuck to its guns. It pointed out that it had spent a whopping £20,000 on improvements – one of which was a trainers’ stand – but it still could not accommodate all trainers in its members’ enclosure.

The stand-off continued. On Mornington’s request, the VRC were called in to act as a mediator, a role rejected years earlier by them on the grounds that this would be “interfering in a domestic matter”. This time around, however, it was the trainers who refused to come to the table, and so the deadlock intensified.

The VTA even rejected an approach by the Owners’ Association and maintained that they would talk only to the Mornington Racing Club.

“This is a matter between the trainers and the Mornington Racing Club and we have no intention of meeting the VRC or any other body. We demand equal rights for trainers, and until we come to an agreement with Mornington no one can make us nominate horses for any of that club’s meetings.”

Mornington’s Reginald Ansett reply was stern.

“We are sick and tired of the whole thing and we could just as soon close down the racecourse and sell it. We could let the polo people or anyone else interested have Mornington Racecourse and get out of it nicely.

“I know it’s a tragedy to speak this way, but we can’t be pushed around. Mornington members feel that they should have control of their own members’ enclosure. If they don’t, it’s not worth going on.

“We are all heartily sick of the argument.”

Ansett pointed out that the cancellation of another race meeting would hit hard and wide.

“There were likely to be staff dismissals,” he went on, “as well as a loss of revenue for the government, charities, owners, jockeys and the trainers themselves.

“Trainers claim that they put on the show but they forget that without owners to foot the bill, jockeys, and the paying public, there would be no racing.”

Only 18 entries were received for 31 May race meeting and it was reluctantly called off. Ansett’s forecast of a widespread effect was proven right, as the day was to be in aid of four local charities: two Catholic parish schools, the Menzies Boys Home and the Andrew Kerr Memorial Home. Furthermore, in order to achieve a profit for these good causes, prize money had been kept to a minimum – which now drew complaints from the Owners’ Association. Ansett took the opportunity to accuse them of being in cahoots with the trainers and being dictated to by the VTA.

The Victorian Racing Club finally steps in

The VRC had finally had enough. They ordered both the Mornington Club and the Trainers’ Association to forward submissions for consideration at their next committee meeting on 30 May 1952. This would require a back-down from the trainers who had always demanded that they thrash things out only with the Mornington Club and no-one else. They complied with the request.

After the meeting, the VRC Committee issued the following statement:

“The Committee emphasises that every racing club has an obligation to provide accommodation for both its members and the public, and that each club has an essential right to control admission to its own members’ enclosure without direction from the Victorian Racing Club or any subordinate organisation.”

And then came the crunch.

“The main fact is that there has been an admitted and long sustained boycott of a Club (Mornington) by an organisation (VTA) established primarily for advancing the interest of its own members and determined to enhance its own status by enforcing privileges for them.

“In the Committee’s opinion, the action of the VTA was not justified, and in future the VRC will not recognise the VTA or deal with it or its representatives on any racing matter so long as the Association supports a policy of direct action.

“Production of the VTA badge will no longer entitle the holder to any privileges at Flemington.”

Towards a resolution

This withdrawal of long-held City privileges by the VRC hit the trainers hard. One third (119) of VTA members had VRC badges as well and so the ban would not affect them. For the remaining two-thirds of the rank and file VTA members, however, this ban was like a red rag to a bull. They were determined to fight. What if other country race clubs decided to follow Mornington’s example?

A general meeting of the VTA chose to challenge the power of the VRC and decided that it would continue to boycott races at Mornington. But there were signs of alternative opinions in the ranks, and the next Mornington fixture was not scheduled until October – which would allow plenty of time to consider all options.

At the next general meeting of the VTA some members felt that they were pursuing a hopeless cause in defying the VRC, which now did not recognise their badge at all. Metropolitan clubs were refusing to allow VTA members to run trials on their courses, which was a major problem as fees from these trials and the sale of race books made up a large part of the VTA’s revenue. Furthermore there were more restrictions being imposed at Flemington involving admittance to the birdcage, access to the trainers’ stand, and use of the trainers’ car park.

The dispute finally collapsed on Thursday 24 July 1952.

After a lively discussion, members of the VTA accepted Mornington’s offer to allow only trainers of competing horses access to the members’ enclosure, and the trainers immediately applied to the VRC to have all of their Flemington privileges restored.

A happy future

With the issue resolved, development of the racecourse and its surroundings grew rapidly.

Today, the race course is very much part of the Mornington suburban area. In 2010, the Melbourne Racing Club merged with the Mornington Club, and it is now home to monthly race meets and much loved annual events. It has frequently been voted the best “country” track in the State.Still occupying its original 68 hectare site, it is a popular venue for staff functions, car displays, farmers’ markets and rock concerts.

And, of course, its member facilities are second to none.

This is a chapter from “Tiffs Over Time”: a collection of arguments from earlier times on the Mornington Peninsula. Copies are available from the author, Lance Hodgins, for $20 plus postage (if necessary). Ring Lance on 5979 2576.